Comparative Study of Policy Responses to COVID-19 in LICs in Africa

This brief assesses the policy responses to COVID-19 among low-income countries (LICs) in Africa.

Recommendations:

- Address the structural bottlenecks impeding the effective implementation of an appropriate policy mix by African LICs. A key focus area is ensuring the independence of monetary and debt management authorities with a view to achieving fiscal sustainability and controlling inflation.

- Implement a data-driven approach to policy formulation in the context of COVID-19 economic management, as this will streamline recovery efforts and enhance results.

- Maintain official development assistance as an intervention during the COVID-19 economic recovery phase as it is crucial for those LICs (particularly fragile states) with limited capacity to mobilise their own domestic resources.

- Address structural weaknesses in key sectors, many of which have been exposed by COVID-19. Priority should be given to broadening the digital economy as well as financial and social inclusion, which will have significant, long-term benefits.

Executive summary

This brief assesses the policy responses to COVID-19 among low-income countries (LICs) in Africa. While LICs have adopted expansionary fiscal and monetary policies in the face of economic lockdown, as well as other mitigation strategies, the scale and quality of such responses have been modest compared with those of emerging and middle-income countries. Policy instruments have also varied across countries, in line with the level of development of domestic financial markets and the extent of digital inclusion. Pre-pandemic economic challenges, such as limited fiscal space, high debt levels and inflation, have also contributed to countries’ weak economic responses. External financing has been crucial for LICs’ ability to respond to the pandemic, but, is still inadequate given the huge financial gap that exists. As LICs move from the relief to the recovery phase of COVID-19 economic management, a rethinking of economic responses is crucial both to bring about a swift recovery and to minimise the catastrophic impact of COVID-19 on recent developmental gains.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating effect on both developed and developing countries. While the burden of disease and the health implications have been felt most acutely by developed and a few emerging economies, all countries have experienced serious economic consequences. At the peak of the crisis, 161 countries were under some form of lockdown, which put a severe strain on their economic and trade activities. Developed countries used their enormous financial capacity to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic with expansionary fiscal and monetary policies and social palliatives. By April 2020, the US alone had spent over $6 trillion in COVID-19 response measures, while the EU later introduced a $500 billion stimulus package.

Low-income countries (LICs) in Africa, in turn, responded to the health crisis with lockdowns and the heavy curtailment of economic activity. However, the scale and scope of their mitigation strategies paled in comparison with those of most developed countries. The total COVID-19 budget of African countries stood at $37.8 billion in April 2020, with South Africa and Egypt responsible for 84% of that amount. This implies that most LICs lack the financial capacity to respond meaningfully to the pandemic. In addition, prospects of securing external financial assistance are limited, given that every country is facing a similar crisis.

With many countries already reopening their economies and focusing on recovery efforts, important questions need to be asked about the African LIC experience. In the initial phase of the crisis, how did African LICs use the various policy tools at their disposal (fiscal, monetary and exchange rate) to effectively manage the crisis? How did their economic responses evolve – especially compared with their responses to past economic challenges, like the global financial crisis (GFC)? What worked, where did it work and why did it work? Looking ahead, what crucial lessons have LICs learned from economic recovery efforts? This policy brief delves into these important questions.

Economic policy responses to COVID-19 among LICs in Africa

While public health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have followed a similar pattern of public awareness creation, testing, tracking, therapeutic management of those infected and physical restrictions (lockdowns and shutdowns) to curb its spread, economic responses have varied significantly across countries, given different fiscal space and prepandemic economic fundamentals.

Economic responses have cut across three policy domains: fiscal; monetary and macro-financial; and exchange rate/ balance of payments. Economic responses have also been shifting as the pandemic has progressed. At the onset, the focus of economic policy responses was on delivering relief to vulnerable populations and those in precarious employment whose livelihoods were affected by the lockdowns. Now, with a better understanding of the patterns and effects of the disease, more countries in Africa are moving towards reopening their economies and directing their economic policy responses at recovery, following the initial economic shocks.

