COVID 19 and the Informal Sector in Nigeria: The Socio-Economic Cost Implications

As the world is currently being ravaged by the COVID-19 pandemic, nations are grappling with how to contain the spread and limit its effect with their borders. Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, has reported 873 cases of COVID-19, and 28 deaths as of April 23rd. The government has implemented a range of measures to curb the spread, including the closure of international airports, primary, secondary and tertiary institutions, markets/stores, and halting of all public gatherings. On March 29th, a four-week statewide[1] lockdown was declared in three major states - Lagos, Abuja and Ogun - halting all non-essential activities across all three states.

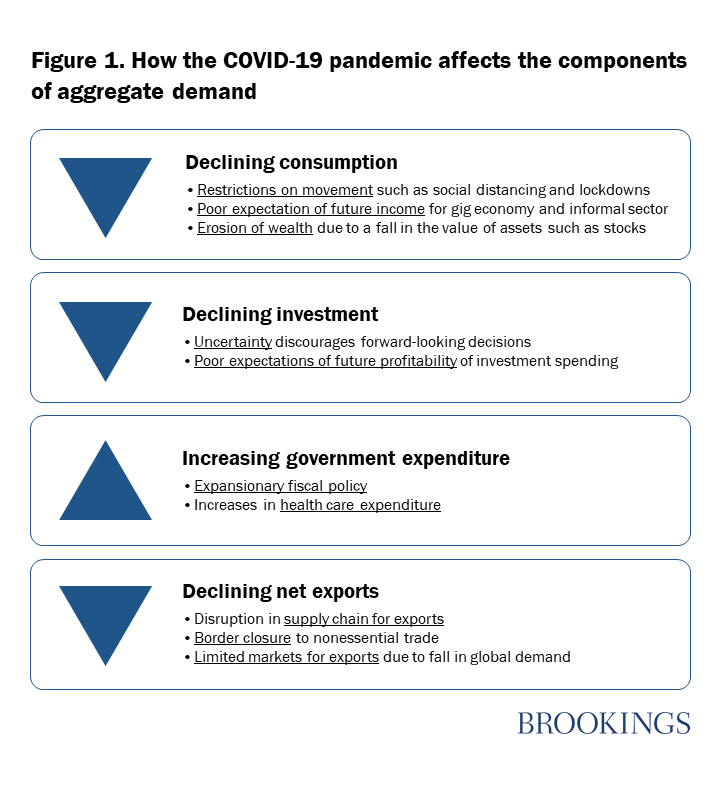

These closures, while essential, are having negative ripple effects across all sectors and segments of the country. The macro effects on the economy have been documented, ranging from a fall in both aggregate supply and demand, decline in exports and rise in overall government spending, but much less has been said about the effects on the people who are the first to bear the brunt of the impact: individuals, micro and small enterprises, and daily wage earners operating in the informal sector[2].

