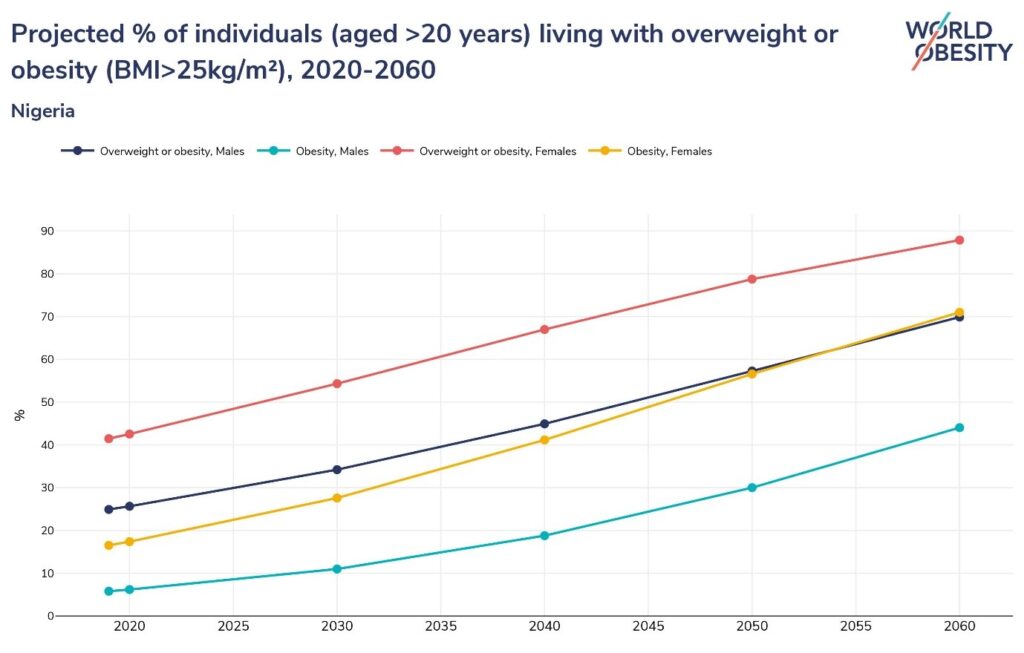

Obesity is on the rise globally, with 1 billion people predicted will be living with the disease by 2030. Obesity is no longer just a disease of rich countries. The incidence of the disease is now more pronounced in lower and middle-income countries, especially in poorer and more vulnerable communities. Evidence from recent systematic review and meta-analysis shows that as at 2020, there were more than 21 million overweight and 12 million obese ‘persons in the Nigerian population aged 15 years or more, accounting for an age-adjusted prevalence of about 20 percent and 12 percent respectively’. Figure 1 below further shows clearly that the number of people living with obesity (BMI>25kg/m²) in Nigeria is rising steadily. The causal factors for increased body mass index (BMI) include eating patterns, physical activity levels, and sleep routines

The World Obesity Federation (WOF) also shows that the Nigeria has a high national obesity risk with a score of 7.5/10. The WOF also shows that Nigeria’s chance of meeting the UN adult obesity targets for 2025 is very poor (sadly 0%) for both men and women. Failing to meet the obesity target jeopardizes other NCD targets, including the World Health Organization’s target of a 25% reduction of premature deaths from several leading non-communicable diseases by 2025.

People living with obesity may be at a greater risk of other chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, many types of cancers, and premature death. Obesity increases the risk of certain mental disorders such as depression. The disease is also associated with cognitive decline, enhanced vulnerability to brain impairment and accelerate age-related diseases of the nervous system. Moreover, childhood obesity can severely affect children’s physical health, social, and emotional wellbeing, academic performance and self-esteem. Obese children also more likely to experience respiratory problems such as asthma, sleep disorders such as difficulty breathing while asleep (sleep apnea), high blood pressure and elevated blood cholesterol. …..

Obesity has significant impact on the Nigeria economy. Data from the global obesity observatory shows that in 2019, the economic impact of overweight and obesity in Nigeria was estimated to be over N1 trillion (US$2.37 billion). This is equivalent to US$12 per capita and 0.5% of GDP. Direct costs and indirect costs made up 20.2% and 79.8% of total costs respectively. By 2060, the cost implication of obesity, including healthcare and reduced productivity, among others, will amount to over US$35.38 billion. Without urgent intervention, the continuing increase in adult and childhood obesity will overwhelm the already precarious health care system of Nigeria and increase the high risk of lost productivity in the Nigerian economy. Therefore, the need for substantial policy interventions to prevent the rise of obesity in the nation cannot be overemphasized.

Currently, Nigeria’s health policies, interventions and actions aimed at reducing the prevalence of obesity include promoting breastfeeding, pre-packaged food (labelling) regulations, food-based dietary guidelines and the recent tax on sugar–sweetened beverages. Excess sugar consumption, especially from sugar-sweetened beverages has been consistent linked to increased risk of overweight and obesity in children, adolescents, and adults. Moreover, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) to address obesity.

In 2021, Nigeria joined more than 54 other countries that have introduced taxes on SSBs. The SSB tax which is embedded in the Finance Act of 2021, levies a ₦10 tax on each litre of all non-alcoholic and sugar sweetened carbonated drinks. Recent development shows that the federal government commenced the implementation of the SSB tax on 1st June 2022.

Global evidence has consistently revealed that taxation of sugar sweetened beverages is an effective policy tool for reducing their consumption and consequently reducing the prevalence of sugar induced diseases including obesity. For example, a modelling study shows that the United Kingdom’s tax on soft drinks could potentially save up to 144,000 persons from obesity annually, prevent 19,000 cases of type 2 diabetes and avoid 270,000 incidences of decayed teeth. In South Africa, a 10% tax on SSBs was predicted to avert 8,000 type 2 diabetes’ related premature deaths. Similarly, in Indonesia, empirical evidence shows that SSB tax can help to reduce the number of overweight and obese and prevent over a million cases of diabetes. In addition, numerous empirical studies shows that that effective taxes on SSBs can lead to significant reductions in Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs).

It is therefore evident and plausible to conclude that taxation of SSB in Nigeria has the potential to reduce the health and economic burden of obesity in the country. However, greater public support for the policy measure is needed in Nigeria, and the fiscal revenue should be earmarked for improving the healthcare system and as well as providing healthy alternatives such as safe drinking water.