COVID-19 and the Shrinking Fiscal Space for Education in Nigeria

The immediate costs of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on education in Nigeria are evident. With school closures that have persisted for ten weeks, students - especially the most vulnerable, are missing out on learning. The government and individual schools are adapting by switching mediums and delivering learning through digital platforms. However, the stark digital divide (in terms of both infrastructure and knowledge) that plagues the country is resulting in an exacerbation of pre-existing educational inequalities. The cost of recovery will be high, but the sector will inevitably be confronted with a costlier issue: between the effects of the pandemic and crashing oil prices, the fiscal space to fund basic education will shrink significantly.

Revised Budget - Fall in revenue from the dual shock of COVID-19 and crashing oil prices

The prolonged disruption in economic activity due to the pandemic, combined with the collapse of oil prices and the reduction in demand for Nigeria’s oil products are severely impacting Nigeria’s fiscal position. The International Monetary Fund projects that the economy will contract by 3.4 percent in 2020, a fall from the previously anticipated 2 percent growth. The total budget, which was set at N10.59 trillion is in the process of being revised downward by about 15 percent. Oil and gas exports, which make up around 76.1 percent of Nigeria’s total exports and more than half of revenue, are predicted to fall drastically, with oil revenue being revised downward to N924 billion from N2.64 trillion. Non-oil revenue targets have also been revised downward by 10 percent, as industries across all sectors continue to grapple with the effects of the pandemic-induced disruption in economic activity. In sum, total revenue has been adjusted downward by 34 percent.

With regard to actual performance, the projected numbers are close to performance as at the end of Q1. The reported gross and net oil and gas revenues were short by over 28 percent and 31 percent respectively, and non-oil tax revenue was N269.41 billion, representing a shortfall of about 40 percent of the predicted amount for Q1.

Dissecting the effect on education financing

While we don’t know the full extent of the economic crisis on education spending, we attempted to make a prediction by looking at education spending during and after the most recent oil crisis in 2014, and factoring in accessible education expenditure information at both the federal and state levels. This section is divided into two: what we know (information that is readily available), and what we don’t know (unavailable information).

What we know: Looking at a past oil crisis and the Federal Budget

- Looking at a past oil crisis - a decline in education prioritization

We analysed GDP and education spending during the 2014 oil price crash, where a fall in crude oil prices from $100/barrel to $52.65 led to a decline in total budgetary allocation from N4.694 trillion to N4.493 trillion in 2014. The fall in crude oil prices negatively affected total allocation to education, as it declined from N496.783 billion to N484.26 billion, but the share of education budget was maintained, increasing slightly to 10.7 percent.

In 2016, crude oil prices further declined to $43.73, but total budgetary allocation grew to N6.06 trillion. At the time, the government was able to increase the budget (by increasing debt), however given the country’s current debt burden and the global nature of the pandemic, borrowing conditions could be unfriendly, and borrowing could further worsen the country’s fiscal crisis. Despite this increase, the budget for the education sector was reduced to N480.278 billion in 2016. The increase in budget and the decline in education spending led to a decline in education budget by 3 percentage points in 2016. Since 2016, and before the current oil crisis, oil prices have been recovering slowly, and both the total budget and allocation to the education sector have increased consistently. However, the education sector budget, as a share of total budget allocation, has steadily declined since, reaching its lowest level of 6 percent in 2020.

This trend is revealing. The value placed on education in Nigeria by the current administration can be gleaned by the drop in the share of education expenditure in the national budget, despite yearly increases in the budget. While both the national budget and the nominal amount allocated to education have increased, the share of education has been in a steady decline. Given that research has linked funding to education quality, to the extent that this decline persists, our education system will remain stagnated.

