Learning trajectories are graphs that show how many children achieve a certain level of minimum proficiency at each grade. While learning trajectories have previously been used for research, two new efforts show that they can also serve as practical tools to analyse the learning crisis and take informed action.

First, the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Programme, in partnership with the GEM Report, have created a webpage offering a one-stop resource on learning trajectories. This webpage introduces learning trajectories and what they offer through a series of interactive data visualisations and a data explorer which allows users to build and analyse their own learning trajectories. Second, RISE and the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa (CSEA) have partnered to train around 75 policymakers and government officials in West Africa on the use of learning trajectories for informed policymaking.

This article was written by Rastee Chaudhry, Jason Silberstein, and Julius Atuhurra (RISE Programme) and Adedeji Adeniran, Thelma Obiakor, and Sixtus Onyekwere (Centre for the Study of the Economies in Africa)

The proposed 2023 budget Bill was presented on October 07, 2022. While presenting the budget, President Muhammadu Buhari highlighted the revenue challenge, which may have influenced the size of the budget. This article uses nine charts to highlight the 2023 budget in relation to the amended 2022 budget at the aggregate level. In terms of expenditure size, the 2023 budget is higher than the 2022 budget

Not all elements of expenditure increased; expenditure items relating to productive investment, such as capital expenditure and statutory transfers, were reduced, whereas recurrent expenditure and debt services that had limited impacts on the future growth outlook were increased.

In contrast to expenditure, the proposed revenue for the 2023 fiscal year was reduced in comparison to the amended budget for 2022. The revenue decline reflected challenges in crude oil production and weak revenue mobilisation. The following section provides a detailed breakdown of the 2023 budget.

Overview of the 2023 Budget

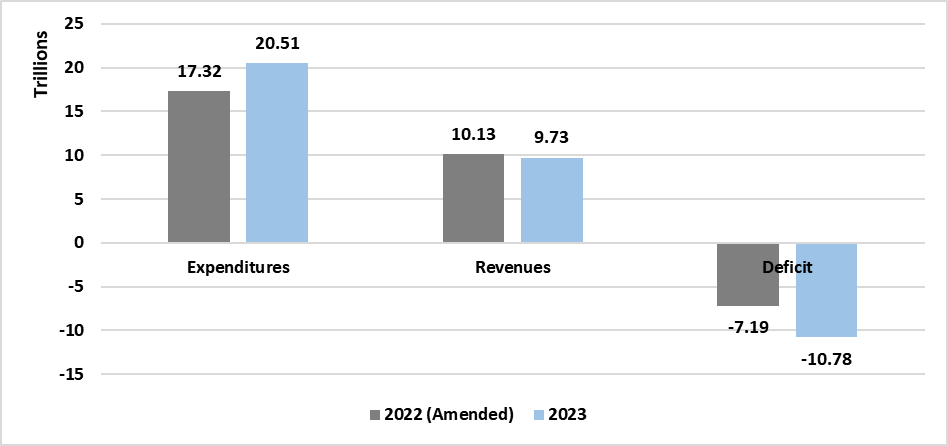

In the 2023 proposed budget, the total expenditure is N20.53 trillion, which is approximately N770 billion more than the N19.76 trillion in the approved Medium Term Expenditure Framework and N17.32 trillion in the 2022 amended budget. The increase in expenditure might be argued to be consistent with the rising prices. However, total revenue in the proposed budget for 2023, fell to N9.73 trillion from N10.13 trillion in the amended budget for 2022. As a result, the budget deficit increased to N10.78 trillion from N7.19 trillion in the 2022 amended budget. This indicates that the rising price level had an increasing effect on the expenditure side while decreasing the revenue outlook of the government. Based on the historical trend of revenue underperforming relative to expenditure as seen in the first quarter of 2022, government borrowing at the end of 2023 is very likely to exceed N10.78 trillion. However, the extent to which the government may borrow, particularly external borrowing, will depend on the interest rate in the international market. If the government is unable to borrow as anticipated, expenditure rationing would be predominant in the next fiscal year.

Figure 1: Aggregate Expenditure and Revenue

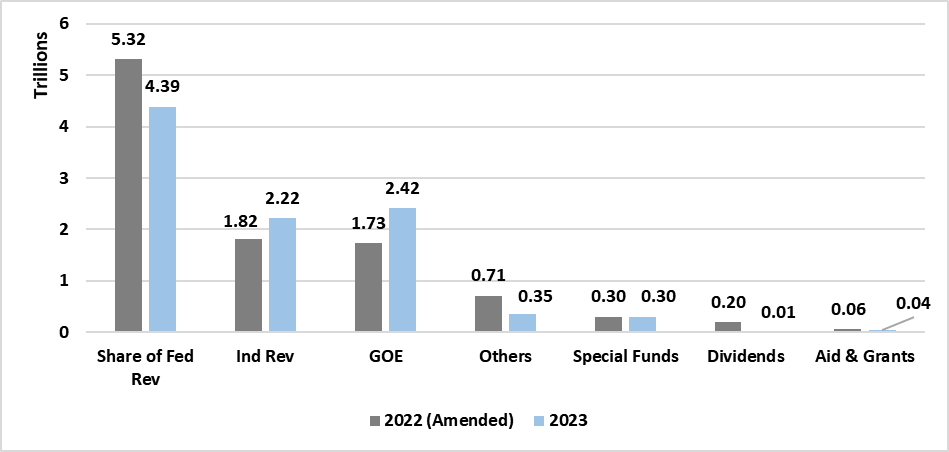

The breakdown of the revenue is shown in Figure 2. The revenue element has seven main categories, and only two items were increased in the proposed 2023 budget compared to the 2022 budget - independent revenues and government-owned enterprise. The government retained the values of special funds and lowered other revenue items such as share of federal revenues, dividends, aid and grants, among others.