Below we briefly enumerate these policy responses among LICs in Africa and compare how these interventions diverge from past responses to economic crises, notably the 2007– 2008 GFC.

Fiscal policy: This includes economy-wide and sectoral interventions using taxation/subsidy, public expenditure and deficit-financing instruments. The first line of intervention in many countries is emergency budget support for the health sector and the scaling up of social protection for vulnerable households in the form of direct cash transfers, a debt moratorium, and financial support for small and mediumsized enterprises and the informal sector. In many cases, expenditure has been reprioritised to focus on immediate needs in the health sector. For countries with less fiscal space, interventions have taken the form of taxation-related measures, such as tax relief and utility bill freezes, among others. There has also been an increase in deficit financing or drawing down savings.

Most LICs in Africa have used one or more forms of the fiscal policy instruments mentioned above. The most common fiscal policy instrument has been budget support for the health sector, through either reprioritisation or an expansionary policy. Only a few LICs have implemented social transfer programmes/support for households or firms. Moreover, the size of countries’ fiscal stimulus has been small, generally ranging from 1% to 2% of gross domestic product (GDP).1The few exceptions among LICs are Senegal, Niger, Mozambique and Namibia, whose fiscal stimulus injections have amounted to more than 4% of GDP. Other limiting factors in terms of fiscal response (which were evident before the pandemic) are the absence of a social register, especially for urban residents who have carried practically the full burden of the lockdown, and low financial and digital inclusion, which has constrained the distribution of support. Despite these constraints, LICs have still managed to introduce several innovative and cost-effective interventions, such as tax relief (Senegal and Madagascar), a utility bill freeze and a waiver of fees for basic services (Niger), and the distribution of food aid (Senegal and Liberia).2

On the revenue side, the pandemic has affected the economic performance of most African countries, with government revenue projected to decline by more than 12% in 2020. Domestic resources thus make a limited contribution to government policy responses. However, early debt forgiveness and credit facilities granted by donors have helped to expand fiscal space in many LICs on the continent.

Monetary and macro-financial policy: Central banks, in a coordinated effort with fiscal authorities, have used expansionary monetary policy, in the form of increased money supply, through traditional, open-market operations as well as quantitative easing. Another tool that central banks are deploying is macro-financial assistance, which comprises medium/long-term loans or grants to businesses or households, as a way of cutting through the commercial banking system. In addition, there are support measures for commercial banks and other financial intermediaries that take the form of extended credit lines, higher liquidity and extensions to collateral frameworks. However, monetary policy interventions face some risks when it comes to managing the trade-off between growth-enhancing policies and inflation. Central banks are also using moral suasion and forward guidance to encourage commitment to specific policy directions in a bid to stabilise the financial system.

Expansionary monetary policy is by far the most common economic response deployed by African LICs.3One reason for its popularity is that the fiscal space in most countries is heavily constrained owing to high debt levels and weak revenue flows. A change in interest rate policy is another widely used instrument. Countries in the Economic Community of Central African States, which have limited control over interest rate policy, mostly rely on injections of liquidity and extended deadlines for the repayment of loan securities held by credit institutions. Nine of the LICs in Africa implement no monetary policies, according to the World Bank.4These are mostly countries whose weak financial markets make the application of monetary policy difficult. In many countries, too, the use and likely effectiveness of monetary policy is influenced by high inflation, which was evident before the pandemic.

Exchange rate/balance of payments policy: The COVID-19 pandemic has affected demand patterns and global supply chains to the extent that they have disrupted foreign exchange earnings for many African LICs. The oil price crash that occurred during the pandemic generated an additional external shock for petro states and worsened foreign reserves. Some countries, like Nigeria, responded to this threat by changing the exchange rate regime or depreciating their currency.5In addition, countries that lost control of inflation owing to their expansionary monetary policies used exchange rate policy as an alternative tool to address inflationary pressures.