- Federal budget

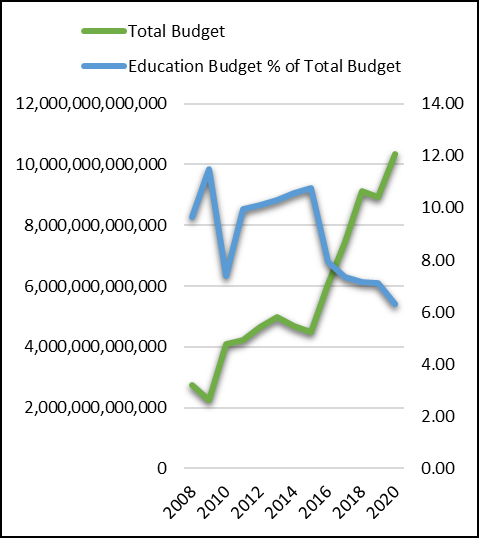

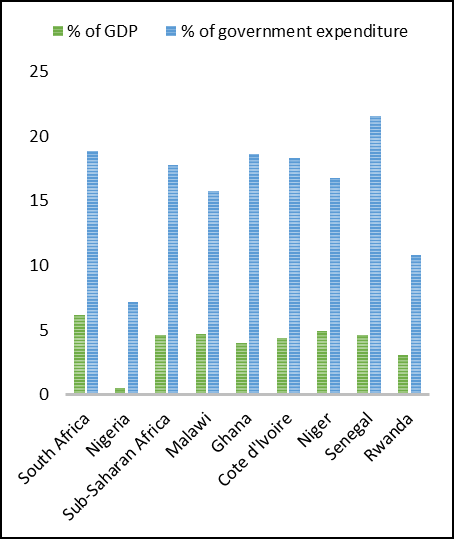

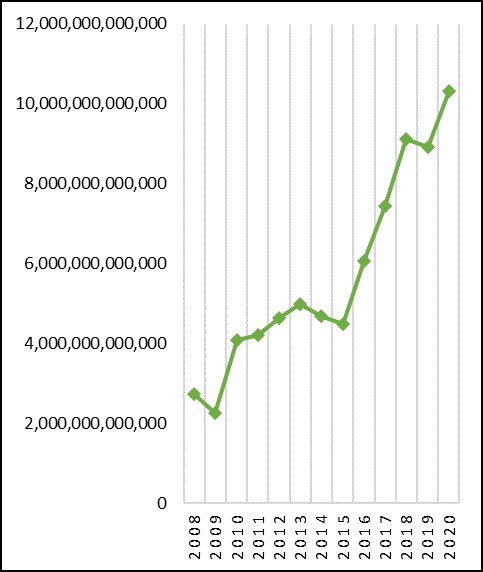

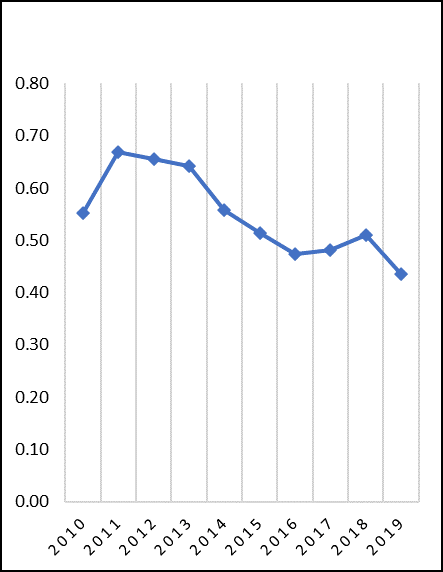

Nigerian budgets have tended to neglect the education sector in the past. In general, government spending is relatively small when compared with other African countries [see figure 2]. Prior to the current economic crisis, the education financing budget wavered around 9 - 10 percent of public expenditure {between 2008 and 2014: see figure 1}, against the recommended 15 percent to 20 percent. Despite an increase in the total budget by over 255 percent between 2008 and 2020 {see figure 3}, the education expenditure as a share of total budget has fallen from 9.64 percent to 6.32 percent within the same period. Public spending on education as a share of GDP has remained below 1 percent since 2010 against the recommended 4 percent to 6 percent, and has decreased steadily since 2011, from 0.67 percent to 0.44 percent in 2020 {see figure 4}.