The share of federal revenues was cut from N5.32 trillion in the 2022 budget to N4.39 trillion in the proposed budget. On the positive side, the government increased independent revenue from N1.82 trillion in the amended 2022 budget to N2.22 trillion in the proposed budget. Similarly, revenue from government-owned enterprises (GOE) from N1.73 trillion in the amended 2022 budget to N2.42 trillion in the proposed budget. The historical performance of GOEs makes one sceptical of potential revenue from the GOEs in the next fiscal year.

The assumptions that underline crude oil production and prices appear optimistic, especially crude oil production. The benchmark price of crude oil is $70 per barrel and crude oil production is 1.69 million barrels per day (mbpd). Without bold initiatives to reverse the decrease in crude oil production in the past few years, crude oil production in the next fiscal year is likely to be lower than the projected level of 1.69 mbpd. In the third quarter of 2022, Nigeria’s daily crude oil production was an average of 1 trillion mbpd, which is a 23.1 percent decrease from 1.3 mbpd recorded in the first quarter of 2022. The assumed production level in the 2023 budget, which is lower than the OPEC quota of about 1.8 mbpd but slightly higher than the assumption of 1.60 mbpd in the 2022 amended budget seems too high based on the current production level. With the projected low global demand in the next fiscal year and the contribution of high energy prices to the rising price levels, there is a high possibility that crude oil prices might fall below the $70 per barrel assumed in the next fiscal year. Overall, there is an urgent need to overhaul the revenue strategies, especially the GOEs, to attain the revenue projection of N9.73 trillion.

Figure 2: Revenue Breakdown

Notes: Share of Fed Rev denotes the share of federal revenues; Ind Rev denotes independent revenues; GOE denotes government-owned enterprises.

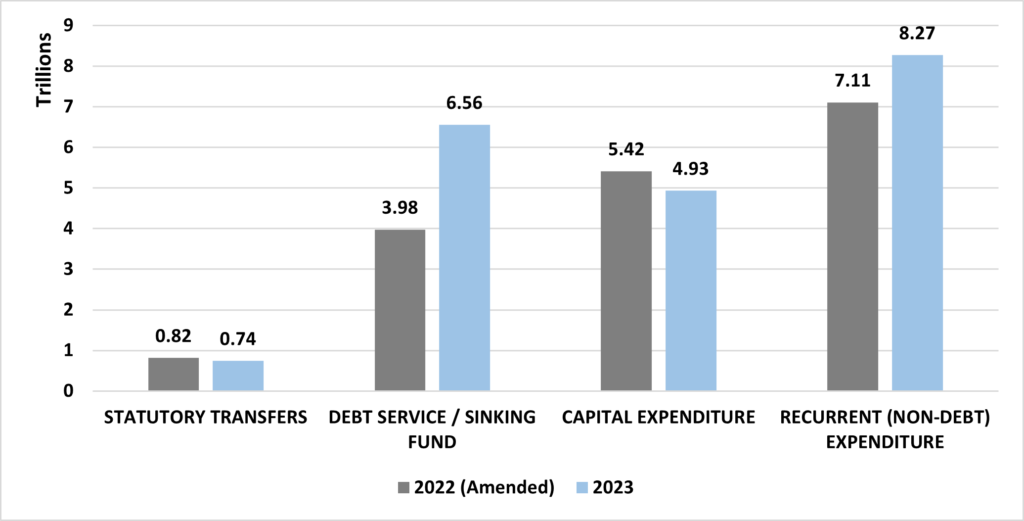

Next is the expenditure side. Government expenditure is broadly grouped into four categories: (i) statutory transfers, (ii) debt service and sinking fund, (iii) capital expenditure, and (iv) recurrent non-debt expenditure. Figure 3 shows that without adjusting for inflation, non-debt recurrent expenditure and debt services increased whereas statutory transfer and capital expenditures were reduced in the proposed 2023 budget relative to the 2022 amended budget. The Statutory transfers and capital expenditure were reduced by about N73.6 billion and 480.9 billion, respectively, making a total of N554 billion. In contrast, debt service and recurrent non-debt expenditure increased by about N2.58 trillion and N1.16 trillion, respectively, making a total of N3.74 trillion. However, the magnitude of the latter (N3.74 trillion) is higher than the former (N554 billion), resulting in an increase in government spending in the proposed budget by about N3.19 billion. The analysis suggests that the increment in the proposed budget is not driven by productive expenditure items, which are critical in enhancing a nation's competitiveness and productive capacity, casting doubt on the country's future growth and development.

