The 2020 National Budget: right cycle is great, but implementation is better

The reasons for underperformance of budgets are beyond wrong cycle or under-collection of oil revenue. But rather the biggest issues lie in over-ambitious projections, under-performing non-oil revenue and unspent funds by MDAs

Budget cycle in Nigeria is expected to run from January and December. In practise however, budgets are nearly never passed until late into the second quarter of the year. The irregularities in cycle has affected budget implementation and credibility. It is therefore reassuring that efforts are being make to get the budget cycle right with the 2020 national budget. Already, the appropriation bill presentation is the earliest in the last 10years. The parliament has also rolled out plans to ensure speedy passage of the appropriation bill by November and possible assent in December.

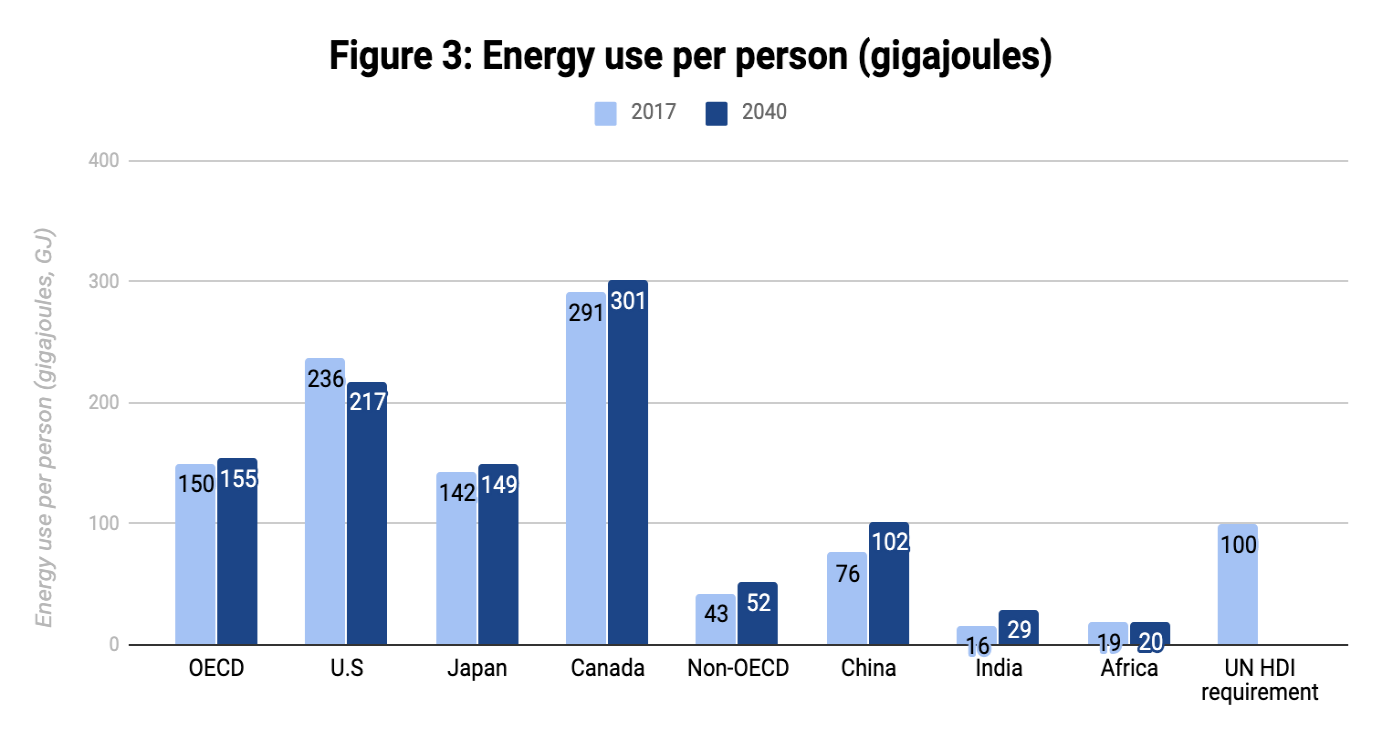

Beyond cycle normalisation, budget implementation remains a key challenge. Particularly, experience over the years reveal that the nation’s budget has consistently underperformed even when the budgets are passed into law early. The budgets have been described as ’incredible’ with the government’s inability to consistently and accurately meet both its revenue and expenditure targets. Looking at the budgets for the past eight years between 2011 and 2018 reveal that those for 2013 and 2015 were signed and passed into law in the first quarter of these years. In addition, the budget cycle for both years lasted for 15 months, which is more than the number of legislated months for a normal cycle. However, the budget implementation performance for these years are not quite different from other years when the budgets were passed much later (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Budget performance, cycle and date assented

Note: cycle indicates the number of months between the passage of current and succeeding years’ budget.

