I recently had the privilege of sharing my experiences on advancing data justice in African states, during an expert workshop organised by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) where I represented the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa. The workshop’s theme centred on 6 pillars to guide the conversation around data justice: power, participation, equity, access, knowledge and identity.

At CSEA, we commenced a research and advocacy project back in 2020 to advocate for a stronger data governance landscape in the region, as a means of putting in place necessary frameworks that can build trust in the digital and data economy, particularly in the context of regional trade, to ensure inclusive growth. Consequently, when we think about data justice, it is usually in terms of social justice, such that no one is exploited but rather everyone, not just a few, can benefit equitably from the opportunities that the data economy offers.

For this reason, CSEA has been clamouring for effective data regulation. However, we have observed some emerging trends that could pose a risk to encouraging data justice under two of the guiding pillars – power and participation.

Risk of power imbalance

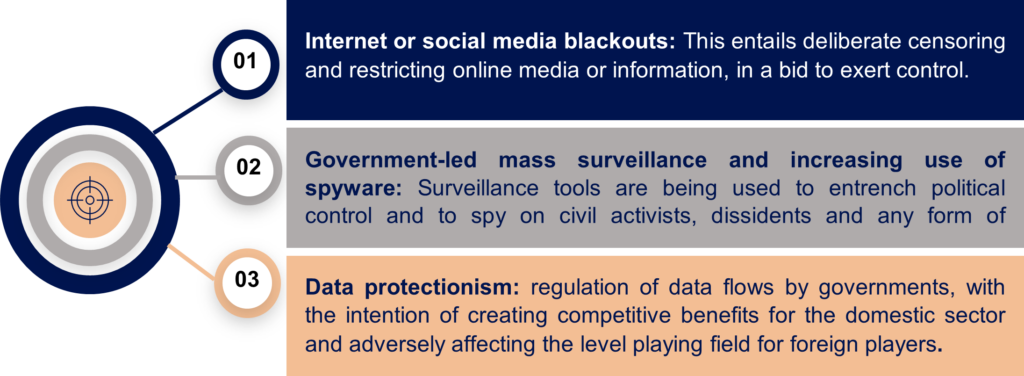

For effective data governance, there needs to be a balance of power between the different players in the ecosystem, including the data subjects. However, there is a real challenge of effectively balancing data regulatory approach(es) in a manner that does not result in over-regulation of data or state abuse of regulatory powers. The figure below highlights some of these trends observed across the region:

Source: CSEA (2022) – Curtailing State Extremism In Data Governance

The above can have counter-productive implications including; human rights violation on freedom of speech and association, heightened distrust, deprivation as a result of loss of livelihoods, a potential barrier to market entry for small firms, and increased uncertainty and costs for foreign investors making it unattractive to do business in such markets. Some countries have data localisation provisions that restrict data transfers beyond their borders. This can impair regional trade integration and the development of appropriate artificial intelligence systems which require vast amounts of data.

There is also a risk of power imbalance between African nations as it relates to data. CSEA’s Digital Preparedness Index shows that African countries are at varied stages of implementing data governance laws and frameworks. Only a few countries in the region are currently able to benefit from the rapid development of the data economy. Less digitally mature countries in the region are at risk of being left behind, due to the huge investments and resources needed to support an effective data regulatory mechanism. Inequality in human resource capacity affects countries’ ability to establish good data governance rules. Policymakers oftentimes, do not fully understand technological development to be able to adopt rules that steer rather than prevent innovation.

Inadequate public participation in data governance

Public participation in data governance is key to re-balancing power structures. For policymakers to effectively protect citizens’ data rights, extensive collaboration with, and input from the persons being protected is required. This goes beyond simple consultations on draft data policies or legislation. It entails the active involvement of the public in the policy vision, development and implementation of data governance frameworks. In reality, how can the public take an active role in data policy processes and decision-making when they are not fully aware of their rights and responsibilities and lack adequate knowledge on issues related to data governance? There is definitely scope for countries to commit to empowering citizens to engage in deciding how their data is governed.

As organisations like CIPESA and CSEA continue to advocate for increased data justice, some practical issues to ponder on and work towards finding solutions are:

- How can African countries achieve a balanced and robust data regulatory landscape?

- What actions are required to ensure less digitally mature countries in the region are not exploited or excluded from the data revolution?

- How can the public be empowered to take an active role in how their data is governed and in pressurising governments to implement more effective data regulations?