Figure 3: Sources of changes in aggregate expenditure

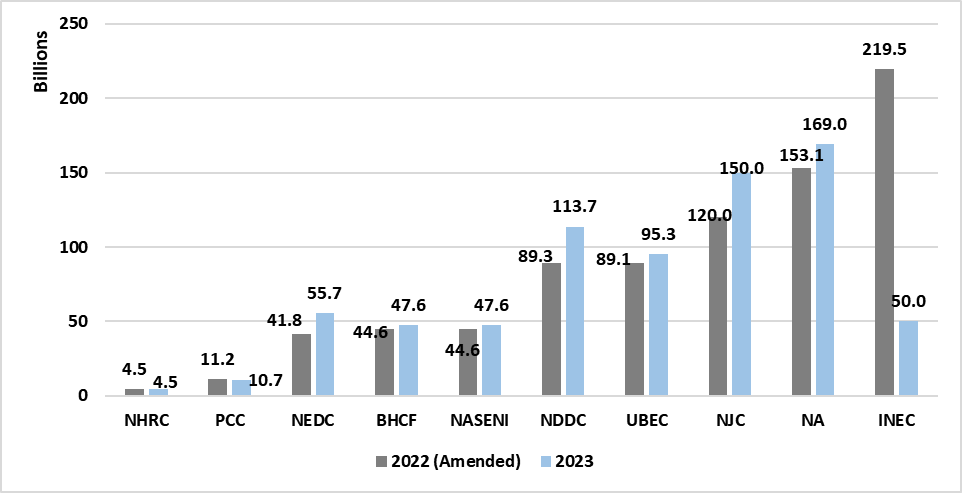

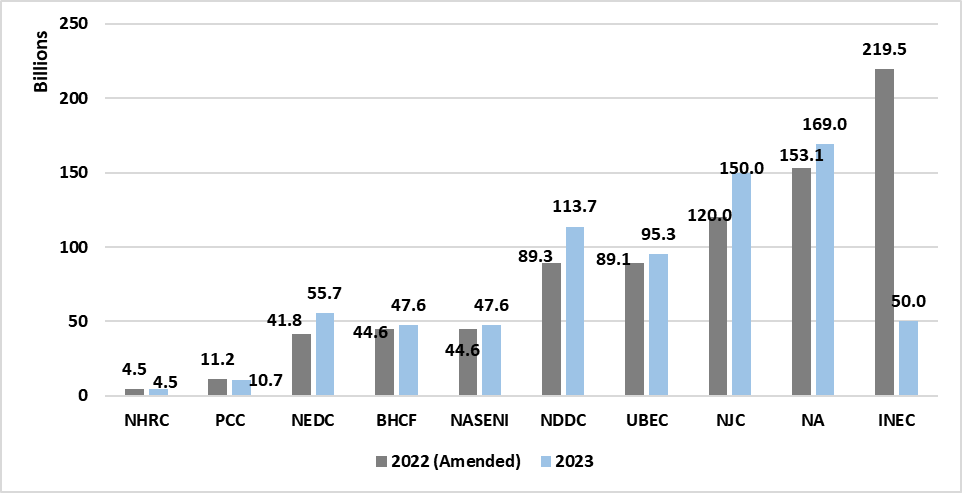

Statutory transfers are funds apportioned to government institutions that do not receive direct funding from the executive due to the nature of their functions. Currently, ten institutions receive funding through the statutory transfers depicted in Figure 4. The year-on-year decrease in the proposed budget is driven by the cut in two institutions (Public Complaints Commission (PCC), and Independent Electoral Commission (INEC)). For instance, the budgetary allocation to INEC in the proposed budget is N50 billion, which is about a quarter of the amount budgeted in 2022. The sharp decline in INEC exceeds the increase in the other statutory transfer items that increased.

Figure 4: Composition of statutory transfer

Notes: NHRC is the National Human Rights Commission; PCC is the Public Complaints Commission; NEDC is the Niger-Delta Development Commission; BHCF is Basic Health Care Fund; NASENI is National Agency for Science and Engineering Infrastructure; NDDC is Niger-Delta Development Commission; UBEC is Universal Basic Education; NJC is National Judicial Council; NA is National Assembly; INEC is Independent Electoral Commission.

Every fiscal year, the government appropriates funds to ensure the timely payment of loan interest and principal. Nigeria's debt service is divided into two categories: domestic debt service and foreign debt service. Budgetary allocations for both domestic and foreign debt services were increased in the proposed budget relative to the amount stipulated in the 2022 amended budget, as shown in Figure 5. The increase implies that the limited government revenue would be used to service the debt. Domestic debt service was increased by 75% to N4.5 trillion in the proposed budget, while foreign debt service was increased by 62% to N1.8 billion.

However, the sinking fund was decreased by 15 percent to N247.7 billion. As a result, the amount allocated for sinking funds and debt service stood at N6.56 trillion and 67.4 percent of the proposed revenue. Of the N3.19 trillion increase in total expenditure, debt services accounted for about 80.9 percent of the increase. Given that budgeted debt service is usually higher than actual, whereas budgeted revenue is less than actual, debt service as a ratio of government revenue might exceed 100 percent.

