How To Resolve The Tariff Disputes Blocking Nigeria’s Solar Project Pipeline?

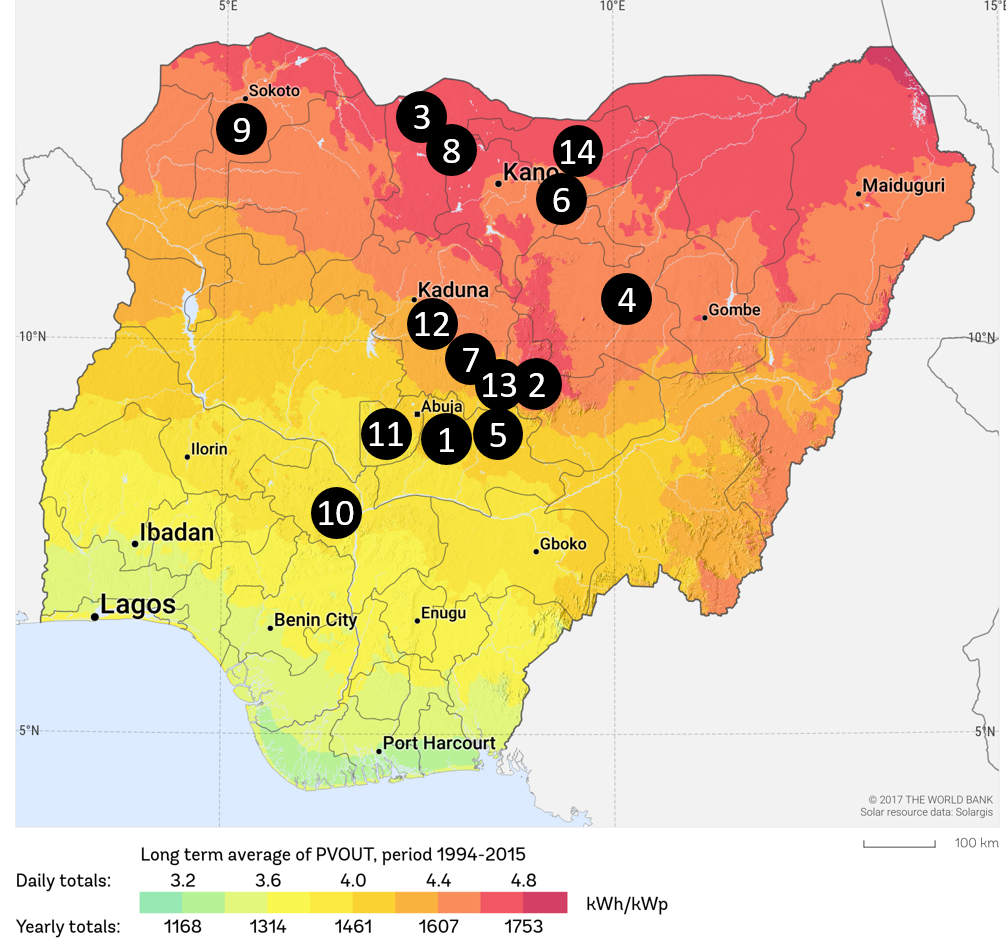

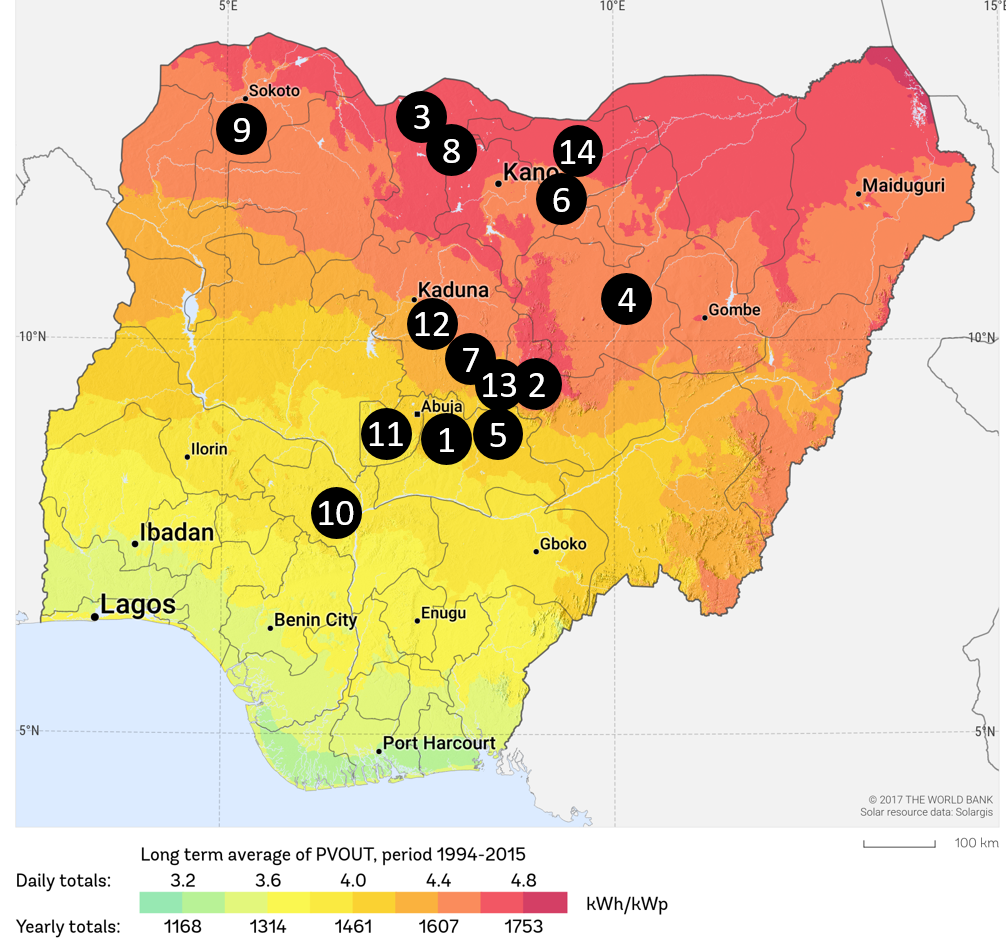

In 2016, Nigeria signed power purchase agreements (PPAs) worth US$2.5 billion with 14 independent power producers (IPPs) to build a total 1,125 megawatts of installed solar capacity for the national grid. Currently, grid power consists mainly of gas-fired power (85%) and hydropower (15%), with less than 1% solar. The solar IPPs are planned mostly in the northern parts of the country, where higher solar radiation is present (see map). However, put and call options agreements (PCOAs), essential to ensure the bankability of the project, are yet to be signed by twelve of the fourteen IPPs (see Table 1) due to extended negotiations on Partial Risk Guarantees with the World Bank and the African Development Bank.

The deadlock is caused by disagreements between the government and the IPPs on the PPA tariff structure. While IPPs want to sell power at the initially agreed US$0.115 per kWh, the government is insisting on a tariff of US$0.075 per kWh, citing declining solar costs and comparable projects in countries such as Senegal (US$0.05/kWh) and Zambia (US$0.06/kWh).1

Key Factors for Resolution

- Fair and Competitive Pricing. While the average cost of procuring solar power has declined globally by 74% since 2009, markets differ greatly across countries.2 The compromise must reflect the true risk-adjusted costs of solar systems in Nigeria.3 A balance should be struck between generating appropriate investor returns while delivering inexpensive energy to impoverished areas short of power.

- Commercial Viability and Cost Recovery. Gas suppliers, GenCos, and DisCos are already affected by tariffs set below cost recovery (averaging US$0.066/kWh), which inevitably lead to stalled projects.4

- Country Risk Premium. Nigeria is already a high-risk market. Disregarding legally-binding contracts agreed in the PPAs may contribute to weakening investor trust, raising the country’s overall investment risk profile, negatively affecting future investment and, ultimately, energy prices.