Among the LICs in Africa, only Zimbabwe has made an explicit change to its exchange rate policy, by moving from a flexible to a fixed exchange rate in the face of the country’s forex crisis. However, most countries’ monetary authorities are using forward guidance to win support for interventions in forex markets in cases of high volatility or significant currency depreciation. For example, the banks of Uganda, Comoros and Sierra Leone have committed to intervening in the foreign exchange market.6In contrast, Angola, Eswatini and Nigeria (all lower-middle-income countries) have depreciated their currencies in response to COVID-induced economic shocks.

LICs have recorded fewer cases of currency depreciation than the frontier economies in Africa. Overall, the exchange rate policy has not played a major role in LICs’ policy responses in recent months.

Donor support for African LICs in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic

Given the inadequate scale of domestic resources among LICs, the second layer of interventions has come in the form of donor support. This includes multilateral support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the African Development Bank (AfDB), as well as bilateral interventions from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries and even countries in the Global South. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA)7has collected detailed data on appeals for funding from developing countries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the total receipts so far.

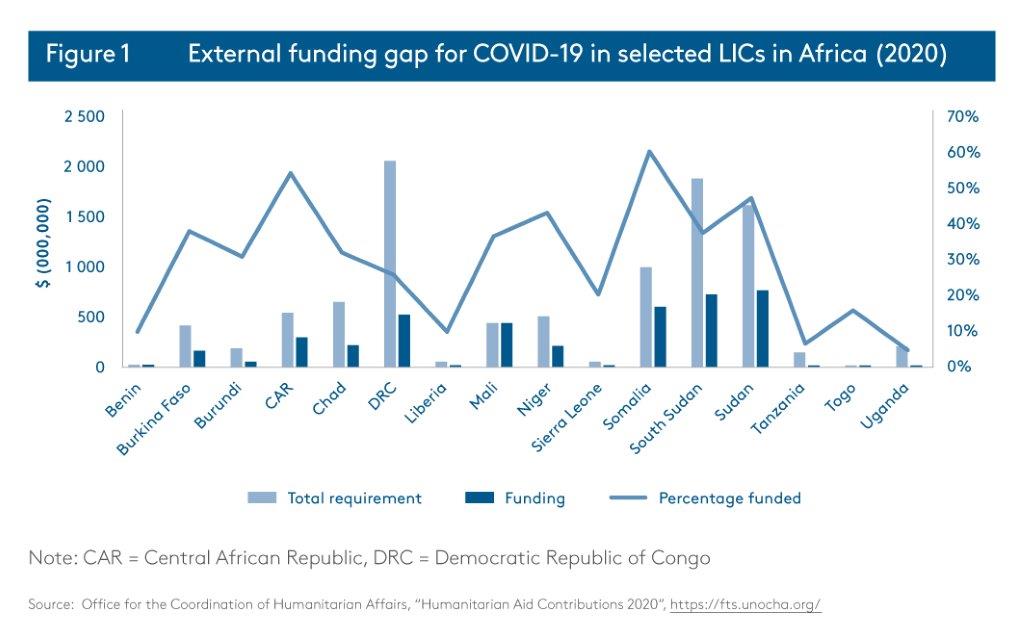

As shown in Figure 1, a financing gap (the difference between need and actual allocation) is observed for all LICs, but it varies across countries. For example, Somalia and the Central African Republic have received 60% and 54%, respectively, of their appeal funds, while Uganda and Tanzania have received only 5% and 7%, respectively. A notable trend is that fragile states receive a higher proportion of the funds for which they have appealed, which is an indication of the priority given to disadvantaged countries in terms of donor interventions.

Debt relief and a moratorium on debt services are other forms of external support. The World Bank, the IMF, the G20, the AfDB and all Paris Club creditors granted debt relief to 18 LICs in Africa as part of the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust. The IMF also activated emergency lending facilities for African countries. China, in turn, introduced a series of debt relief and debt service suspension measures for African countries. However, with African countries having incurred more than $350 billion in debt, the debt forgiveness and relief measures represent modest support given LICs’ enormous financial needs. There are also concerns that creditors could in the future penalise those African countries requesting debt relief. Mutize notes that most African countries eligible for a debt moratorium have so far refused to apply because of the risk of credit rating downgrades.8

There are also private philanthropic support measures. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has committed $1.6 billion over five years to ensure that the most vulnerable in the world can access a COVID-19 vaccine once developed. However, most philanthropic and bilateral support is aimed at health interventions, while economic support in many cases relies on the intervention of multilateral institutions. An analysis of trends in foreign aid and donor support shows that, in line with UNOCHA data, LICs in Africa have accessed some donor support, although this has been insufficient relative to their financial needs.

