Why Nigeria should Strengthen Mobile Money: Some Stylized Facts

Nigeria continues to miss its financial inclusion targets. Many constraints around the formal banking system have meant that a greater percentage of the Nigerian population remains excluded from the formal financial sector. This article highlights the need to strengthen mobile money as a means of driving financial inclusion in Nigeria.

Introduction

The financial sector plays five crucial roles in the growth of any economy. One is easing the exchange of goods and services by providing a payment system that enables economic agents to pay for goods and services, thereby facilitating trade in the economy; Two is mobilising and pooling savings from savers and, thus, making the proceeds from such fund available for firms in need of funding Three is acquiring and processing information about enterprises and possible investment projects, thus enhancing efficiency in the allocation of investment funds in the economy; Four is monitoring investment and carrying out corporate governance; five is diversifying, increasing liquidity and reducing investment risk (Caporale, Rault, Sova, & Sova, 2009).

Among the five channels enumerated, mobile money finds its place within the first (easing the exchange of goods and services through the provision of a payment system which enables economic agents to pay for goods and services, thereby facilitating trade in the economy). Mobile money technology allows people to receive, store and spend money using a mobile phone. It neither requires one to own a bank account nor does it require internet. It is sometimes referred to as a mobile wallet (IGI-Global, 2022). Thus, it is a crucial driver of financial inclusion, especially among the unbanked in remote areas who also lack access to internet facilities and among traders in the informal economy. Mobile money gains its acceptance by this population demography as it requires minimal digital skills. If one can send an SMS using a mobile phone, they already have the digital skills to operate mobile money.

While Mobile money is considered a key driver of financial inclusion, there has not been enough attention by the Nigerian government to create an ecosystem where mobile money operations can thrive. Thus, leading to the inevitable consistent dwindling of financial inclusion. Since 2012 when the CBN launched the financial inclusion framework, progress has been slow due to several constraints identified by stakeholders, among which include the high capital cost of investments in mobile money, bureaucratic procedures and the requirement for KYC, which involves sim-NIN linkage. The federal government’s projection of financial inclusion in its 2012 National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS), revised in 2018, was to achieve 70% financial inclusion by the year 2020. However, only 64% inclusion has been achieved in the last quarter of 2022, which is a variance of 6% from the target. Given that countries like Kenya, which prioritised mobile money as a key financial inclusion driver, achieved a remarkable increase in financial inclusion, it would be a smart strategy for Nigeria’s government to pursue a similar objective.

Due to existing obstacles in operating a formal bank in Nigeria, especially the need for too many document requirements for opening an account and lack of access to banks in remote areas, it can be argued that the Nigerian government cannot achieve its financial inclusion targets of 95% by 2024 without putting mobile money at the forefront of its Financial Inclusion strategy. But before further comments, it would be vital to explain what mobile money is about and how it works.

The Mobile Money project was jointly launched by the GSM Association (GSMA) and Western Union in October 2007 to help the financially excluded to access financial services (Bello & Adenuga, 2013). The initiative comes in three models, which are, the operator-centric model (which involves only the mobile network providers such as the MTN mobile money), the bank-driven model (which is set up and managed by the bank like the POS), and the collaboration model (involving both banks and mobile providers like the use of USSD) . The operator-centric model is the only model that does not require one to own a formal bank account, making it the easiest model for driving financial inclusion. The Network providers offer the technology, operate the transactions and compensate the system without bank involvement or the need for a bank. Because mobile operators already have a large customer base, they benefit from service fees, and in turn, customers are happy to make quick and convenient payment transactions, and the result is an economy with high financial inclusion.

Despite the fast-growing Fintech sector in Nigeria, Porteous & Omusi (2020) report that about 36.8% of the Nigerian population still lacks access to financial services, which necessitates a need for more flexible financial inclusion strategies such as the non-bank-centric mobile money models. This is evident from the statistics quoted by The Economist that the value of mobile money transfers and e-payments in 2018 was only 1.4% of the GDP in Nigeria, compared to 44% of Kenya’s GDP (The Economist, 2019).

