CBN Cash-less Policy; A more impactful approach

Cashless economy involves transactions of economic activities using an electronic form of money for payment, rather than physical banknotes or coins1. It involves a painstaking gradual transition, rather than rushed transformation which can distort economic activities, lead to a sudden shortfall of cash, macroeconomic shocks and eventually slow down economic growth.

Benefits abound when economies operate with less cash given the pace of technology development and ongoing sophistication of the global financial system. Such development consolidates economic activities; by reducing the informal sector, it increases the precision of monetary policy on macroeconomic aggregates. Furthermore, the cash-less system reduces the cost of printing paper money, brings down transaction costs and risks, integrate the domestic economy with the outside world, increase the tax base, eliminate to some extent barriers to trade, and leads to financial inclusion amongst others. These have prompted some developing countries to explore the option despite lack of sustaining technologies.

Two countries, different approach

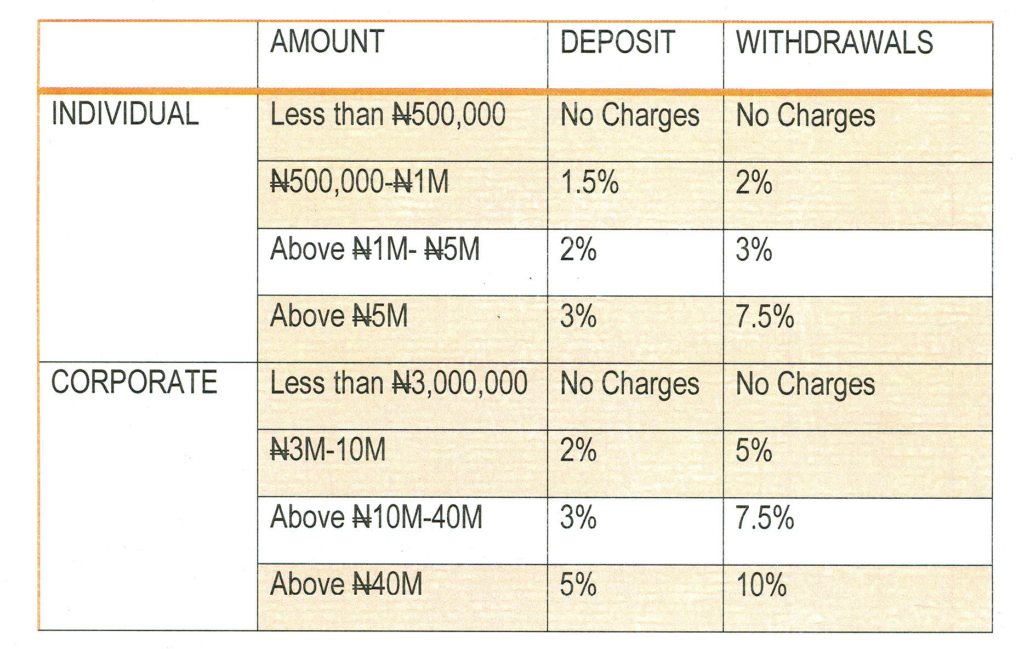

Lately, Nigeria and India have attempted to enforce the use of less cash in their economy. While Nigeria introduced fines on cash limit (table 1), India used demonetization. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) introduced the cash-less policy in 2012 with Lagos as a pilot state. The policy was extended to selected states in 2013, and nationwide by 2014.