Source: National budget implementation reports 2011 – 2018

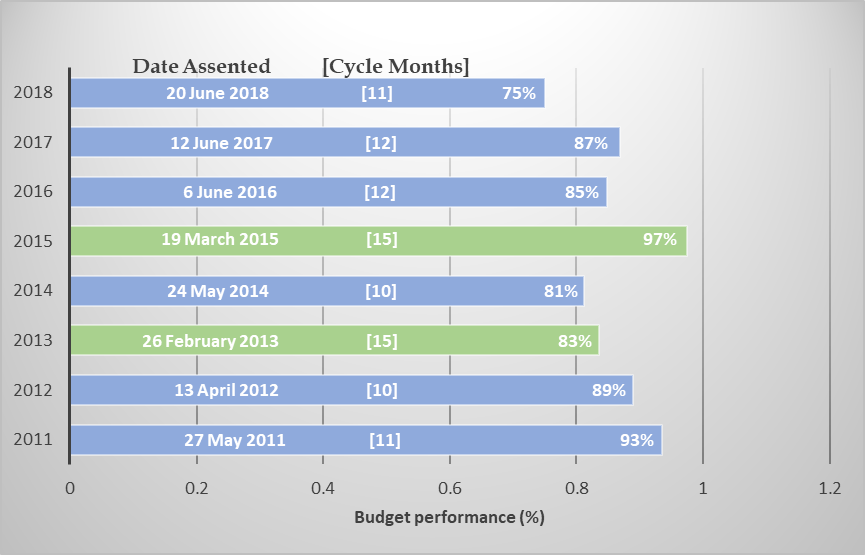

The biggest underperformance issues are on the capital side of the budget with most of the underspending related to capital expenditure. The average actual spending performance of recurrent expenditures against budgeted values between 2011 and 2018 stood at about 92.3%, while the capital is just around 62%. The degree of implementation of Nigeria’s capital spending clearly depict the inability to deliver on public services and achieve developmental objectives. Hence, meeting the nation’s commitments of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) could be an illusion since SDG action begins with credible budgets.

Figure 2: Capital and recurrent spending performance

Source: National budget implementation reports 2011 – 2018

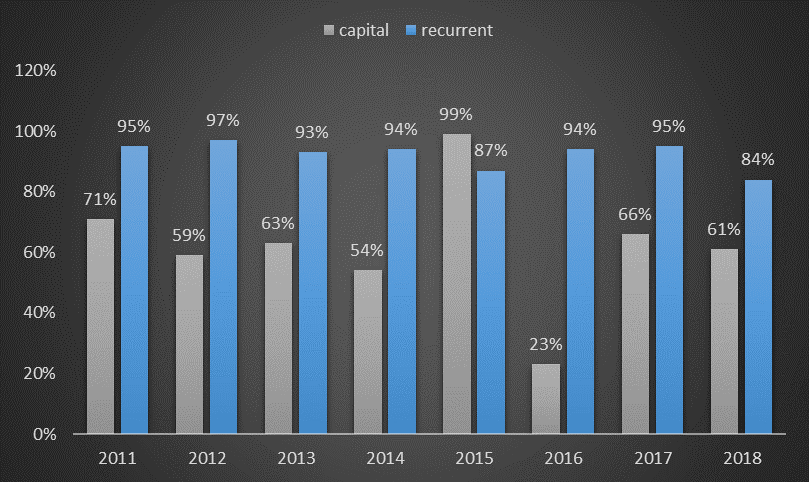

Over the years, the reason mainly explained for these underperformances is under-collection of oil revenue as a result of fluctuations in oil price or decline in oil production, and sometimes both. However, revenue performance between 2011 and 2018 reveals that oil revenue collections was about 78% over these years, with average difference of about 22% between the actual and budget projection. Further scrutiny reveals that the under collections of oil revenue were mainly as a result of poor production projections and not price variations. The Oil Price-Based Fiscal Rule (OPFR) which has been in operation since 2004 has ensured that volatilities in international crude oil price are curtailed by setting an oil price benchmark that is below the projected international rate (see Figure 3). Therefore, the problems associated with budget underperformance are explained by other factors.

