Poverty Alleviation via Education in Nigeria: Lessons from China

In Nigeria, approximately 50% of the estimated 193 million population live in poverty. In 2018, the World Poverty clock estimates that Nigeria has the highest number of people living in extreme poverty. These trends point to the need to rethink and rejig the government’s approach to poverty alleviation.

In rethinking Nigeria’s current approach, there are important lessons that could be drawn from emerging economies like China. Between 1990 and 2015, China effectively lifted 745 million out of poverty. This contributed to about 70% of the global poverty reduction over the period and the achievement has been described as the most impressive economic miracle in development history. While the roles of market reform, trade openness and state-led development initiatives in this ‘economic miracle’ are well documented, the role of education in the broader poverty alleviation strategies has been less emphasized. A new book on Poverty Alleviation in China[1] is drawing attention to the role of education in Chinese development narrative and there are many important lessons for countries like Nigeria which is facing similar developmental challenges. In this piece, we highlight four key lessons for Nigeria in order to reduce poverty via education.

First, vocational education was given priority among other levels of education in China. The elevation of the status of vocational training allowed a wider demographic of individuals (young and old) to acquire the benefits of skill development in the short-run through a flexible program. The programs ensured that the skills supplied within these communities matched local demand in order to effectively impact their experience. It also reduced the level of rural to urban migration as the campaign provided local opportunities, developed human capital within the rural areas which consequently broadened their capability. Although Nigeria has set up vocational training programs both in the formal 6-3-3 education system, as well as state governments and civil societies facilitated programs, its impact is limited. This is because the program is not widespread, lacks permeability and the programs are not standardised in delivery. Similarly, the lack of an overarching initiative focused on skill acquisition in the Nigerian education system limits its impact on poverty alleviation and also exclude some demographic groups in the development process.

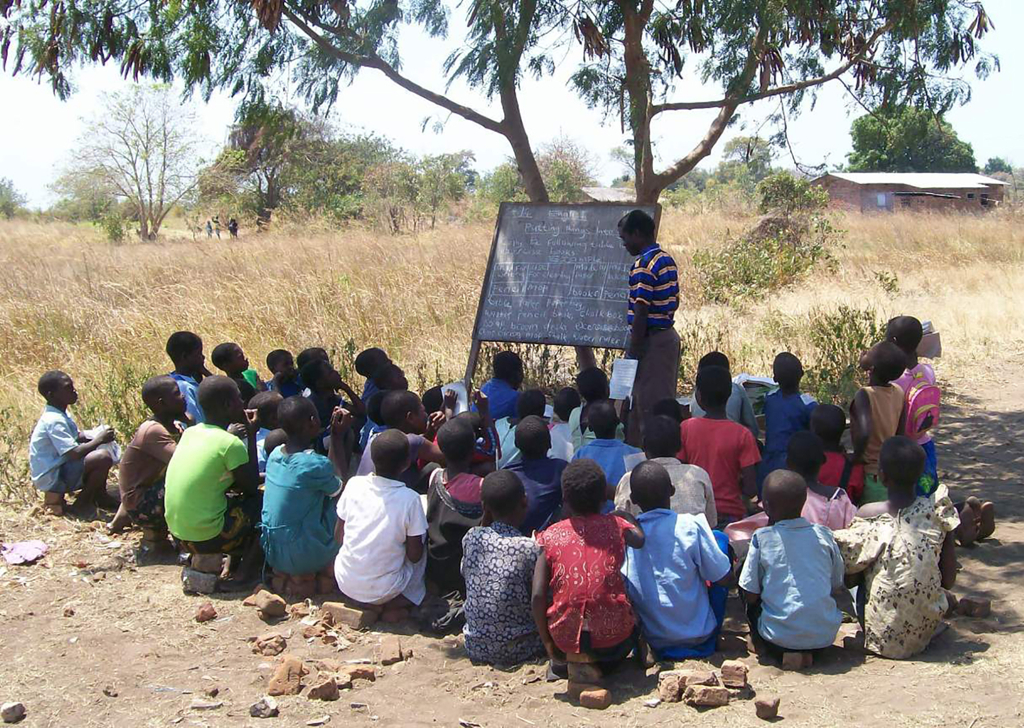

Second, education policy is considered as a subset of the grander economic policy, as such China’s education policy are jointly designed and implemented by the ministries of finance and education. The synergy between the finance and the educational ministry covers standardisation of education structures across various regions as well as teacher’s training and placement programme. The understanding that education policy is directly related to economic policy is one crucial area that presents an apparatus for policy design which Nigeria can learn from. For instance, the problem of out-of-school children in the Northern Nigeria, many scholars have observed that poverty and other economic fundamentals play a role in the problem[2]. However, policy interventions to address the problem have concentrated mainly on education sector driven solution like building more schools. Predictably, most of the educational interventions to out-of-school children issues in Nigeria have failed to deliver the expected outcome. Again, China’s approach to economic planning through mainstreaming poverty alleviation programs into the education policy could help Nigeria to simultaneously tackle the educational and economic challenges.

Third, China’s intervention in reaching disadvantaged communities and vulnerable groups that are not in school employed a good mix of free education and other incentives to encourage participation. The Chinese government provides region-specific subsidies for students within disadvantaged areas as well as loan schemes to encourage longer years of education in order to effectively improve their quality of life. There is an increasing recognition in the Nigerian context too that making education free does not automatically translate to more inclusion or increase enrolment, but that additional incentive is required to encourage more participation of the disadvantage groups. Also, constraints to schooling extend beyond costs and could be driven by cultural and behavioural factors. Responding to these non-cost elements require additional interventions even when education is free. The federal and state governments recent school feeding programme is an example of balance policy mix to improve inclusion. Going forward, it is crucial to expand the interventions to region-specific incentives to improve educational performance in Nigeria.

Fourth, it is reassuring that China with outstretched government’s

presence still recognizes and ensures robust community participation in its

education management. Besides allowing for supplementary training and

facilities by the private sector, government-own initiatives also use local

role models and organizations to secure wider buy-in from the public.The

organizations and individuals were involved in campaign and awareness programme

regarding education reform. In the Nigerian system where implementing reform is

difficult, more involvement of communities in education policy intervention

will be vital and could help restrain vested interests and better communicate

reform benefits to the public. This is because the local agents understand the

region-specific idiosyncrasies and factors to ensure efficient implantation and

implementation of policy. In pursuing poverty alleviation in Nigeria, education

system could play a significant role beyond its traditional functions of

socialization and capacity and knowledge development. Education can directly

work to reduce poverty through promoting inclusiveness, strengthen community

engagement and using vocational education as a springboard for development. The

Chinese experience offers a template which has worked to lift more than three

times the estimated Nigerian population out of poverty and fortunately it only

requires looking inward and building broad base local partnership.

[1] Editorial board of Poverty alleviation in China ‘Poverty-Alleviation via Education in China’,(2018), First edition

[2] Lincove, J. (2009). Determinants of schooling for boys and girls in Nigeria under a policy of free primary education. Economics of Education Review, 28(4), pp.474-484.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China