Is a debt crisis looming in Africa?

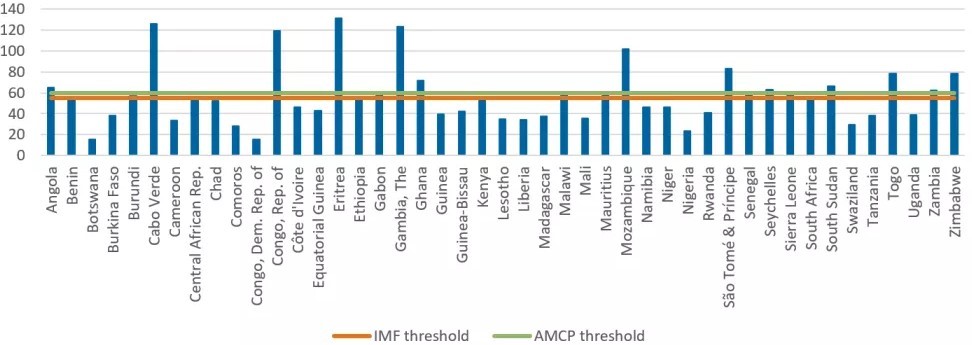

concerns about an impending debt crisis in Africa are rising alongside the region’s growing debt levels. As of 2017, 19 African countries have exceeded the 60 percent debt-to-GDP threshold set by the African Monetary Co-operation Program (AMCP) for developing economies, while 24 countries have surpassed the 55 percent debt-to-GDP ratio suggested by the International Monetary Fund. Surpassing this threshold means that these countries are highly vulnerable to economic changes and their governments have a reduced ability to provide support to the economy in the event of a recession.

While debt is a global issue, Africa’s past debt crises have been devastating, creating the need to cautiously monitor this recent debt buildup. There are parallels between the present rising debt in Africa and the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative period that proffer solutions for prevent another crisis.