Effectiveness of African LICs’ economic responses

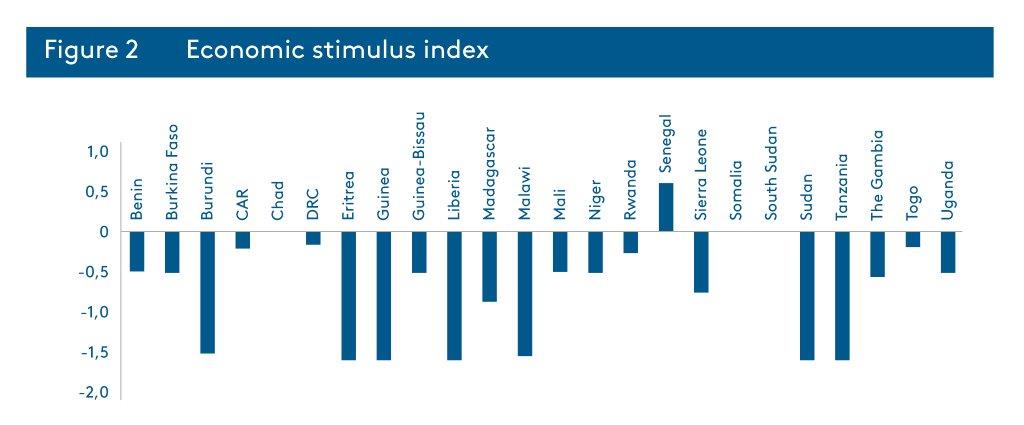

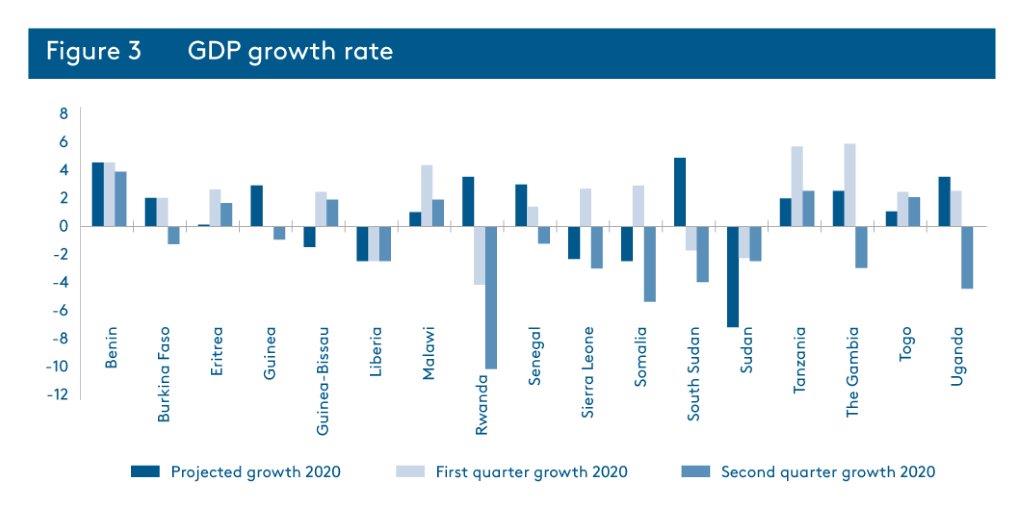

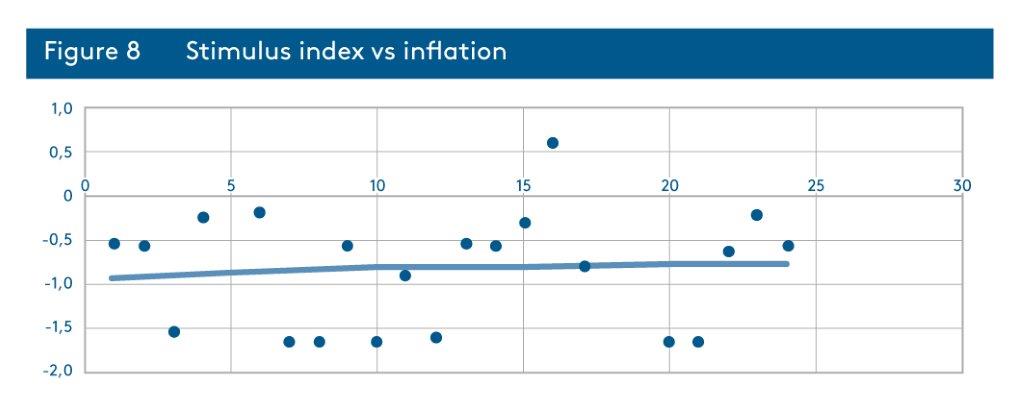

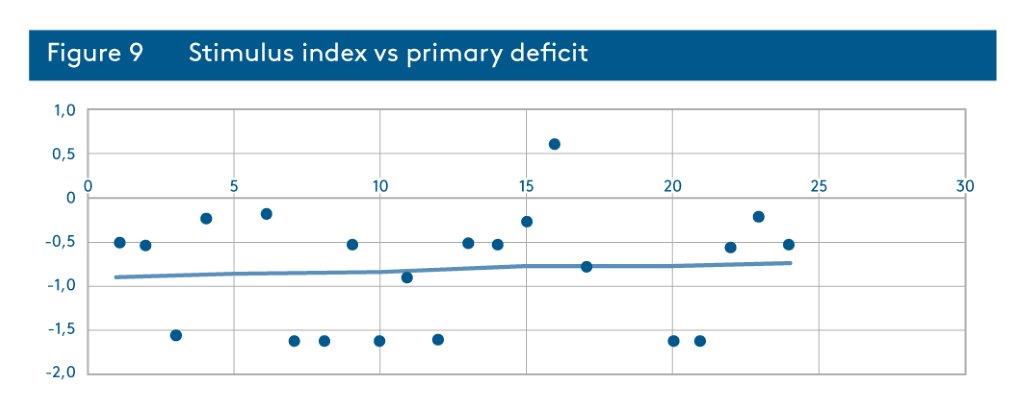

Given that the COVID-19 pandemic is still prevalent throughout the world, it is difficult to accurately gauge the effectiveness of various policy responses to date. Nevertheless, the policy interest that COVID-19 has stirred has prompted the capturing of much data using many indicators that have been useful in periodically tracking the virus’s economic and epidemiological effects. Elgin, Basbug and Yalaman9developed an economic stimulus index to track monetary, fiscal and exchange rate policy responses across countries. We used this index to assess the performance of LICs in Africa in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. We also compared the IMF’s projected growth rates among LICs, which are measures of the likely impact of COVID-19, to the actual growth rates in the first and second quarters of 2020.