Figure 5: Proposed 2023 budget: Rising sinking fund and debt service

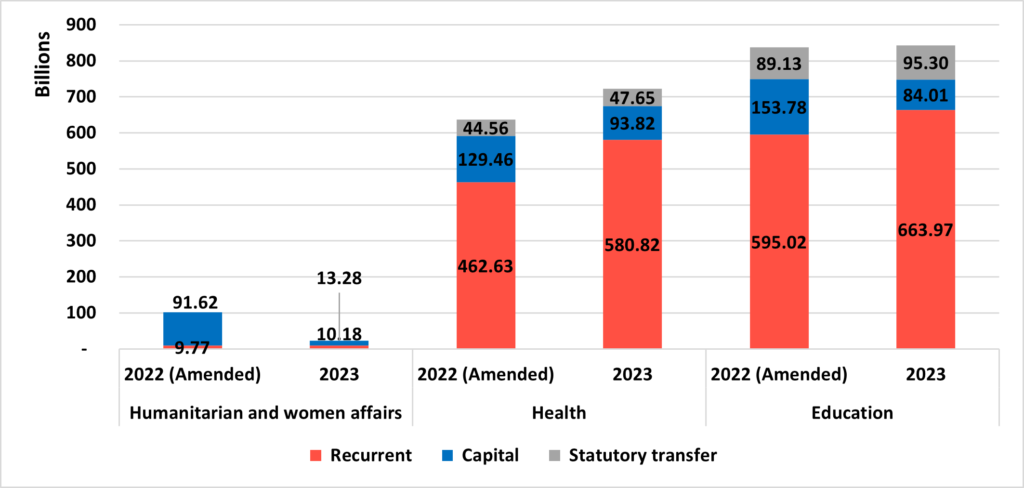

Budgetary allocation to critical economic sectors is examined in the following four charts. In Figure 6, we presented information about humanitarian and women’s affairs, health, and education. Adequate budgetary allocations, especially capital expenditure, to these sectors, are essential in having enlightened citizens in good health. In the proposed 2023 budget, it is evident that all the sectors recorded a decrease in capital expenditure, reducing the ratio of capital expenditure to recurrent expenditure. However, the recurrent expenditure increased in all the sectors. The increase in recurrent expenditure for both the health and education sectors exceeded the cut in capital expenditure. The increase in the education sector’s recurrent expenditure is partly consistent with the recent upward review in the retirement age (to 65 years) and elongation of service years (to 40 years) for teachers in the Harmonised retirement age for teachers in Nigeria Act. The decrease in the ratio of capital expenditure to total expenditure for the social sector indicates that actors in the sector would be faced with situations of working with old and ageing equipment with no hope of replacement. Also, newly developed modern pieces of equipment are less likely to be acquired, which ought to enhance their productivity.

For example, doctors are more likely to be denied access to new w surgical tools that could make them attend to more patients in a day, which in turn, would increase patients waiting time in hospitals. Furthermore, the low budgetary allocation for teachers indicates that teachers in unity schools are less likely to have access to the most up-to-date digital teaching tools.

Figure 6: Social sector

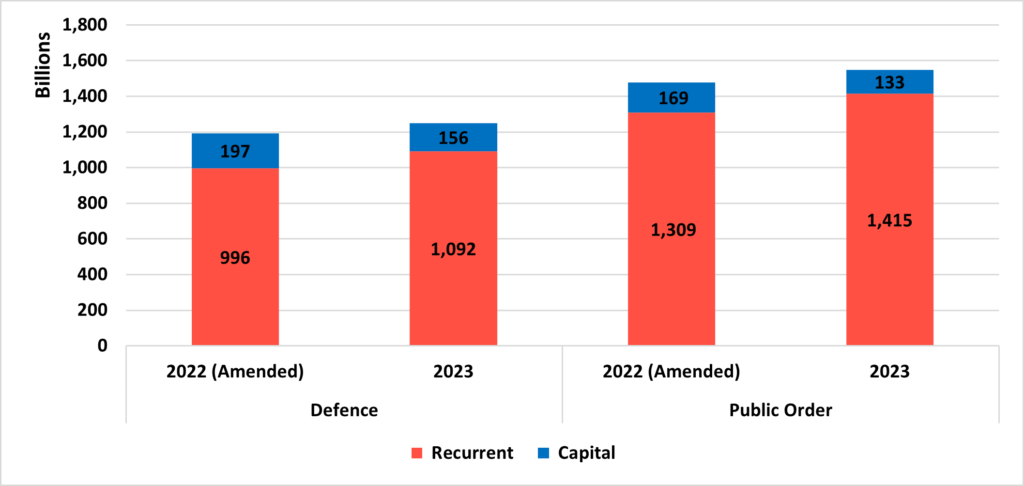

Nigeria is dealing with insecurity, which to a large extent, has limited the economy's rate of expansion. The proposed budget for security in 2023, depicted in Figure 7, provides guidance on how the government will address insecurity. The allocation to defence and public order mirrors what was previously observed in the education and health sector, where less than a quarter of budgetary allocation was assigned to capital spending. In the proposed budget, capital spending was reduced for both defence and public order, whereas the recurrent expenditure was increased. The pattern is like what was earlier reported for the aggregate expenditure. The public order consists of the Ministry of Interior, the Office of the National Security Adviser, the Federal Ministry of Justice, Police Services, the Federal Ministry of Police, the National Judicial Council, and the Police Service Commission. A source of concern here is that an economy with an upcoming election year that has been characterized by uncertainties and embroiled with high insecurity should prioritise spending on capital expenditure for security agencies in 2023 to facilitate investment in modern-day equipment and strengthen intelligence gathering to effectively protect lives and properties.