Table 1: CBN Cash Limits & Charges

Source: CBN, 2017

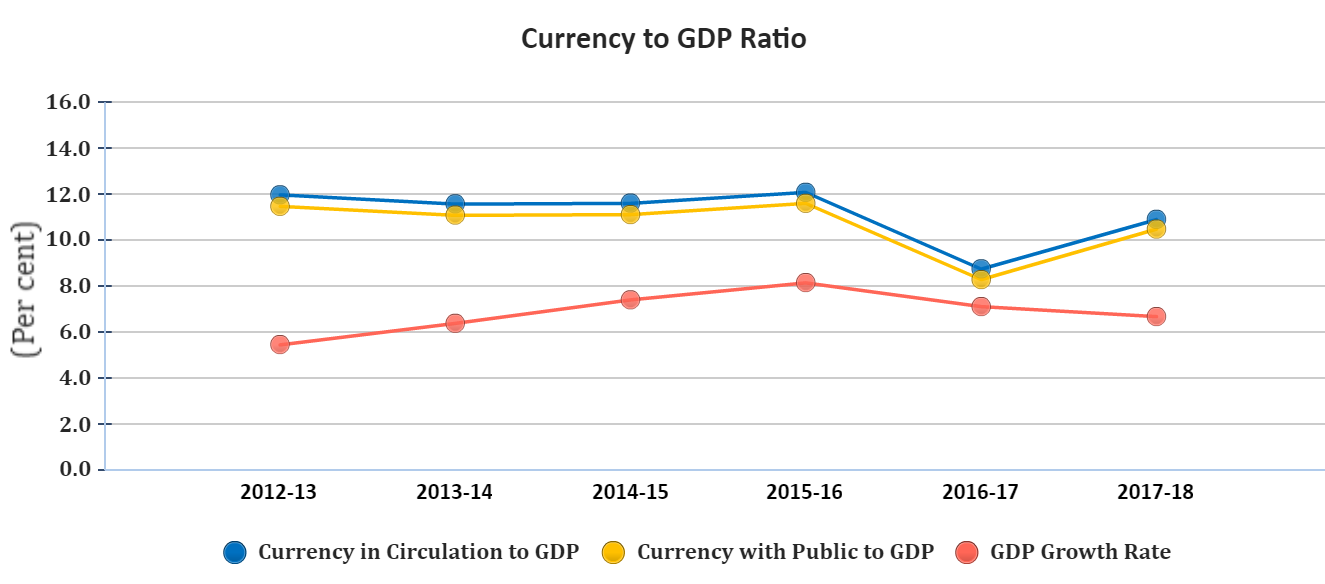

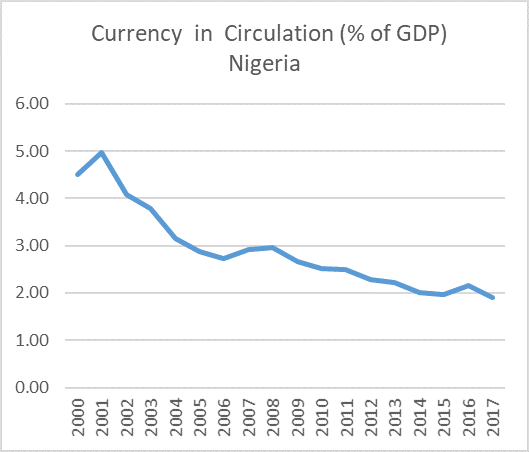

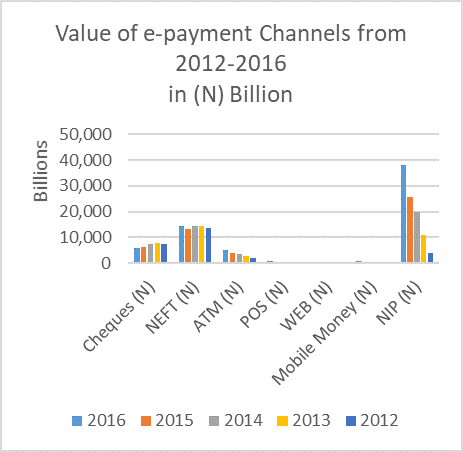

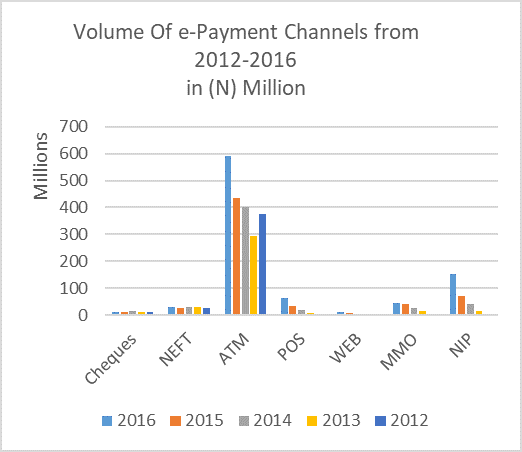

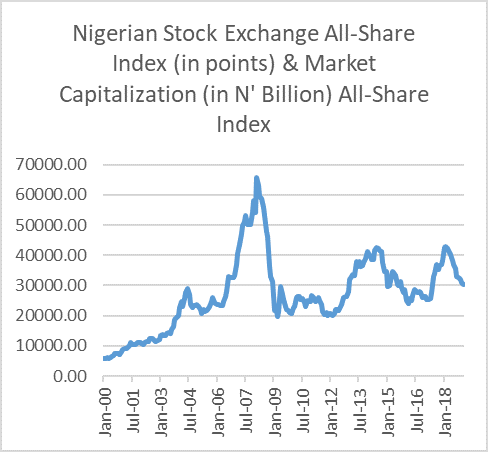

The policy took effect nationwide on April 1st 2017 and suspended 21 days later While currency in circulation (%GDP) fell, the objective of encouraging the use of e-payment has not been achieved as they are insignificant aside from NIP (NIBSS Instant Payment) Transfers (figure 2). On the other hand, the “Cash-less India” approach introduced in November 2016 scrapped the old high-value currency notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1000, withdrawing about 86 percent of the country’s currency in circulation and made available several channels of electronic