Figure 1: Government debt as a percent of GDP for African countries, 2017

Source: IMF, 2018. Regional Economic Outlook

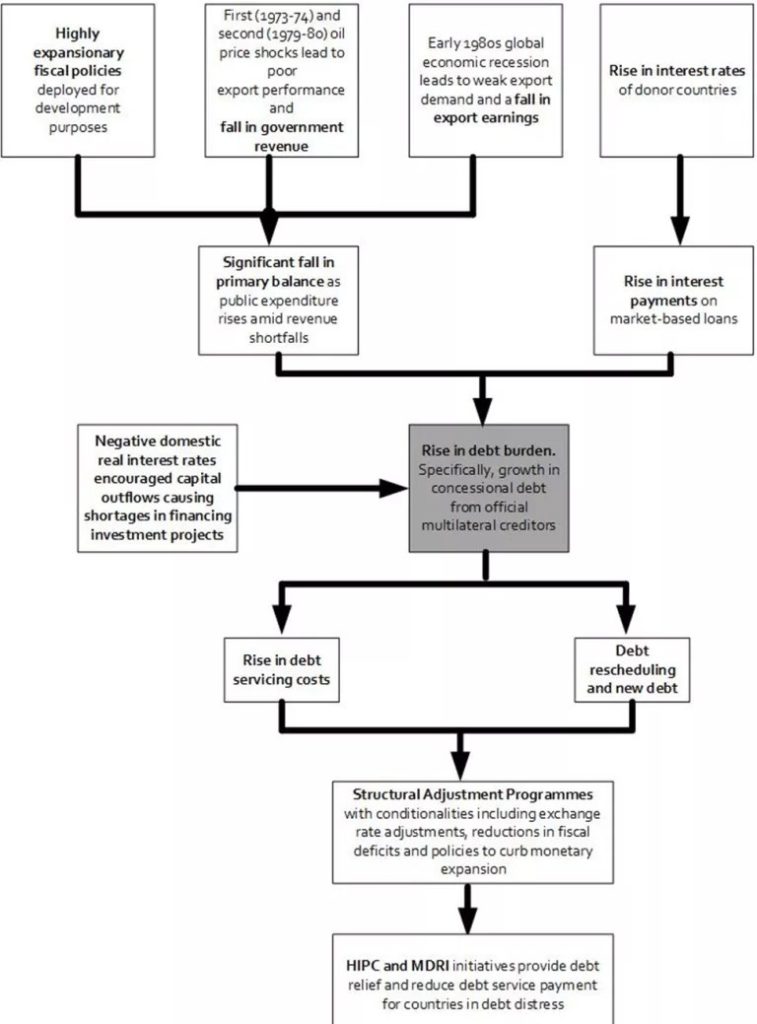

The events that led to HIPC and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) started in the 1960s from a public spending spree by recently independent countries to stimulate their economies through rapid investment in industry and infrastructure projects (Figure 2). Commodity booms and heavy use of external debt supported this spending as policy leaders relied on future export earnings and economic growth to improve the capacity to service the debt. Notably, those countries did not reduce expenditures during negative commodity shocks and instead took on more loans.Three key factors drove the subsequent debt crisis—the 1980s global recession, the rise in interest rates in developed countries, and a decline in real net capital inflows, which was largely due to the real negative interest rate in many countries.

As a result, the external debt-to-gross national income (GNI) ratio for the continent rose from 49 percent in 1980 to 104 percent in 1987. The World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Program attempted to tackle the problems by reducing fiscal deficits through expenditure cuts, but these austerity measures had severe, adverse impacts on social spending (and thus on livelihoods), and resulted in large current account deficits, astronomical inflation, and depressed currencies. This situation led the World Bank and the IMF to establish the HIPC initiative in 1996 to provide debt relief and reduce debt service payments of up to 80 percent for eligible countries.

Figure 2. Description of events leading to Africa’s indebtedness in the 1970s and early 1980s

In addition, in 2005 the IMF initiated the MDRI, which provided full debt relief on eligible debt. Under HIPC and MDRI, 36 countries, including 30 African ones, reached the completion point (the phase at which total debt relief is received) resulting in debt relief of $99 billion by the end of 2017. Between 1999 and 2008 alone, HIPC and MDRI reduced the external debt-to-GNI ratio for the region from 119 percent to 45 percent.

IS AFRICA HEADING BACK TO THE HIPC ERA?

Not quite…but the present composition of debt is worrisome.

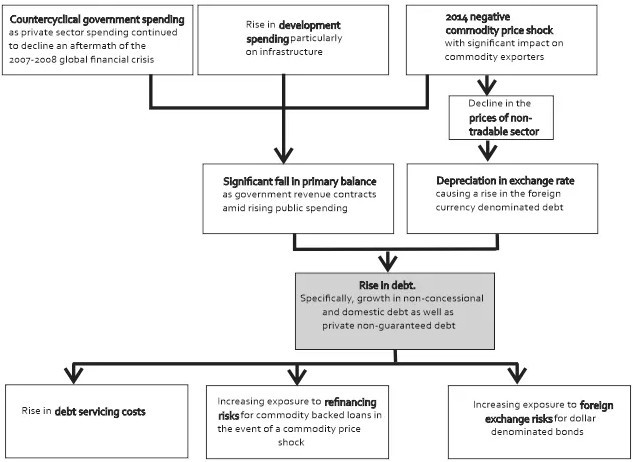

The drivers of the present rising debt situation are similar to, but not the same as, that of the HIPC era (see Figure 3). In the wake of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, governments deployed countercyclical spending to compensate for depressed private sector spending.

Another key driver was the huge rise in public expenditure on infrastructure—an effort to close the huge infrastructure gap (Africa needs to spend $93 billion annually from 2009 to 2020 to close its infrastructure gap).Of greatest magnitude was the 2014 negative commodity price shock, which dramatically reduced government revenues.

Figure 3. Description of events leading to the present debt situation

The aforementioned factors led to a decline in primary balance from 3.9 percent of GDP between 2006 and 2008 to -6.9 percent of GDP by 2015 with countries borrowing excessively to meet public expenditure. The commodity price shock caused a depreciation in the exchange rate for several countries. Following the depreciation, foreign currency- denominated debt increased significantly.