Figure 7: Defence and public order

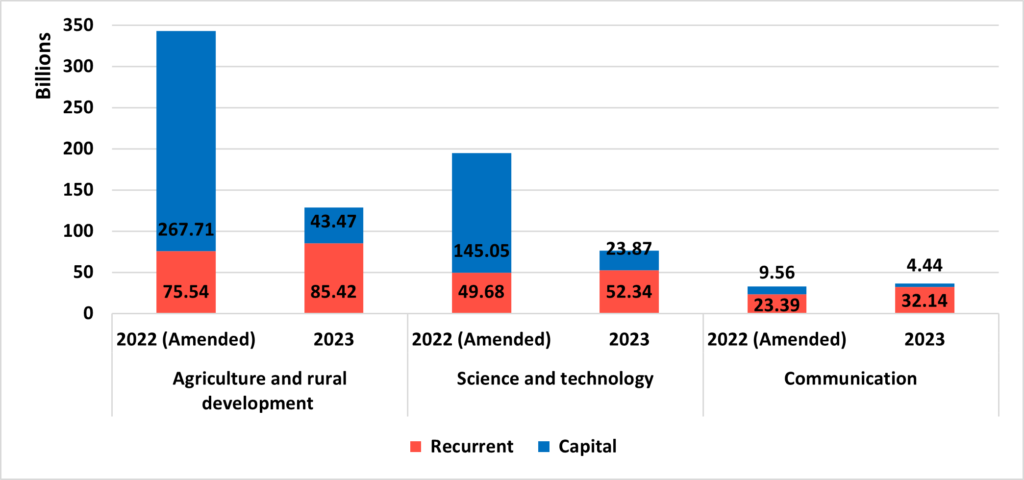

Nigeria is an agrarian society with agriculture accounting for more than a quarter of the domestic output and employing more than a third of the labour force, especially in rural areas. As the economy advances and with the emergence of new industries, the share of employment in agriculture is decreasing. The disruption associated with the pandemic is projected to increase the transition away from agriculture as technological space expands. The extent to which an economy would develop depends mainly on investment in science and technology, including communication. In the proposed 2023 budget, the allocation to Science and Technology decreased by N118.5 billion to N76.2 billion from N194.7 billion in the 2022 amended budget. The decrease was mainly driven by the cut in capital expenditure which declined by about N121.2 billion to N23.9 billion in the proposed budget. Further, the government reduced capital expenditure allocation for agriculture and rural development and communication. As a result, in these sectors, the ratio of capital expenditure to total expenditure decreased by about half. The ratio decreased from 78 percent in the 2022 amended budget for agricultural and rural development to 33.7 percent in the proposed 2023 budget. Similarly, for the communication sector, the ratio decreased from 29 percent in the 2022 amended budget to 12 percent in the proposed 2023 budget.

Figure 8: Enabling sectors: Agriculture, Communication and Science

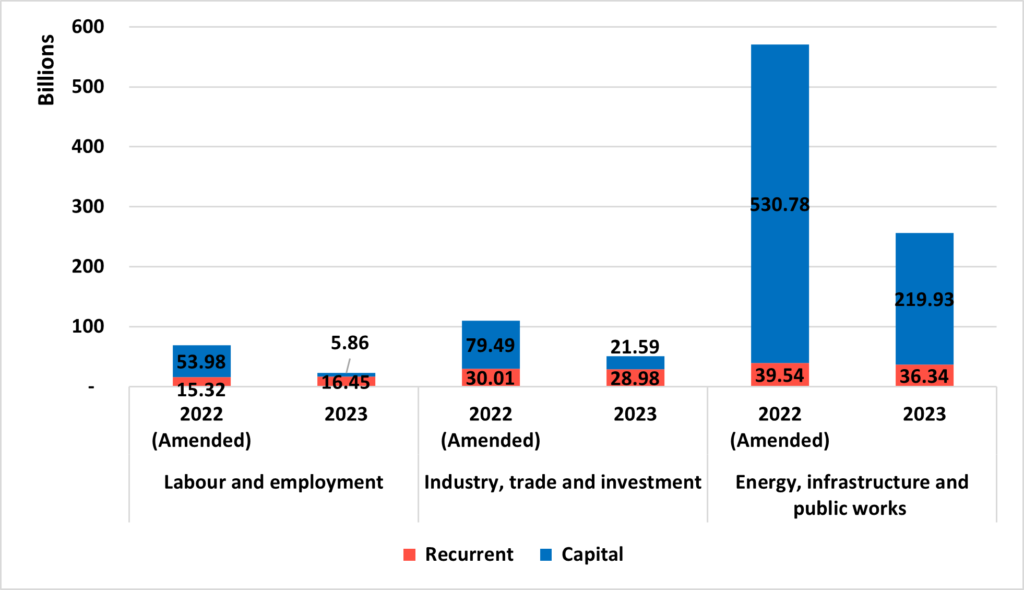

The potential growth of an economy is informed by labour and capital investment. Figure 9 shows proposed budgetary allocation to (i) labour and employment; (ii) industry, trade, and investment; and (iii) energy, infrastructure, and public works in the 2023 fiscal year. Unlike the pattern observed for social sectors and defence and public order, allocation to recurrent and capital expenditure decreased in (i) industry, trade, and investment; and (ii) energy, infrastructure, and public works. The decrease in budgetary allocation to these sectors in the face of rising price levels indicates that limited projects might be executed in the 2023 fiscal year compared to 2022. Also, the government may not be able to execute enough projects that are critical to starting industrialisation necessary to create jobs and reduce poverty, as envisioned in the Medium-Term National Development Plan, 2021 – 2025.

Figure 9: Engine of growth: Labour, Investment, and Infrastructure

Implications

The 2023 proposed budget has two key implications for the 2023 fiscal year:

Conclusion

This article highlights how imperative it is for the government to effectively mobilize all available revenue sources; otherwise, more than half of the 2023 budget will be financed through high-interest-rate borrowing, increasing future debt service. Furthermore, to realize the federal government's investment commitment in the National Development Plan, budgetary allocation for capital expenditure must be significantly increased in 2023 and beyond. Hence, in the deliberation and preparation of the implementation framework for the 2023 budget, due consideration should be given to two keys: (i) revenue mobilisation and debt management and (ii) performance of capital expenditure and incentivization of the private sector participation in the provision of infrastructure.

COVID-19 has compounded a long-standing learning crisis in many African countries, where millions of children were already out of school before the pandemic.

Nigeria has the highest rate of out-of-school children, low literacy rates, and high inequalities between and within groups in terms of education access and learning outcomes. The pandemic further reduced school attendance by approximately 17%, particularly among adolescents aged 15 to 18, according to a working paper by Dessy et al. For many school-aged children, temporary school closures have become permanent.

Meanwhile, evidence suggests about half a year’s worth of learning loss on average across the country. In other African countries with data, the learning loss ranges from eight months (South Africa) to two years (Uganda).

New thinking and innovations are required to rebuild Nigeria’s education system. Based on our research and practice in the sector, we have pinpointed five ways in which Nigeria’s education sector can achieve an inclusive recovery from the pandemic:

The pandemic has disproportionately affected the most marginalised groups, and many are at risk of long-term exclusion. Many children who no longer attend school are from poorer backgrounds and reside in rural or remote areas. Technology to mitigate learning loss during the pandemic was often inaccessible to rural communities because of lack of electricity or internet connectivity as well as other financial or logistical constraints.