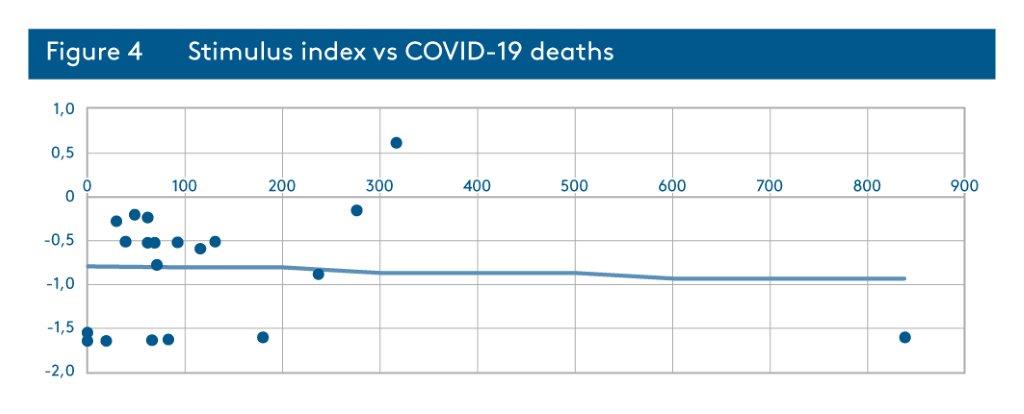

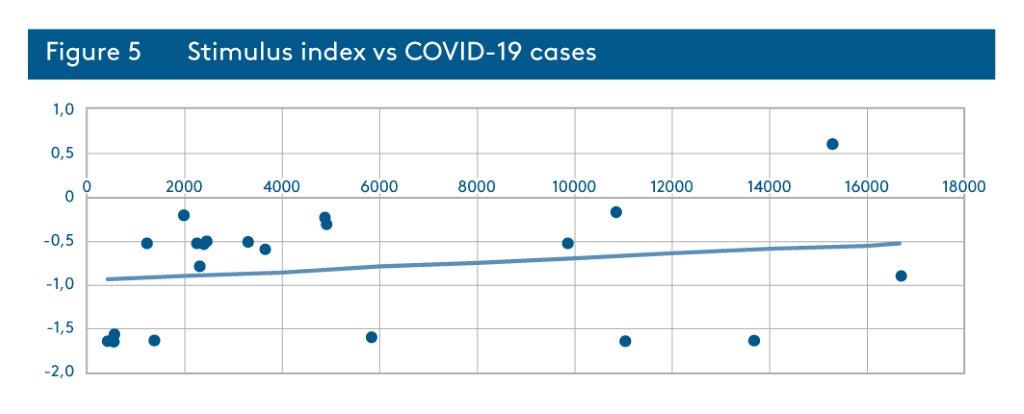

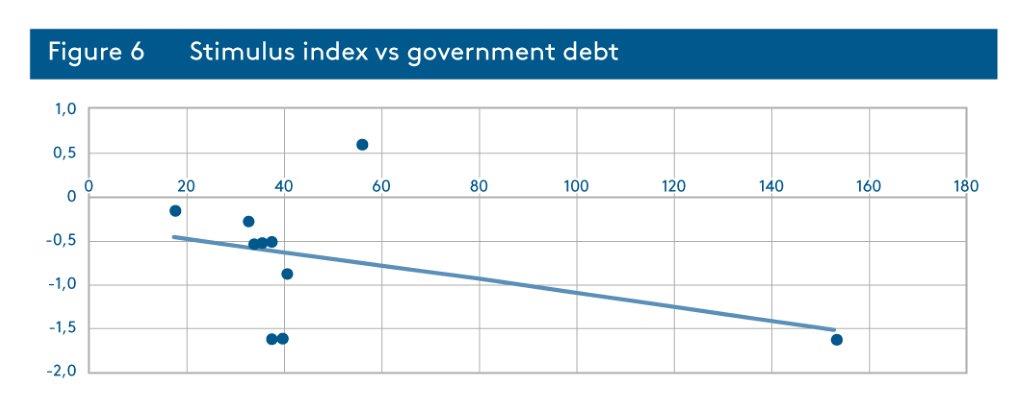

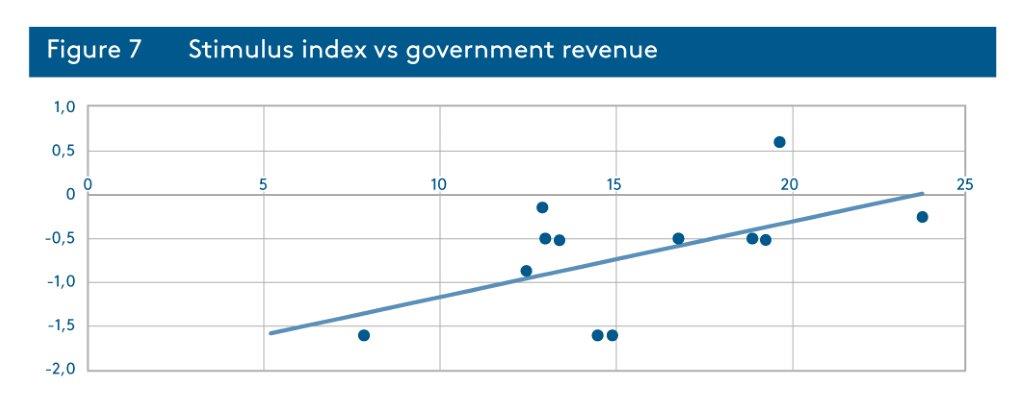

Furthermore, we correlated the stimulus index with key economic indicators prior to COVID-19 to assess the factors driving the observed country-by-country differences in policy design. The variables examined included: debt level, inflation and revenue over five years (2015–19) prior to the pandemic. High debt levels might constrain effective policy responses because of limited fiscal space. A similar argument holds for revenue; as better income streams are key to being able to pursue a countercyclical policy. In addition, inflation reduces the extent to which the monetary authority can push for an expansionary policy. Lastly, we compared the stimulus index to the incidence of and deaths from COVID-19. The results are reported in the Appendix.

The analysis showed that the economic response has been weak across African LICs, with all countries (except Senegal) recording a negative score. Similarly, comparing the actual and projected growth rates revealed that many LICs’ growth rates have been worse than projected – especially in the second quarter of 2020, which coincided with the peak of the COVID-19-induced lockdowns. We found the stimulus index to be positively correlated with the number of COVID-19 cases, while the number of deaths showed a negative but nevertheless weak relationship. This suggests that countries’ response levels are driven by the incidence of the virus and not the death rate.

Countries with high debt levels before the crisis had lower scores on the stimulus index, while those with high revenue levels had higher scores. This aligns with the argument that limited fiscal space constraints LICs’ macroeconomic responsiveness. In the same vein, the stimulus index is lower among countries with high inflation before the pandemic, again illustrating that a weak macroeconomic environment is a major constraint to effective policy responses to COVID-19. Overall, the weak economic response among LICs in Africa is a manifestation of past economic problems. This finding is supported by the literature on the importance of initial conditions for economic development.10