Figure 3: Average annual oil price (actual versus budget estimate benchmark)

Source: National budget office and United States Energy Information Administration

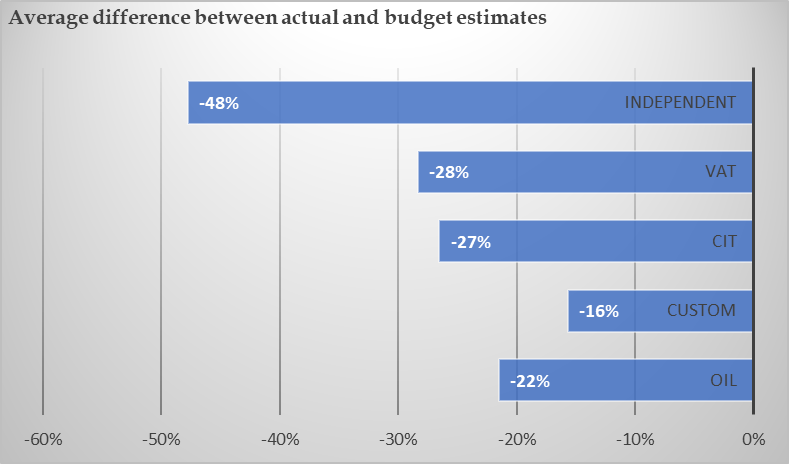

Underperformances of estimated revenue were mainly recorded in the non-oil revenue sources which include collections for Value Added Tax (VAT), Company Income Tax (CIT) and revenue from independent sources (Figure 4). The reasons for the underperformances of non-oil revenues could be that the revenue projections were high and unrealistic or there are leakages and non-remittances by revenue collectors. Others include are weak administrative and monitoring mechanisms, defective and bureaucratic procurement systems that often lead to unnecessary delay in capital spending, and weak legislative oversight among others.

Figure 4: Revenue collection underperformance (2011 – 2018)

Source: National budget implementation reports 2011 – 2018

Improving budget performance to achieve optimum implementation and thus achieve budget credibility requires a combination of different tasks and priorities. Some of these have been well documented in extant articles and literature. However, we attempt to reiterate some of these proposed solutions. First, the projections of revenue and expenditure should be targeted towards realisable estimates to ensure optimum performance. For example, the capital spending estimate for 2015 was reduced by about 50% from 2016 estimates. The capital expenditure performance recorded for that year stood at the record highest of 99%.

In addition, the introduction of a clear, concise and publicly accessible ex-ante and ex-post budget reports in addition to improved institutional coordination throughout the budgetary cycle, from conception to implementation, could enhance the credibility of the budget. Furthermore, synchronisation of published details of revenue and expenditure reports that capture actual against the budget that is consistent with international standards would further ensure performance monitoring, effective implementation and comparative analysis.

Finally, prevalence of unspent funds by Ministries, Agencies and Departments (MDAs) has further contributed to the implementation gaps in capital spending. Unspent and returned capital vote by MDAs have consequential implications on fiscal governance and performance of the budget, especially capital spending. Hence, the incidences of unspent budgets should be abated. Failure to implement budgets by MDAs, when funds are allocated and available, could be viewed as fraud and abdication of responsibility, and such should be treated accordingly.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China