It is critical to prioritise the needs of the most vulnerable children because they are likely to require the most investment to recover from learning losses. At a time when state budgets are strained, a resource-efficient way to achieve this is to collaborate with grassroots organisations that support the most vulnerable communities at a local level.

Data for performance monitoring and evidence-based research was critical to Nigeria’s policy response during COVID-19. School closures, remote learning programmes, and school reopening were all guided by evidence. Most studies that tracked the impact of COVID-19-induced school closures found moderate to high learning loss depending on socio-economic background and settings.

Rapid learning assessment in the classrooms and at regional levels can help measure the extent and dimensions of COVID-induced learning loss. Remedial and reorientation programmes are more effective when designed with a good understanding of learning gaps. COVID-19 has shown us how important it is to have a learning assessment system; tools such as learning trajectories and surveys of enacted curriculum that equip teachers to transform learning assessments into practical classroom activities will also be crucial.

The education system in Nigeria, like most developing countries, tends towards an age-grade system centred on class or curriculum completion rather than knowledge acquisition. This creates a misalignment between curriculum and actual competencies, leading to higher schooling but lower learning. Reforms such as “Teaching at the Right Level” (TARL) that have been widely implemented in countries such as India and Kenya have sought to address these issues with a new system and slower curriculum centred on learning. While it is still emerging in Nigeria, the adoption rate and its impact on the education system have been low.

School disruption induced by COVID-19 is an opportunity to step-up learning recovery and ensure the curriculum aligns with classroom practices and assessments. The education system should focus more on foundational skills development, ensuring that children acquire the basic numeracy and literacy skills that are building blocks for a life of learning. In addition, the post-COVID-19 education system needs to be better prepared for shocks and technologically driven.

The education workforce was affected by low morale and income shocks induced by COVID-19. Education sector recovery should include targeted social protection for the education workforce and parents. For parents, this includes maintaining the school feeding programme, providing subsidies for school materials such as uniforms and textbooks, and providing income shields for low-income households by expanding access to credit markets. For the education workforce, it is crucial to provide retraining that equips them to transition and adapt to the hybrid learning environment that COVID-19 has spurred. Cross-exchange of ideas on local innovations to recover learning loss will also be important. Globally, countries have been experimenting with ways to recover from the effects of the pandemic, and the education workforce in Nigeria needs to be exposed to what works, where and why. This can create the knowledge base for replication and scaling of innovation.

Nigeria’s education system is variegated, and what works in one state or region may not work in others. For example, evidence suggests that while there are still substantial gender inequalities in access to education in Nigeria’s Northern states, many Southern states have achieved gender parity in this area. Investing in, evaluating through, and learning from grassroots initiatives is important to understand context-specific challenges.

In a nation estimated to be losing 7 to 13 % of its GDP to low human capital development, we cannot overemphasise the role of education as a basis for achieving other Sustainable Development Goals. Focusing on these five dimensions will ensure that the approaches to building back better yield an outcomes driven, learning-focused and equitable education system in Nigeria.

This article was originally published by the OECD Development Matter blog and is part of an article cooperation with Southern Voice.

Amina and Yakubu grew up in the northern part of Nigeria in the 1970s. In early childhood, they experienced one of the worst droughts. They lost the quality of their infancy experience to poor nutrition due to the persistent drought in their childhood locations.

Amina, now unemployed, was conceived during the drought and lived it as a baby. This famine hurt her parent’s income and her mother’s nutrition. Yakubu, with limited labour market opportunities, recounts that the climate crisis made it difficult for his family in the rural area to foster their seasonal crops and rear their herds and livestock. Many members of his community lost thousands of herds due to this drought. Amina and Yakubu are fictitious characters. Yet, they represent the stories of thousands of persons born in the early seventies in northern Nigeria and who experienced the drought’s consequences.

How could one imagine that varying environmental conditions in early life could affect adulthood’s labour market outcomes? In developing countries, this is not far-fetched. The impact of climate shocks can be long-lasting for vulnerable, exposed groups. It is especially true in countries where the effects of climate change are severe, and the resources needed to cope with its consequences are scarce.

The 1972 – 1974 drought that affected the areas in Nigeria where Amina and Yakubu lived provides an appropriate case study. It is argued that it may have affected later labour market outcomes of those exposed to the shocks at the early stages of their life’s formation. How?

The 1972-1974 drought is labelled the worst in recent Nigerian history. Affected areas saw a 60% reduction in farm production, 400,000 cattle deaths, a 13% decline in livestock population, and a 400% increase in food prices. The death of millions of animals and crop failures of between 80 and 100 % in certain affected areas had severe repercussions for women. They depended primarily on farm output for trade and subsistence.

Children born in periods coinciding with the droughts suffer the most severe effects from the climate shock’s economic and nutritional damage. The pre-and early post-natal age group is sensitive. Thus, current circumstances that affect stress levels and nutrition modify their condition for quality development. These circumstances have a lasting impact on the quality of later life. Other infants born in the period immediately before and after the drought are not left out, as the group still coincides with the formative stages of life. Since the group’s formative years coincided with the drought, its implications on household income and health indirectly impacted their healthy development.

Households who depend on agricultural products face a more significant impact, especially those in states more vulnerable to drought. In addition, rising food costs also impact non-agricultural households, affecting their food consumption (not to mention the direct health consequences of the famine). Such shocks to household finances, food intake, and health collectively account for infant stress. It hurts the Intelligence Quotient (IQ), later educational performance and attainment, health, and overall mental health. Such effects on human capital development are expected to impact the adult labour market, with “social consequences”, such as earlier marriage entry.