payment system such as Banking Card, USSD, AEPS, UPI, Mobile Wallets, Prepaid Cards, POS, Internet Banking, mobile banking and Micro ATMs. Cash (% of GDP) fell from about 12% pre-demonetization to 8.8%.

Figure 1: India currency to GDP ratio

Source: Reserve Bank of India, 2018

Figure 2: Trend in selected macroeconomic and e-payment indicators for Nigeria economy

|

|

|

|

Source: CBN, NSE

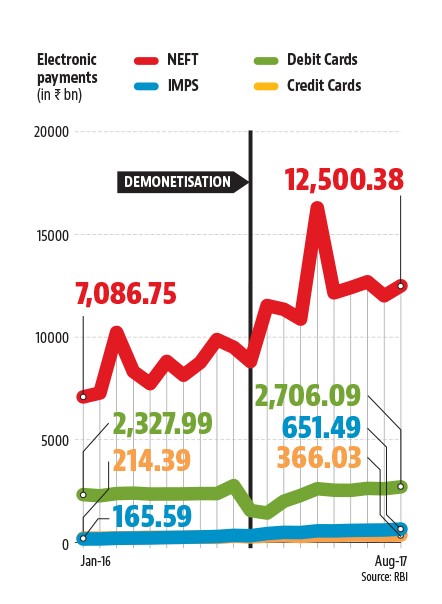

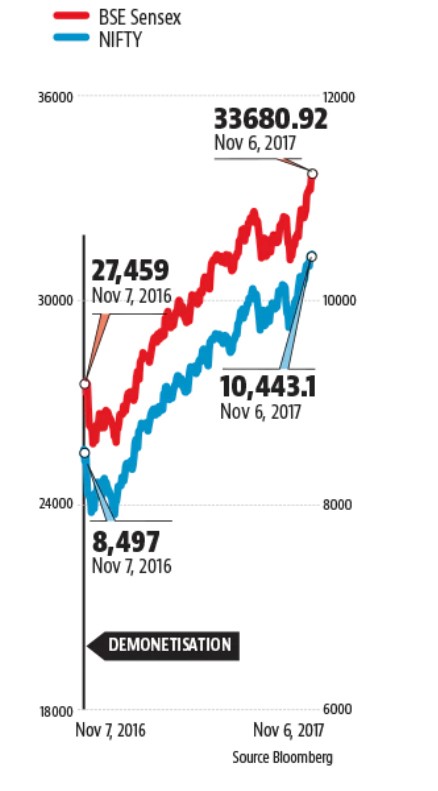

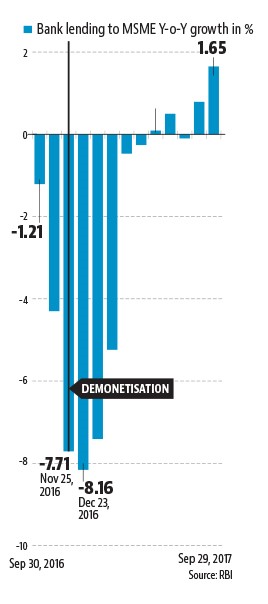

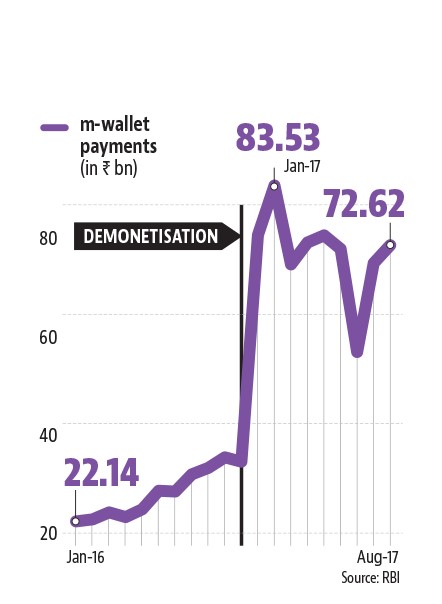

While the sudden shock slowed down growth from about 7.5% to 7.1% in January 2017, food (pulses) inflation dipped, the use of cash-less medium soared, the stock market responded positively and loans to MSME improved (figure 3).Figure 3: Impact of demonetization on India Economy.