Comparison of COVID-19 and GFC economic policy responses

The COVID-19 crisis bears some resemblance to the GFC. For LICs, both came in the form of an external shock emanating from developed countries and transmitted through trade and the economic interdependency among nations. The transmission mechanisms were also similar, with a decline in global trade, remittances, foreign aid and commodity prices dominating. However, the magnitude of COVID-19 and the speed with which it has unfolded have been much greater than those of the GFC. In just three months, COVID-19 managed to turn around the 2020 global economic outlook (output) from more than 3% to -3%.

With both the GFC and COVID-19, the majority of LICs in Africa pursued expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to absorb the economic shock. However, they had more space to use fiscal policy at the time of the GFC, as the crisis came after the implementation of the LIC debt forgiveness programmes. Furthermore, non-resource-dependent countries were only marginally affected by the GFC, with some even benefiting from lower fuel and food prices.11In fact, economic growth declined only slightly among African LICs during the crisis.

During the GFC, LICs responded to changes with macroprudential policies to strengthen the financial system. The response to COVID-19 has in turn centred on strengthening the health system and developing social security facilities for vulnerable groups. The donor support measures during the two crises were similar. In terms of development assistance, priority was given to fragile and post-conflict states. Multilateral institutions also introduced special facilities that African countries could tap, with the IMF, World Bank and AfDB providing facilities to improve trade, the financial system, foreign reserves and infrastructure. In addition, the IMF created Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to the value of $250 billion, which countries can access up to their IMF quota share. This has proved useful for LICs during the COVID-19 crisis. However, policy tools like debt forgiveness were of limited use during the GFC compared to their value during COVID-19. Overall, there were inadequate funds for African LICs to effectively respond to the two crises.