Profile of People Affected

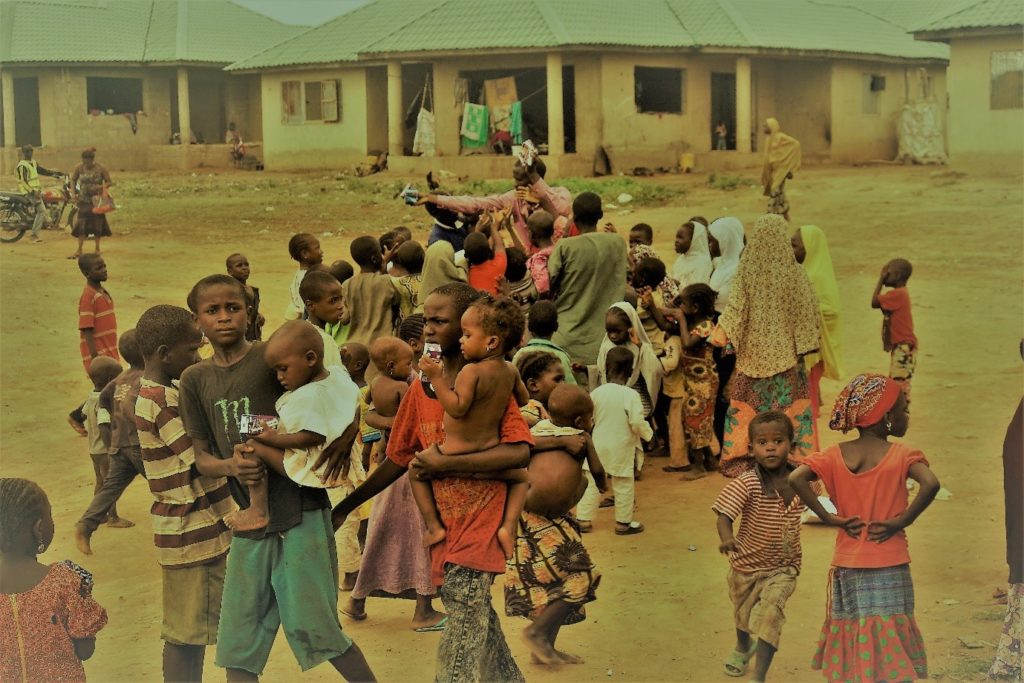

According to the International Labour Organisation, in Nigeria, over 80% of working people are employed in the informal sector. The affected lockdown states include three of the most urbanized states in Nigeria, signifying that the impact of the lockdown would be skewed toward those who perform urban informal sector economic activities. Such activities include (but is not limited to) street trading and vending, micro and small scale manufacturing, repair and service provision, home-based enterprises, informal employees of formal enterprises (making daily/weekly wages).

For the vast majority of people engaged in these economic activities, they are daily-wage earners who either rely on income generated from going to work at a physical location on a daily basis/weekly basis, be it as an employee for someone, or as a micro/small entrepreneur.

People in this population belong to the category of people who are most vulnerable to the negative economic shocks surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. Their income-generating activities are more closely tied to the daily whims of the market. To wit, for this category of people, their ability to meet their immediate basic needs such as access to food, shelter, and health services, predicated on daily access to face-to-face interactions and customer flow. This article provides an in-depth description of the group most likely to be affected by the lockdown.

Essentially, this lockdown effectively stops all income-generating activities for people engaged in non-essential services. Additionally, with this lockdown occurring in urbanized states, there’s the intensifying impact of rising food prices in these states, driven by disrupted food supply chains and panic buying. For this population, faced with a loss of access to income-generating activities, and without the luxury of an income that allows bulk purchasing and the home infrastructure (electricity and adequate refrigeration to store food), the impact of slight increases in the cost of living could be dire.

Liquid Precautionary Savings

For most households whose income stream has been temporarily blocked, they would need to find other means to sustain their livelihoods during this lockdown period. Cue in savings, which is widely known to cushion and help manage the uncertainty that weighs on an individual/household’s income. The general advice is to build precautionary savings during periods of high income, to help smooth consumption during periods of low income. For those who have access to modest incomes far and above their basic needs, this advice is practical; however, for the vast majority of people being negatively impacted by the COVID-19, this advice might not be feasible.

Given the link between poverty and the informal sector in Nigeria, it is realistic to assume that the informal sector serves as a source of employment for the poor, absorbing low-level education holders, and those unable to secure wage employment in the formal sector. Therefore, income levels are relatively lower for people working in the informal sector. Though it is an avenue to secure a reasonable source of income for people, the informal sector is also riddled with challenges, not least of which is income security.

The interplay of these factors - low income and income security, coupled with huge familial responsibilities that are representative of Nigerian households, high cost of living in urban areas, and poor social safety nets, translates to a hand-to-mouth mode of living for urban informal sector workers. For the vast majority of micro and small businesses/daily earners, their earnings are so low that the concept of ‘rainy-day’ savings/investments is a luxury. Income in this population is generally so low that it offers less wiggle room to make choices about how to use money. The urgency to satisfy immediate needs given limited resources blankets the capacity to contemplate a savings/investment plan for the future.