Use of electronic payments |

Stock market |

Lending to MSME Source: mbauniverse, 2018

Source: mbauniverse, 2018 |

Use of mobile payments |

Non-liberal approach & Unfair Penalties-

Should the public be forced to undertake cash-free transaction through fines rather than nudging and making all the supporting infrastructure needed available? Who should be penalized when Banks’ ATMs are nonfunctional, leading its customers to withdraw from other Banks’ ATM? It is usually the customers! Who enjoys the proceeds of fines when bank electronic outlets fail forcing customers to do cash transaction and when customers lose money and time trying to resolve an unsuccessful electronic transaction? The processing fee goes to the CBN and Banks at a ratio of 40:60. Penalizing customers for a bank’s inadequacy, while such bank also enjoys from the proceeds of the “fines”, brings the question of fairness to regulatory policy. Rather than increase adoption rate, excessive penalties might as well increase the number of unbanked public. Efficiency and nudging in the right direction are what is needed.

CBN-Commercial Banks policy mismatch

While the CBN was pushing for mass use of electronic transactions, most banks view such as a way of extracting streams of charges from customers. Bank to bank cash transfer via the online medium, phone app or USSD come with charges, while walk-in cash transactions in banks are free. In this scenario, the only transaction cost to the customers, if they follow the cash-based walk-in transaction is time. More so, customers want to eliminate unnecessary frustration and time wasting trying to resolve an unsuccessful electronic transaction. This to most customers is more time consuming than cash-based walk-in transactions. This in itself is disincentive!

Social challenges

While CBN assumed that most Nigerians should be able to cope with cash-less transactions since they can use mobile phones, and engage in functions like recharging, PIN entry and SMS; about 91.8 million rural dwellers[1] and about 12.8.5 million elderly citizens were not adequately factored in the policy. This calibre of senior citizens still engages outsiders’ assistance when performing the listed functions. Hence, they are most highly susceptible to online frauds and loss of funds while trying to avoid the blanket cash transaction charges imposed by the regulator.

Workable Implementation Phases

Firstly, adequate awareness is crucial for the success of any policy. Sufficient and wider spread of information about the policy, training and demonstration on how to use several channels is needed, as well as making known the alternative electronic channels.

Secondly, the enabling Infrastructure, financial cyber protection and security should be invested on and put in place; Internet banking, the POS, mobile banking, mobile wallets, USSD, Micro ATMs, Pre-paid cards etc. Having several safe channels might capture the interest of the banking public to go cash-less and non-banking ones to come on board.

Thirdly, although the CBN took more of a bottom-up approach, there can be CBN-CAC-Banks collaboration. Through this, all incorporated organizations with CAC can be mandated to have at least two forms of electronic payments. With businesses falling in line, it would be easy for the public to follow suit, after all, they spend the cash by patronizing these businesses.

Fourthly, there should be real incentives for cash-less transactions. Not necessarily a reward-based, but the cost of cash dealing should be higher than Cash-less transactions, even for low-income earners; otherwise, it will not be attractive to the public. Therefore, the unnecessary and exorbitant online charges placed on Cash-less medium should be removed. Hence, rather than using expensive third-party platform for electronic transactions, CBN might need to set up its own and add more varieties of channels by working with NCC and the banks, whichever is cheaper.

In addition and most importantly, demonetization of higher Notes; Elimination of higher notes at least makes huge physical cash transaction uncomfortable, nudging the public towards the cashless transaction. This was India's approach- the country recorded successes both on the policy and on the macroeconomic aggregates- after some challenges caused by the abrupt removal of higher currency. Gradual demonetization with elongated time frame is therefore likely to be smooth.

Conclusion

Cash-less system has its enormous benefit on the macro-economy and is achievable if properly implemented. But it will be wise to nudge or allow the populace to go cash-less willingly while providing adequate, easy and secure channels of electronic payments.

[1] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=NG

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China