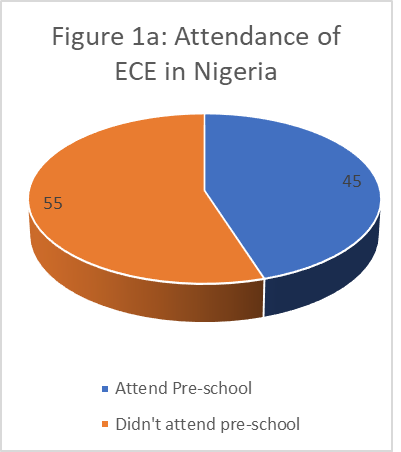

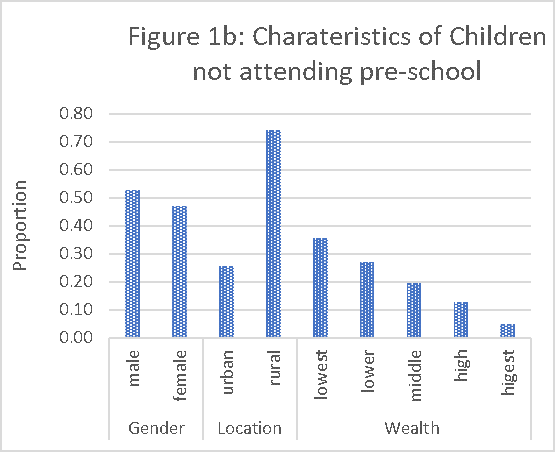

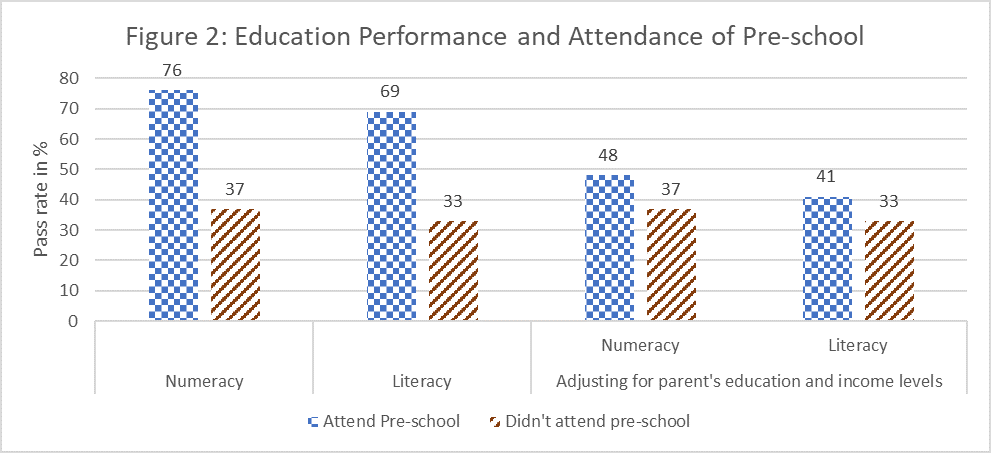

Source: Nigeria Education Survey (2015)

Source: Nigeria Education Survey (2015) Source: Nigeria Education Survey (2015)

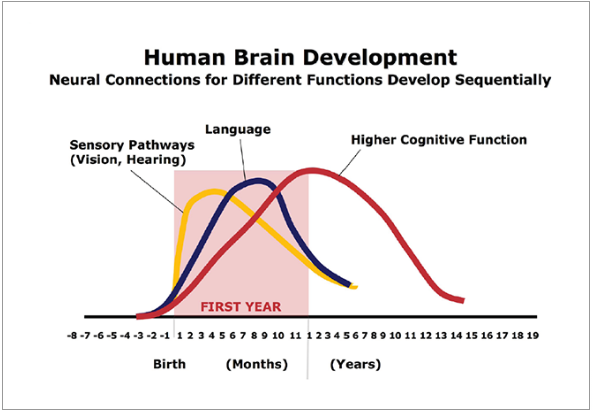

Source: Nigeria Education Survey (2015) Figure 3: Human Developmental Phases

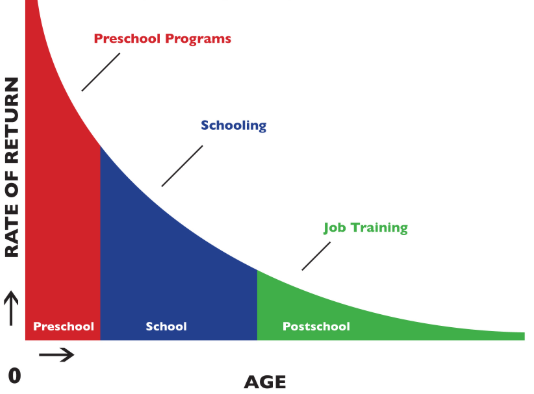

Figure 3: Human Developmental Phases Heckman curve

Heckman curve