Figure 1: Total Budget (Naira) and Education Budget (% of Total Budget)

Figure 2: Education Budget (% of GDP) and (% of government Expenditure)

Figure 3: Total Budgetary Allocation (Naira)

Figure 4: Education Expenditure as a Share of GDP (Percent)

The current economic crisis signifies that there will be a reduction in total budgetary allocation to the education sector, which would further dent the already neglected sector. The original education allocation for 2020 was N653 billion, roughly 6 percent of the total budget expenditure. Of this, N111.789 billion is the statutory transfer from the Federal Government (FG) to the Universal Basic Education (UBE) fund, which covers the FG’s contribution to basic education in Nigeria. The UBE fund is the main tool the government uses to influence spending on basic education at the state level. The remainder covers recurrent and capital expenditure for all education expenditure that fall within the purview of the FG.

Given the proposed cut in the budget, dataphyte, an open data organisation, reports that the FG has proposed a reduction in its budgetary allocation to education by almost 55 percent. This reduction is reflected in the government’s statutory transfer to the UBE Fund. Outside of the UBE fund contribution, funding of basic education is wholly within the purview of the state governments. Other than the proposed UBE cut, we don’t yet know how the total education budget will be impacted by the proposed budget cut; however, if the proportion of education spending were to remain the same (6 percent), and the budget was cut by 15 percent, the federal education budget is expected to be around 541 billion. This means that there could be a further reduction in education spending by N51 billion, which will affect other aspects of education spending outside of basic education.

Further, a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation that accounts for Nigeria’s revised growth projection, current education spending as a percent of total budget reveals that education spending could fall as low as N500 billion this year.

What we don’t know - State funding and availability of aid.

- State Funding

Provision of basic education (9 years between primary school and junior secondary school) is in the purview of state governments. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of information on state budget and spending on education across all states, which makes it difficult to infer the potential impact of the present economic crisis on state education expenditure. However, we do know two things that shed light on both the states’ ability to spend, and their current economic situations.

First, available state funding for basic education is limited for many states. The UBE funds available to the states can only be accessed upon meeting certain conditions, one of which is the provision of a 50 percent counterpart funding to match the FG’s contribution (which is why the UBE Fund is called a matching grant). Unfortunately, many states are unable to meet this condition; as of February 2020, over N73 Billion is yet to be accessed by several states. Their inability to match the FG grant is reflective of the fact that their education budgets are small, inadvertently affecting basic education in their states - a fact that is evident in the poor quality of both infrastructure and learning at the basic education levels.

Secondly, given the fact the lockdown measures and restriction on movements across states have taken a massive toll on the country’s economy, it is inevitable that this would result in budgetary shortfalls across all states in the country due to decreased tax revenue from all revenue streams. In 2019, the majority of state revenue was accrued through two sources: The Federation Accounts Allocation Committee (FAAC) (N2.47 trillion or 65 percent) and Internally Generated Revenue (IGR) (N1.33 trillion or 35 percent). The FAAC is a function of revenue derived through oil, which we know has been revised down by 35 percent. Of the IGR, 83.4 percent of IGR generated are from taxes while 16.6 percent are generated from state Ministries, Agencies and Departments (MDAs). Tax revenue through the IGR is also expected to decline given the reduction in sales, job losses and income cuts induced by lockdown measures and the slow down in the economy. Compounded by the need to increase public health spending across states in order to combat the virus, state budgets will also be adversely affected.

Given that we don’t know how much is being spent on education at the state levels, we cannot make a confident projection of how much state education budgets will fall by. But what we know is this: public (basic) education will suffer both during and after the pandemic.

- Education Aid - Can it plug the gap?