In terms of differences in economic policy responses, social palliatives were used in very few African countries during the GFC. Bilateral support was much more prevalent – although complementary to the multilateral support – during the GFC. In contrast, donor support for COVID-19 has largely come from multilateral institutions. In addition, COVID-19 has been greeted by a better-capacitated financial system (ie, capital reserves), whereas the financial sector was found wanting during the 2007–2008 GFC. Lastly, in African countries’ responses to the GFC, regional cooperation had a stronger role to play, especially in the area of monetary policy. African governments set up the Committee of Central and Regional Bank Governors (C-10) at the beginning of the GFC. During COVID-19, while there have been areas of coordination in health policy (eg, the Africa Taskforce for Novel Coronavirus) and fiscal policy (eg, the creation of a Continental Solidarity Anti-COVID-19 Fund), monetary policy has been less coordinated among African countries.

However, the economic impact of COVID-19 on LICs is expected to be greater owing to the slowdown in trade and economic activity, and unequal access to COVID-19 therapeutic treatments. In addition, while poverty levels did not rise in the face of the GFC, most research findings point to a sharp increase in poverty rates (for the first time in three decades) owing to COVID-19.12

Emerging issues and lessons for economic recovery

A gradual reopening of the economy has been evident in all LICs. At the time of writing, the policy focus was centred on recovery efforts. In this phase, fiscal and monetary policies will remain not only relevant but also crucial. However, several pertinent issues and lessons from the relief phase should guide recovery efforts and policy responses.

Inability to harness multiple policy instruments: Unlike high-income and middle-income countries that simultaneously deployed fiscal and monetary policies in response to COVID-19, most African LICs have been able to effectively use only one instrument. High debt levels and inflation, as well as other structural issues, have limited policy options. In the long run, the structural bottlenecks impeding the effective implementation of economic policies by LICs need to be addressed using a more nuanced approach. This will require reforming economic institutions and processes to drive inclusive growth. An important focus area is the independence of monetary and debt management authorities, which is crucial for fiscal sustainability and controlling inflation.

Importance of a switch to a data-driven approach: The initial response to the pandemic in most African countries was simply to copy the template from developed countries.13For example, lockdowns and economic shutdowns were reversed in many countries after recognition of the limited capacity of governments to provide palliatives. This led to a more data-driven approach, which is consistent with countries’ economic structure and disease prevalence. Similarly, recovery efforts should be anchored on the same data-driven approach, with the interests of vulnerable populations prioritised.

Need for better leveraging of international cooperation: Official development assistance plays a prominent role in African LICs’ economic responses. It will continue to be crucial for COVID-19 recovery efforts, especially in the case of fragile states that have limited capacity to mobilise domestic resources and are heavily reliant on external support and trade. Nevertheless, it is important to look inwards to the Global South and other countries in Africa. Intra-Africa trade is one area that LICs can leverage for stronger resource mobilisation and growth. For example, the opportunities created by the African Continental Free Trade Area, which is expected to commence on 1 January 2021, can be tapped by LICs.

Rethinking of economic structure: Some of the structural hurdles facing LICs in Africa, which COVID-19 has exposed, include weaknesses in the digital economy, a lack of financial and social inclusion, and poorly developed domestic financial markets. Also, contrary to conventional economic thinking, many LICs follow pro-cyclical policies – ie, not saving during an economic boom – which a countries’ preparedness and ability to respond effectively to a sudden economic crisis. A long-term process to address these failures needs to be set in motion as part of countries’ broad recovery plans.

Conclusion

This analysis has revealed that economic policy responses among LICs in Africa have been suboptimal in the face of existing, pre-pandemic economic challenges. These challenges, which have simply been amplified by the crisis, include poor fiscal positions, deficiencies in human capital development, and a general absence of crucial hard and soft infrastructure. It is therefore important that recovery efforts are used as a springboard for long-term development across the continent. Indeed, a holistic and comprehensive intervention in these areas should be front and centre of the conversation on economic recovery going forward.

Appendix

This article was first published at Compra

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China