In contrast to Yakubu, Amina’s labour market risk may have been caused by her childhood household response during the drought. In other words, boys’ schooling takes precedence over girls in times of household economic hardship. Such gender-based reactions to shock incidence in families’ investments in their children’s education are usual in this part of the world. Despite their early life shock exposure in common, such differences in households’ resource allocation between boys and girls may affect outcomes in the long run. It could also be because of the pervasive barriers women face in entering the labour force compared to their male counterparts.

The drought altered Amina and Yakubu’s early life, but Amina was also affected in adulthood. It tells us that a gender-focused policy approach is needed to address the differences in outcomes despite common life experiences. Policymakers and other public sector actors should be gender-intentional in policy designs to lessen adverse climate change impacts on the most vulnerable. A fundamental policy, for instance, could focus on attending to the nutritional deficiencies of pregnant women faced with climate shocks. Policies can also focus on mitigating the consequences of school interruption or human capital deficiencies that may have occurred due to climate change shocks, especially for the most vulnerable.

For people like Amina and Yakubu, these interventions might come too late. But in the light of rising climate change threats and increasing droughts, it is essential to mitigate the long-term effects for future generations around the globe.

This article was Co-authored by Great O. Nnaamani

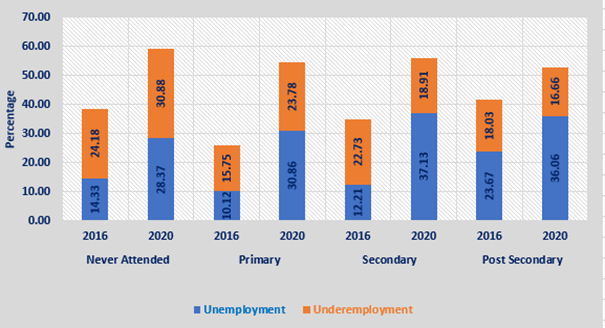

In 2020, Nigeria’s population was estimated to be above 200 million and about 61 percent (122 million) of the population were within the working age. Out of the 122 million in the working age group, 69.7 million are in the labour force and a significant proportion of them are without a job. The most recent unemployment statistics (2020Q4) shows that 33.3 percent of the labour force are unemployed and another 22.8 percent are underemployed. The situation is, however, worse for the young population (those between the ages of 15 and 34 years) as 42.5 percent are unemployed and another 21 percent are underemployed. Similarly, the unemployment situation is higher among those without education as well as those with minimal education as the unemployment rate among those that have not attended school and those with primary school education is 31 percent and 24 percent respectively, relative to 17 percent for those with post-secondary education (see Figure 1). With Nigeria’s population estimated to reach 250 million people by 2030, the unemployment situation is increasingly drawing the attention of relevant stakeholders as the country’s ability to create sufficient jobs for new entrants as well as those in the labour market is undermined.

Figure 1: Unemployment in Nigeria by Level of Education

Source: Authors’ computation from National Bureau of Statistics

IWOSS: the potential solution

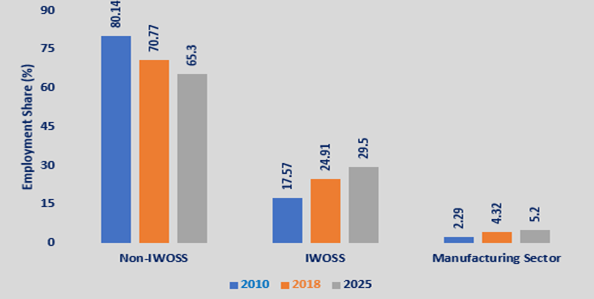

The sluggish growth of Nigeria's manufacturing sector, which otherwise would have absorbed labour, has limited employment creation in the country, as it has in many other African nations. Recent studies highlight alternative industries, referred to as "industries without smokestacks'' (IWOSS), that have many similarities to manufacturing including their tradability, propensity to absorb significant numbers of low-skilled labour, potential to significantly contribute to output, and high productivity. Industries without smokestacks include tourism, horticulture, business services, trade, transportation and logistics, and some information and communication technology (ICT)-based services. In Nigeria, the IWOSS sector is quickly gaining prominence and contributing increasingly to employment from 17.6 percent to 24.9 percent of total employment between 2010 and 2018 (see Figure 2). Hence, the development of the IWOSS sector has the potential to generate an appreciable number of employment opportunities for Nigerians, especially the youths.

Figure 2: Employment in Nigeria: IWOSS and Non-IWOSS

Source: Authors’ calculation based on GDP estimates from the National Bureau of Statistics

IWOSS sectors: employment creation channels

Despite the role of IWOSS sectors in delivering jobs for the population, employment creation in the IWOSS sector is premised on three factors. First, the transition towards climate friendly activities will create new jobs. Also, technological advancement is resulting in new forms of jobs that were not in existence two decades ago and traditional jobs are eroding. Finally, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is expected to increase the growth of new industries in African countries including Nigeria as well as increase demand for the services of existing ones.

Industries without smokestacks (IWOSS) by definition are low CO2 emitting industries. In CoP26, there was a renewed commitment by countries including Nigeria to net zero carbon emissions by 2063. In line with this pledge, Nigeria’s National Development Plan included the green economy as part of the five trends that would shape the world in the next decade. As a result, the Plan provided strategic support for the expansion and emergence of environmentally friendly industries. For instance, the Plan projected the increased use of smart techniques in agriculture. Simply put, commitment towards net zero carbon emissions would lead to the winding down of existing jobs and emergence of new jobs particularly jobs in industries that support the green economy. On this basis, government and business leaders are already making concerted efforts to create new industries that are environmentally friendly.