Measuring the contribution of aid to education spending in Nigeria is tasking. First, aid to the sector is highly decentralised, with donations focusing primarily on specific projects within individual states, and secondly, in general, there is paucity of data with regards to incoming funds into the sector. However, a report on the effect of aid on education financing in Nigeria found that external aid only contributed marginally to public expenditure of basic education in Nigeria. The report suggested that even a substantial increase in aid would do little to bridge the gap in the current level of funding and the amount required to achieve education goals. It found that between 1999 and 2009, education aid only contributed to 1.5 percent of total domestic expenditure (on primary education alone). Additionally, recent data from USAID reveals that in 2019, education aid to Nigeria was at its lowest after a peak in 2015 (at $84 million), falling 78.6 percent between 2015 and 2019.

Given this, and the global nature of the pandemic-induced economic crisis, it is unlikely that aid to the education sector will fill the education finance void. At best, education aid will remain at the same level, or at worst case, it will reduce. Though international organisations, the World Bank for example, have committed to boosting aid to support developing countries in their recovery, it will be difficult to extrapolate how much of this total aid will reach education sectors around the world.

Recommendations

Nigeria continues to lag behind in terms of education financing, and with the current national and global economic outlook, the prospects for increased financing in the immediate future are bleak. Given this, the government will need to make difficult decisions about how and where to channel scarce resources available at both the national and sectoral levels. With this in mind, there are a few key things to consider:

National level

- Prioritizing education funding: While there are a lot of moving parts involved in improving the access to quality education and inadvertently education outcomes, one key thing remains significant: money matters.

Empirical evidence suggests that lack of equitable and adequate funding is a key driver of unrealized education goals. Researchers have found that adjusting school spending by 10 percent leads to a reduction in test scores by around 7.8 standard deviation (10 percent cut), and increase in test scores by 0.05 to 0.09 standard deviations (10 percent increase). Access to financing has been attributed as one of the reasons why Nigeria did not achieve its Millennium Development Goal (MDGs) targets for Universal Primary Education and Education for All, and is probably an underlying factor behind the fact that no state in Nigeria is on track to meet the SDG Goal 4 target - ensuring inclusive and equitable education for all.

Money is a necessary underlying condition for achieving education goals. Increased access to financial resources provides the scope to achieve non-finance related education targets {indicators}. Education at all levels has suffered as a result of the pandemic, and by all estimates, students are lagging behind. We are at a critical juncture; ideally, the government would need to channel more resources into the sector to catch up, however, in a best case realistic situation, it will be important to at least maintain the pre-pandemic levels of financing.

Sector level

- Immediate - Supporting evidence-informed decision making: Money matters, but how money is spent is critical too. Given the scarcity of resources, it is important to monitor how resources are being allocated, and to determine if resources are achieving expected results/outcomes in order to maximize scarce resources for maximum impact. The government must channel resources and efforts toward creating a culture of learning through results-based monitoring and evaluation. All resource allocation decisions made within the sector should be augmented by three activities: tracking use of funds, measuring its outcomes/impacts against expected results, and making necessary adjustments based on findings. This should be supplemented by incorporating a results-based financing approach that removes the current arbitrary nature of funding, and directly links funding decisions to achieved results.

- Long-Term - Develop a strong National Education Account: There is paucity of readily accessible data on state level education financing and education aid across the country, making it difficult to determine how much is being spent on education financing across Nigeria. Additionally, data about private financing/household spending on education is also limited. Collating this data is important because it allows us to glean vital information, such as whether our problem is inadequate funding, or improper use of available funding. A solution to this is to build a strong and holistic National Education Account (NEA). An NEA provides a framework for comprehensive data collection and analysis that covers all sources of funding at all levels of education and across all types of education providers. A holistic NEA will allow us to see not just how much money is spent on education across Nigeria, but it will allow us to determine who is spending money, and what money is being spent on. Developing an NEA will be difficult, but UNESCO offers a step by step guideline to help countries in developing NEAs.

To conclude, increasing education financing, and improving data collection, tracking and impact of financing is no panacea for all of Nigeria’s education ills, but it offers a step in the right direction. Monitoring the flow of money through the system and ensuring effective use, provides a necessary condition for improving all other factors that matter for equitable access to quality education and improved outcomes.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China