A distinctive feature of the ongoing rising debt problem is the composition of debt. Countries are tilting away from official multilateral creditors who come with stringent conditions and toward non-concessional debt with relatively higher interest rates and lower maturities. This trend raises concerns around debt sustainability given the possibility of higher refinancing risks—particularly for commodity-backed loans in the event of a commodity price shock—and foreign exchange risks.

Furthermore, private non-guaranteed debt has grown: Between 2006 and 2017, private sector external loans tripled from $35 billion to $110 billion. This growth could result in a balance of payment problems as the private sector competes with the public sector for foreign exchange. Also, it may increase the government’s exposure to risks associated with contingent liabilities in the event of a default.

Another noteworthy trend is that countries witnessing a deepening of their financial markets are increasingly borrowing from their domestic debt market. South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria, among others, have been issuing long-term bonds for large capital projects such as roads and hospitals. While tapping into the domestic debt market provides a sound alternative and does not expose the country to foreign exchange risk, it has the potential to crowd out private sector borrowing, thus hampering investment and output growth.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

The rising debt burden across the continent is clearly a concern for borrowers, lenders, and the broader international community. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the present debt level is far below that of the HIPC era: In 2017, public debt as a percent of GDP in sub-Saharan Africa was 45.9 percent relative to the 117 percent external debt-to- GNI ratio of 1995. Also noteworthy is that sovereign debt financing is inevitable given that African countries budgetary resources are insufficient to finance their vast development agenda. Thus, in ensuring that all stakeholders become more prudent, we recommend the following:

1. Better debt management

Despite the spike in sovereign borrowing, sub-Saharan Africa’s performance in debt management has consistently declined from 3.34 in 2014 to 3.08 in 2017 (on a rating scale from 1 to 6). For those without, authorities need to design and implement formal and legal frameworks for debt management that stipulate borrowing targets and preferences for borrowing sources. Countries can tap into the support programs provided by the IMF and the World Bank. Also, establishing systems and processes to ensure up-to-date debt recording and timely debt service payments is necessary for maintaining accountability,

transparency, and sustainable debt levels. With the characteristics of debt changing significantly (e.g., the rise of nontraditional lenders, growth in domestic debt, an increase in private nonguaranteed debt), debt management authorities must utilize more sophisticated means to better analyze the costs and risks of these changes. Overall, these sound debt management practices should be extended to the subnational level and state-owned enterprises to ensure more comprehensive management.

2. The issuance of “debt-management” financial instruments

Local authorities should issue debt instruments that can better manage the debt level. For instance, the issuance of the sukuk bond— Islamic bonds that allow investors to generate returns by having a share in the ownership of the asset linked to the investment rather than earning interest from the bond—that is tied to capital projects in Nigeria curtail the improper use of debt. Also, they should consider a state-contingent debt instrument that links debt service to predefined macroeconomic variables, such as GDP growth and changes in commodity prices. Thus, shocks that negatively impact fiscal space, such as economic recession, will not increase the debt service burden of the issuing country.

3. More responsible lending

A debt crisis poses risks to borrowers and lenders alike. For this reason, lenders should focus on making more responsible lending decisions following due process in authorizing loans and possibly stipulating limits. Presently, the codes of conduct that address irresponsible lending such as the G-20’s Operational Guidelines for Sustainable Financing (2017) and the OECD’s Recommendation on Sustainable Lending Practices and Officially Supported Exports Credits (2018) are only binding on traditional creditors. A first step should be the development of new codes or a revision of existing ones to adjust to nontraditional actors. In addition, these codes should be enshrined in law so that participating countries adhere to them. Better coordination, more engagement, and increased information-sharing between traditional and nontraditional lenders is also crucial.

4. Streamlining procedures

The World Bank and IMF impose numerous, stringent, and time-consuming conditions on developing countries in order to access development finance, many of which advocate for controversial reforms such as privatization and trade liberalization policies that are not in accordance with the will of the developing country. Streamlining the lending process to reduce the number and scope of conditions to respect national sovereignty and reduce the burden associated with accessing loans is of the utmost importance. The World Bank could also increase the lending program to middle-income countries that still face development challenges like inequality, unplanned urbanization, and a weak private sector. Better engagement with these countries will enable them to consolidate their development gains and make substantial economic and social progress.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China

This Memo was drafted in collaboration with

This Memo was drafted in collaboration with