This is not to negate the fact that households in this population engage in several consumption smoothing mechanisms. However, for individuals working in this sector, their incomes are only fluid enough to allow them consumption smoothing for periods of anticipated income fluctuations, for example, based on seasons. Some may have savings in forms that do not lend themselves to immediate liquidity e.g. assets. For some micro-entrepreneurs, they might be stuck with the repayment and high-interest loans associated with predatory loans; this is especially pertinent for women who are often the target and recipients of microloans. For households with some savings, some are overburdened (because a large proportion of the population is dependent on a large workforce), and for others, the persistence of the lockdown beyond a certain time period will throw them into a precarious situation.

The reality is bleak: the COVID-19 pandemic has stretched the consumption volatility of financially constrained households who are regularly unable to smooth consumption.

Current Government Intervention

The Federal Government (FG) has taken several steps toward cushioning the effect of this lockdown on the most vulnerable populations. As of (insert date), the following interventions had been announced:

- A plan to distribute food rations to the most vulnerable households in the three lockdown states. The plan is to deploy 77,000 metric tons of food to vulnerable households in the three affected states, and to continue school feeding programs across the country.

- A conditional cash transfer of N20,000 per month (up to four months) to the most vulnerable households. For identifying the most vulnerable households, the FG is utilizing the National Social Register of Poor and Vulnerable Households set up in 2016 by the Buhari administration.

- The Lagos state government announced a plan to feed at least 200,000 households.

- The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) announced a N50 billion targeted credit facility geared towards households, and Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

These interventions, however commendable, will likely not be enough to mitigate the losses that will accrue to households during the lockdown, and unfortunately would likely not reach all the people affected. As has been depicted above, the vast majority of the people affected would be ‘the urban poor’. As this article shows, the current social protection registry consists largely of agricultural and rural households, who are less likely to be negatively affected by the economic shocks of COVID-19. For various reasons, most importantly being that most agrarian/rural households tend to produce what they eat, and the food supply chain has been excluded from the lockdown.

The National Social Register consists of about 11 million people from about 2.6 million households. If at all the register contained the target population, it doesn’t begin to scrape the bottom of the barrel. For example, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the informal economy in Lagos employs almost 5.5 million people, representing about three-quarters of the state's 7.5 million labour force population. With 5.5 million people in Lagos alone, catering to the needs of at least three-quarters of the 13 million non-working population, these cash transfers are unlikely to make a huge dent. The president had mentioned that the number of households on the registry would be increased by 1 million, to about 3.6 million, but even with this, the reach is limited and targeting issues still exist.

Some systemic problems also arise. In general, the government has not announced any key details of any of the interventions announced, which limits the scope for accountability. No information is known about who is getting the money, therefore no evaluative judgment can be made about the impact of the funds. Additionally, given the lack of a comprehensive database of informal workers, and their institutional financial exclusion, there is the added risk that the funds will not reach the right people. With the credit facility being provided by the CBN, beneficiaries can access funds to a ceiling of N3 million; however, qualification requires proof of collateral, such as property, which is exclusionary for the most vulnerable households.

On a macro level, these safety nets cannot be sustained for long periods of time. A lockdown means that the economy, in general, is not producing, and people are not consuming. Given the recent drop in oil prices, a halt in economic activities within the country also signifies that the country will be generating meager revenue. Additionally, remittances from international development partners will decrease, given the global socio-economic impact of the pandemic. Given these, It would be impossible to continue wealth distribution if there are no economic activities yielding revenue for the government.

What are/will be the effects? - Two Possible Scenarios

Scenario 1 - The lockdown is lifted after the end of the fourth week: Ideal case, given the circumstances.

Nigeria is able to contain the virus and flatten the proverbial infection curve by the end of the four-week lock-down period. The affected states can begin the process of slowly restarting the economy and recovering from the effects of the lockdown, making sure to create and adhere to well thought out and conscientiously managed restrictions to prevent a second wave/widespread outbreak. Some sectors of the economy, tourism for example, will still be halted, especially if the global threat still persists. Given the circumstances, this will be the best-case scenario. But even at this, for this population, the economic ramifications and the disruptions to livelihoods are inevitable and will be long-term, and the rebuilding process will outlast the presence of the virus in the country.

There will be a reduction in overall consumer purchasing power because of widespread job loss and lost earning time. Recovery will be slow, but without a second-wave of the infections, it will be steady. People are able to return to work or venture out to seek new employment opportunities.