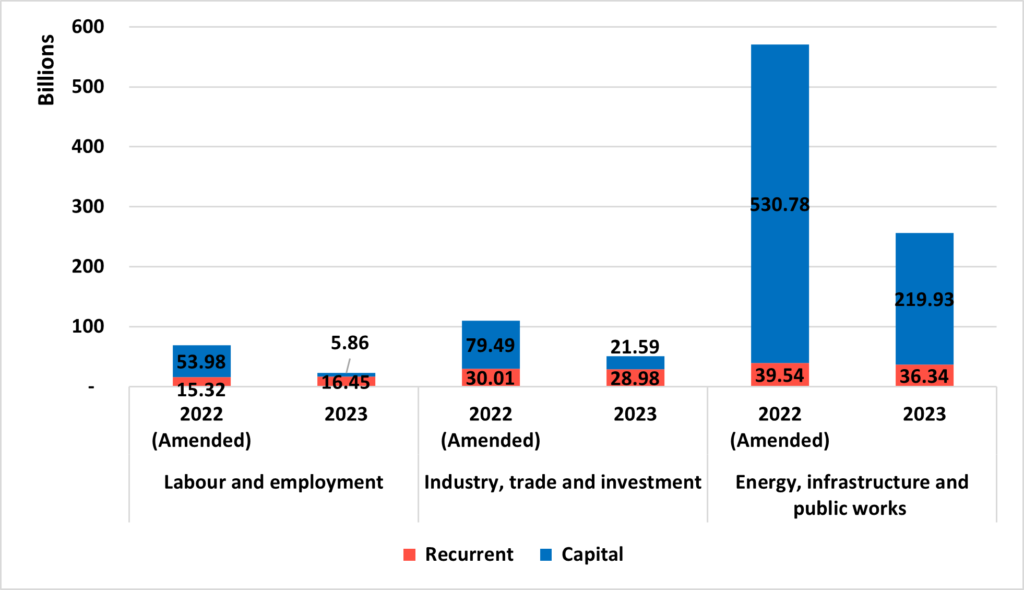

(Account ownership at a financial institution or with a mobile-money-service provider (% of population ages 15+) - Nigeria, Kenya, Sub-Saharan Africa

Figure 1. Financial Inclusion

Source (Worldbank 2022)

As shown in Figure 1, financial inclusion in Nigeria is below the Sub-Saharan African average. Meanwhile, Kenya surpasses the Sub-Saharan African average, which could be attributed to the success of the M-PESA mobile money project.

This operator-centric model remains the key to driving financial inclusion among the poor, uneducated and unbanked. The model would ensure that all classes of society would have greater access to financial services. A good example of a successful operator-centric model is the M-PESA project in Kenya. M-PESA, which stands for mobile money transfer service, ‘M’ for mobile and “PESA” for money in Swahili, was introduced in 2007 in association with Safaricom, Kenya’s largest mobile network provider. Vodafone, the largest shareholder in Safaricom, founded and owns M-PESA. Since its introduction in 2007, M-PESA has seen tremendous success and serves as the best illustration of a typical m-money service for the unbanked and underbanked. Over 9.4 million consumers and more than 18,000 agents have used the M-PESA initiative since it began in 2007 for person-to-person (P2P) transfers. According to Bello & Adenuga (2013), there is hardly a home in Kenya that does not utilise M-PESA. In fact, up to 13% of Kenya’s GDP was transferred using M-PESA between 2009 and 2010. Through M-PESA, users can make deposits into an account held on their mobile devices, transfer balances to other users (including vendors of goods and services), and exchange deposits for cash via SMS technology.

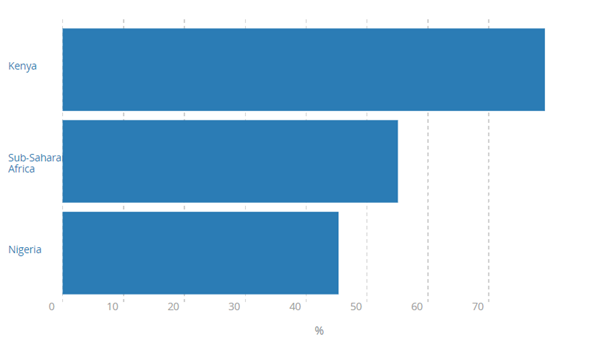

Mobile money accounts have also begun to gain popularity in the rest of Africa. However, Nigeria is lagging. According to Global Findex latest data (2017), many African countries (especially Kenya) have shown remarkable improvement in ownership of mobile money accounts, but Nigeria has remained largely stagnant.

Figure 2. Ownership of mobile money accounts in Sub-Saharan Africa

As shown in the diagram in Figure 2, it is evident that Sub-Saharan Africa has made good progress in terms of ownership of mobile money accounts, moving from 12% in 2014 to 21% in 2017. In Kenya, while a small percentage did not have access to mobile money accounts in 2014, this changed drastically in 2017, with close to 100% of the population owning mobile money accounts due to the ease of use of the service. In Nigeria, however, the numbers have remained low at about 0-9% of the population from 2014 to 2017.

Currently, in Nigeria, the dominant form of mobile money is the collaborative model (between the banks and the mobile operators), i.e., the use of USSD to send money from your bank account to another bank account. The problem with this model is that it requires you to have a formal bank account. The tedious process and document requirements to own a bank account in Nigeria make it challenging for people in remote areas and villages to own and operate a bank account. Thus, necessitating the need for investments in operator-centric models. Although there are existing operator-centric models in Nigeria, such as the Paga wallet founded in 2009, the adoption rate remains minimal, which could be attributed to constraints limiting the private sector from innovating and expanding. Thus, the success of mobile money in Nigeria might require the collaboration (investments) of both the public and private sectors in forming public-private partnerships (PPP).