Conclusion: Broaden the tools to find a solution. The Government and investors can renegotiate and compromise in these deadlocks through resourceful policy mechanisms that could yield more desirable outcomes for both parties. These include the removal of the import duty on solar components to reduce total costs for the power producers. It could also include a capacity scale down to a captive market, for instance secluding reliable solar systems primarily for communities with high commercial, agricultural and industrial activities – to ensure that the government and populace get the most out of the new power projects. Different tariffs could also be applied to different IPPs on the grounds of certain considerations such as project locations and sunk costs.

Table 1: The 14 solar IPP companies and project overview| Company | Capacity | State | PCOA Signed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Afrinergia Power Limited | 50 MW | Nasarawa | April 2017 (7.5c/kWh) |

| 2. | CT Cosmos Limited | 70 MW | Plateau | April 2017 (7.5c/kWh) |

| 3. | Pan Africa Solar | 75 MW | Katsina | Not Signed |

| 4. | Nigeria Solar Capital Partners | 100 MW | Bauchi | Not Signed |

| 5. | Motir Desable Limited | 100 MW | Nasarawa | Not Signed |

| 6. | Nova Scotia Power Dev Ltd | 80 MW | Jigawa | Not Signed |

| 7. | Anjeed Innova Group | 100 MW | Kaduna | Not Signed |

| 8. | Nova Solar 5 Farm Limited | 100 MW | Katsina | Not Signed |

| 9. | KvK Power Limited | 100 MW | Sokoto | Not Signed |

| 10. | Middle Band Solar One Limited | 100 MW | Kogi | Not Signed |

| 11. | LR Aaron Power Limited | 100 MW | Abuja | Not Signed |

| 12. | En Africa | 50 MW | Kaduna | Not Signed |

| 13. | Quaint Abiba Power Limited | 50 MW | Kaduna | Not Signed |

| 14. | Oriental Renewable Solutions | 50 MW | Jigawa | Not Signed |

This Memo was drafted in collaboration with Patrick Okigbo of Nextier Advisory

This article was first published on energy for growth hub

This Memo was drafted in collaboration with Patrick Okigbo of Nextier Advisory

This article was first published on energy for growth hub

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China