Moreover, structural change is taking place globally and these changes reflect the impact of technological progress and a changing global marketplace prospect of industrialization. The World Economic Forum identified five high in-demand roles, which are (i) IT and data, (ii) sales and marketing, (iii) operating and logistics, (iv) manufacturing and production and (v) customer facing and front office. Four out of the five identified job roles are related to IWOSS thus, indicating that the job of the future would be found in IWOSS. These opportunities IWOSS offers could be tapped into and accelerated if the Nigerian government amends policies to pave the way for greater investments into the IWOSS sector.

Nigeria has long sought to increase its industrial capacity as a way of harnessing the benefits presented by the AfCFTA, generating employment opportunities, and stimulating GDP growth. The IWOSS sector presents exciting earnings that are geared towards expanding Nigeria’s industrial capacity. The AfCFTA, which was launched on January 1, 2021, integrates 54 of the 55 African Union members, creating a market with a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion. It aims to create a single market for goods, services, and the free movement of labour, and it intends to abolish tariffs on 90 percent of the goods produced in the region. The implementation of the agreement is expected to enhance cross-border financial transactions, expansion of the agro-processing businesses, and increase the demand for transportation and logistics services. Significant number of jobs are expected to be created in these industries with implementation of supportive policies in line with the AfCFTA.

Imperative for Nigeria: the four C’s

To leverage the employment potential of the IWOSS sectors in addressing Nigeria’s employment challenges, these sectors require support from the government. Four ways have been identified through which IWOSS sectors can be supported.

Competitive educational system

In Nigeria, the educational system is underperforming and less competitive. As a result, the students are poorly prepared for the in-demand skills. Except for a few educational institutions, the curriculum which serves as a manual that guides teaching are rarely updated. This phenomenon occurs at every level of education and in part explains the existing skills mismatch between the skills demanded by employers and the skills profile possessed by students graduating from educational institutions. The magnitude of the problem is high due to limited collaboration and coordination between educational and training institutions as well as various industries.

The government needs to provide a framework that strengthens the flourishing of a competitive education system. This is important in ensuring that students are taught in-demand skills. In other words, the educational system prepares the students with skills necessary for them to be competitive in the job markets. Also, the learning structure includes internship positions to intimate the students with industry demands.

Commitment to improvement in infrastructure

Nigeria’s infrastructural deficit is enormous and constitute a drag to economic growth and development. Recent evidence suggests that Nigeria still lags and needs to intensify efforts to improve its digital economy. In Nigeria, digitization opportunities are limited in a variety of ways. Some are the result of deficiencies in digital infrastructure and digital skills, while others relate to how the digital economy is controlled. In other words, the existing deficiency in digital infrastructure has constrained the competitiveness of Nigeria's e-commerce and logistics business, thereby lowering the extent to which they can expand, and suggesting that there are ample rooms for growth. In addition, the power and transportation are grossly inadequate and affects the efficiency of firms. Commitment to improve infrastructure should therefore include the power and the transportation infrastructure. The power sector infrastructure should aim at simultaneously expanding the country’s power generating capacity and transmission. Similarly, the investment in transportation is crucial in reducing congestion at port and commuting time, which indirectly increases the cost of doing business in the country. These interventions can transcend to positive IWOSS sector productivity. Governments, policymakers, and key stakeholders should collaborate to increase investment in infrastructure.

Coordination of climate actions

The Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals emphasised environmental sustainability when describing economic growth. As a result, the direction has shifted from economic growth to sustainable growth or a green economy. While the green economy was incorporated in the National Development Plan, the government needs to create a structure that will ensure that the private sector acts in a coordinated way. In other words, the activities of the private sector targeted at achieving net zero carbon emissions needs to be coordinated to prevent repetitive activities and optimise actions towards achieving the goal. For instance, the government has to work more closely with the private sector and research institutions in creating knowledge aggregating platform and events to ease the dissemination of climate related information. These platform and events would create opportunity for different actors working on climate change adaption and mitigation strategies to have up-to-date information on new development, especially those within the country.

Creation of innovative financing options for MSMEs

Small businesses are the engine of economic growth and are very crucial in fostering job creation in the IWOSS sector. Recent evidence suggests that, in 2020, Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) constitute about 96.9 percent of total number of businesses and contributes about 46.3 percent of the total GDP. However, their growth has been hindered by lack of access to finance with significant share of small business owners relying on their personal savings and borrowing from friends and family to support business operation. Small businesses account for less than 5 percent of commercial bank credit, which contributes in part to their financing gap estimated at about N617.3 billion annually. While there are existing funding schemes targeted to MSMEs, their scale of operation is very limited. Addressing financing gaps among the MSMEs is crucial in optimising their contribution to job creation, otherwise, firms with potential remain small or die within few years of establishment. The Development Bank of Nigeria, Central Bank of Nigeria, and Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency of Nigeria need to partner with financial institutions to design additional innovative financing schemes (and expanding already existing ones) that would provide MSMEs with finance at scale and at affordable rate. The financing scheme should be designed in a form of cooperative structure such that the beneficiary of the funds is accountable to other cooperative members.

Conclusion

In the National Development Plan, 2021 - 2025, the Nigerian government aims to create 21 million jobs by the end of 2025 through the private sector. This article makes a case about the capacity of the IWOSS sectors in driving employment creation in Nigeria, and the need to prioritise it. While the evidence about the IWOSS sector in Nigeria is scarce, this piece highlights the potential of the sector in addressing the employment crisis in Nigeria. As a result, the article notes four imperatives to upscale the impact of the IWOSS sector. They are (i) competitive educational systems, (ii) commitment to improvement in infrastructure, (iii) coordination of climate change actions, and (iv) creation of innovative financing options for SMEs. These actions would go a long way toward enabling the IWOSS sectors to catalyse employment creation.