There is no doubt that mobile money has the potential to drive economic growth by encouraging savings which leads to investments. Beshouri et al. (2010) affirm that mobile money has the potential to allow two important questions to be addressed at the same time: on the demand side, it represents an opportunity for financial inclusion among a population that is underserved by traditional banking services. On the supply side, they explain that it opens up possibilities for financial institutions to deliver a great diversity of services at low cost to a large clientele of the poorest sections of society and people living in remote areas.

In the following section, four key facts about why the mobile money system should be prioritised in Nigeria are presented.

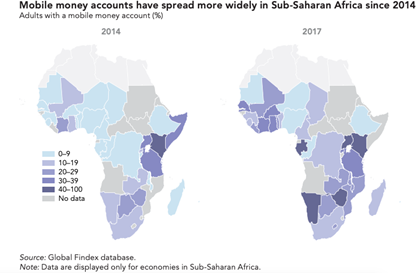

FACT 1: Nigeria’s high mobile phone penetration can support faster mobile money penetration

Although the M-PESA in Kenya has recorded massive success, Nigeria’s transaction volume in mobile money will be even higher due to its vast population. Since 2005, Nigeria has had consistently higher mobile phone penetration than the Sub-Saharan African average (WorldBank, 2022). As shown in figure 3, it is evident that in comparison to the Sub-saharan average (although still slightly lower than Kenya), Nigeria has had a higher mobile phone subscription rate since 2005, which shows the country’s potential in mobile money operations.

Figure 3. Mobile Cellular subscriptions (per 100 people)

Source: World Bank (2022)

Given that Nigeria’s mobile phone penetration is still lower than Kenya’s despite having a higher population, the policy route to maximise mobile money will therefore include a strategy to increase mobile phone penetration in Nigeria

FACT 2: Mobile Money Drives Financial Inclusion

Credit and deposits are now easier to obtain by the unbanked as a result of mobile money service accessibility: mobile money lower transaction costs, particularly those associated with maintaining physical bank branches. In addition, Andrianaivo & Kpodar (2011) affirm that the increasing use of mobile telephony in developing countries has contributed to the emergence of branchless banking services, thereby improving financial inclusion. They add that mobile money allows expansion and access to financial services for previously underserved groups in developing countries, emphasising that this improved access to financial services for those who are underserved contributes to closing the infrastructure gap in the financial sector, particularly in developing nations where the expenses of travel and time are quite high for conventional banking services.

FACT 3: Financial Inclusion Contributes to Economic Development

Financial inclusion as a strategy has emerged as a global concern for policy, including in Nigeria. It is seen as a means of fostering inclusive Economic Growth and a transmission mechanism for eradicating poverty (Stephen and Wakdok, 2020). Access to financial services stimulates incentives for private investments made by people and thus promotes economic growth (Andrianaivo & Kpodar, 2011). Many empirical papers have presented overriding evidence of a positive link between financial inclusion and economic growth (Chakraborty and Abraham, 2021). The common channel through which financial inclusion impacts economic growth is that financial inclusion encourages savings which then lead to investment, and in turn, investment leads to economic growth. Financial inclusion (especially ownership of a mobile money account) also encourages entrepreneurial activities, especially in remote areas where there is a high risk of carrying physical cash. This growth of entrepreneurship helps to reduce poverty and foster economic development.

IMF Studies for African countries such as Kpodar and Andrianaivo (2011) have also shown that while mobile phone penetration positively impacts economic growth, the channel through which this happens is financial inclusion fostered by the use of mobile phones for financial transactions. These same findings are replicated in a recent study by Ifediora et al (2022) for African countries, where the authors demonstrate that ownership of mobile money accounts and mobile money transactions foster economic growth

Finally, the supply-leading hypothesis, which states that the development of the financial sector gives rise to an increase in economic growth, has been validated by several authors (McKinnon, 1973; Shaw, 1973; Schumpeter, 1934; Wesiah and Onyekwere, 2021; Apergis, Filippdis and Economidou, 2007; Vazakidis and Adamopoulos, 2011; Nyasha and Odhiambo, 2015). The authors are of the view that financial institutions and markets trigger economic growth through the efficient allocation of financial resources to the most productive investments.

Fact 4: Mobile Money Makes Lives Easier

Mobile money affects lives positively by making day-to-day transactions hassle-free. For instance, because of mobile money, people in remote areas can easily transfer money from any location to any location just by pressing a few commands on their mobile phones. They no longer need to commute to the bank to wait in a long queue before they can make a deposit. Thus, mobile money saves both time and cost. Secondly, mobile money drives a digital economy that makes people live happier with less banking stress. Another important benefit is that with mobile money, cash payments will be reduced, and traceable payment methods (especially in the informal economy) make it easy to prevent fraud. Back in the days when cash was used, anyone could easily deny that you made a payment to them. But with mobile money, it is easy to make such payments cashless, which is traceable and cannot be denied.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China