Scenario 2 - Lockdown is extended for another one-month period (or an undefined time): A series of compounding events triggering a vicious reinforcing cycle: As coronavirus deepens poverty, poverty worsens its spread.

The nation continues to see a rise in the number of new COVID-19 cases across the country, forcing a situation where the lockdown is extended. Travel across states is banned, so emigration out of the affected states would be difficult.

At a certain point, people will no longer be able to bear the suffering associated with the lockdown and will be forced to venture out in search of a chance to survive. Factoring out any punishments from the government associated with breaking the lockdown rules, prematurely returning to life-as-usual, especially in a state as densely populated as Lagos, bears the real risk of exacerbating and worsening the spread of the virus. An outbreak caused by such a situation will disproportionately affect people in the lower socio-economic category i.e. the people who actually need to take the risk of exposure. Without the luxury of adequate medical facilities, or multi-room houses, the spread across this population will be exponential and likely deadlier than we are currently experiencing.

In this scenario, for the vast majority of affected people, the trade-off is costly: risk the exposure to and probable death by the COVID-19 virus, or death by hunger? Alas, getting infected by the virus might be the lesser of the two evils.

General Societal Effects

For society at large, the consequences could be damning. Overall, these economic and social impacts of the pandemic are set to exacerbate existing societal vulnerabilities. There will be an increase in the persistence and prevalence of poverty with more people being plunged below the poverty line. The gap between the haves and the have nots will widen, and existing social and economic divisions will be intensified.

There has been an increase in social ills, unrest, and theft that is already being reported - due partly to hunger stemming from a loss of jobs, and an increase in the general animosity and resentment that is triggered by socio-economic divides. Security experts have predicted that this is likely to persist well beyond the epidemic.

Long term, specific policy measures must urgently be taken to recognize the value and contribution of the informal economy to society. In the interim, however, the government and private sector need to band together to support individuals and households in this sector.

What can be done?

Action for the government - As a nation, we do not have the luxury of locking down three major states in the nation beyond a one-month period, and the government needs to adequately support the vulnerable population during this time. There is no single silver bullet strategy to solve the problem, and given the limited fiscal capacity of the government, there is a narrow scope for a robust and sustained stimulus package. However, there are a couple of things the government can do to make the best use of available resources:

- Better targeting of the N20,000 stimulus package funds. This article shares some targeting strategies.

- Reduced restrictions for access to CBN loans to make it accessible to the most vulnerable. In line with the loans, the bank would need to engage in sensitization programs, to reach a vast number of micro and small entrepreneurs and assist them in filling out applications or putting together application requirements.

- Stop police harassment of informal regions, which has resulted in the confiscation of goods, fines or physical violence and abuse.

Ultimately, the government also needs to learn from this experience, to develop a proper disaggregated database covering all segments of the population, and to develop better social safety nets to cushion the most vulnerable people during this time.

Actions for private sector actors - The private sector will also have a critical role in supporting and complementing the efforts of the government in supporting the most affected during this precarious time. For employers who have staff that are daily earners (fixed pay or commission workers), as much as possible, they would need to ensure employment continuity for their staff. Given that private sector employers are also not immune from the impact of the economic fallout, they might not be able to sustain their employees during this time; however, rehiring the same employees when the economy restarts would reduce the economic costs on the staff.

Individuals and households with residual income can work toward boosting the local economy once the economy restarts, by supporting local artisans, boost their consumption of local produce, and patronize local services.

We as a society have a moral imperative to support the most affected amongst us. But beyond the moral, there is also an economic one; without effective support for the urban poor, the public health measures implemented to curb the spread of COVID-19 will disintegrate. If this happens, there is a possibility that the nation will experience a wider outbreak of the virus, which could throw us into a longer lock-down in the future. This, unfortunately, could topple the nation into a recession. While we are fighting to curb the spread of the COVID-19, another equally important societal virus lurks poverty. For Nigeria, the economic costs from the risk-control measures are mounting, and may very well outpace and outlast the health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

[1] Initially two weeks, and extended on April 14th, for another two weeks.

[2]Our definition of informality encompasses both formal sector workers who are micro and small enterprises and whose businesses are dependent on daily interactions with customers.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China