Company and Allied Matters Act (CAMA) 2020: Enhancing a better business environment for MSMEs in Nigeria Under AfCFTA

With the passing into law of the reformed Company and Allied Matters Act (CAMA, 2020) which replaces the CAMA 1990 Act, Nigeria is uniquely positioned to be in the top 20 of doing business rating globally by 2030. At this time when the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), one of the world largest Continental Trade Area (CTA)- with 54 African member nations signed, the reformed CAMA Act could be a big boost to the Ease-of-Doing-Business (EoDB) for Nigerian Micro-Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) to flourish under a competitive environment. This piece highlights some of the critical changes which the new CAMA Act introduces to the principal framework regulating the business climate in Nigeria and how it could promote MSMEs to be competitive under the AfCFTA.

Background of Companies and Allied Matters Act in Nigeria

Companies and Allied Matters Act (CAMA) is one of the critical pieces of legislation which enhances better business climate and promotes Micro, Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (MSMEs). The Act provides a regulatory framework for how businesses should be carried out in the country.The CAMA 1990 Act, which repeal CAMA act of 1968 reshaped the business environment of Nigeria in the 90’s. CAMA 1990 was passed into law to establish the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC), providing for the incorporation of companies and incidental matters, registration of business names and the incorporation of Trustees of certain Communities, bodies and Associations. The Act was promulgated to repeal the Companies Act of 1968. However, in the last 30 years of promulgation into law, the Nigerian corporate landscape has transformed with global and regional demand for business integration. Hence, the CAMA 1990 Act was heavily hamstrung by several provisions of the Act which limits modern business practices in the light of national and global reforms.

The private sector had clamoured for a reformed CAMA because the economy has changed, there are new parameters in the way of doing business both domestically and internationally. As a result of this, the need for public-private partnership in promoting sustainability in the business climate of the country after several attempts to review the CAMA 1990 was inevitable. Also, technological innovation in the business sector had propelled for collaboration for a new legislation that would align with global business practices. The signing into law of the CAMA 2020 has raised hope for the private sector with the recent regional trade integration (AfCFTA). However, without effective monitoring and implementation, this new reform especially in promoting MSMEs which are drivers of growth in developing nations would never fulfil its purpose.

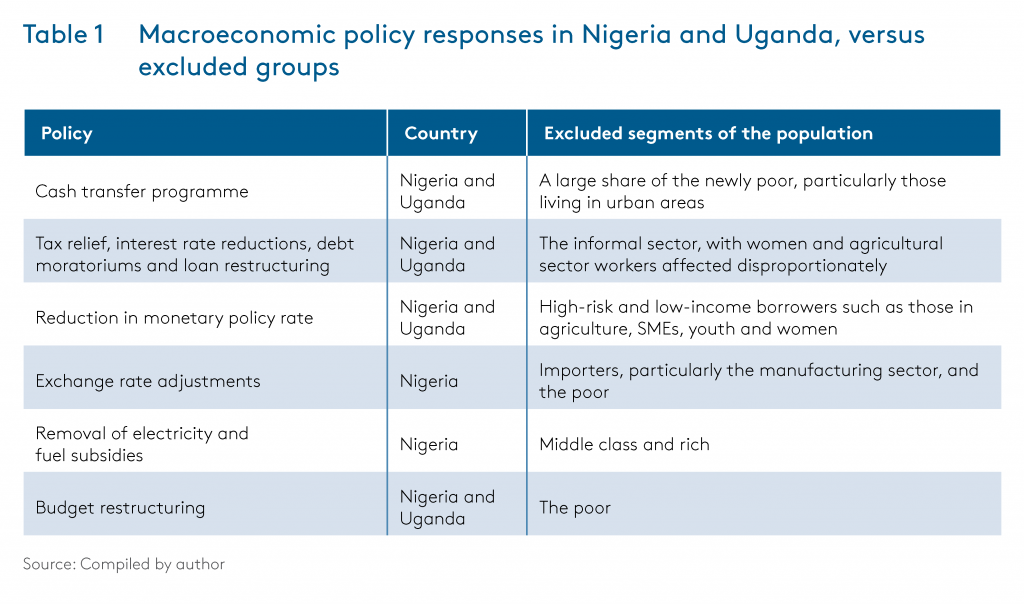

Figure 1.

Source: World Bank Group- Doing Business Reports

Nigeria had never been ranked in the global top 50 economies by the Doing Business report of the World Bank since inception, but the country had a steady EoDB score as shown in Figure 1. Also, Nigeria is reported as one of the 20 improvers of the ease in doing business among others- Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Togo, Bahrain, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Kuwait, China, and India.

The impact of CAMA 2020 Act in the Ease of Doing Business

The objective of the reformed CAMA 2020 Act is to promote legislation for regulatory quality and efficiency which would enable efficient EoDB for Nigerian businesses in general, and MSMEs in particular. MSMEs are the engine of growth for most developing nations. As can be expected, without reforms for enabling business environments to sync with global business evolution, most businesses may shut down due to economic and environmental shocks. It follows logically that without reforms in a rapidly changing global market, most firms-MSMEs especially may not survive beyond the unanticipated COVID-19 pandemic.

Specifically, the reformed CAMA 2020 Act among other things, made the starting and running of business more seamless and less expensive by operationalizing electronic platforms that integrate the tax authority and the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC). Considering that Nigeria is largely dominated by Medium and Small-Scale Enterprises (MSMEs), making business registration or company incorporation easier will bring in more businesses into the formal space. This also will enhance tax revenue for the government. The Act has 870 sections and divided into 7 parts as against 612 sections in the repealed Act of 1990. 167 sections were completely new, while 91 sections were modified.

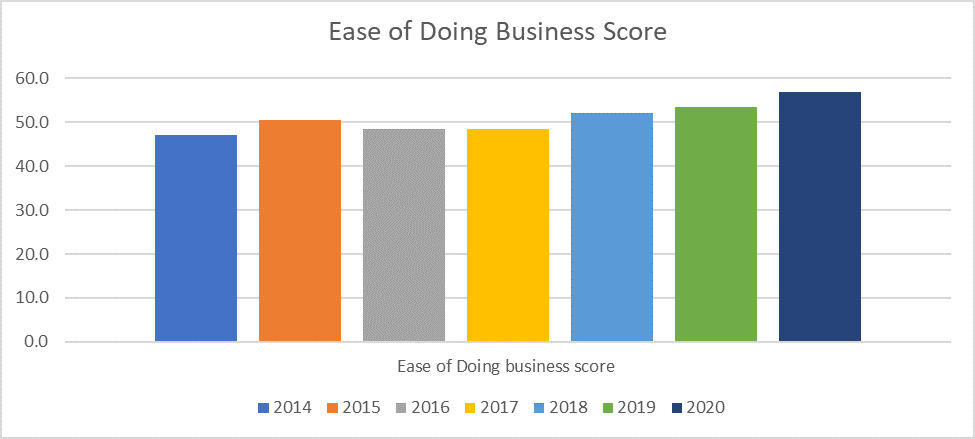

Some of the major alterations made to the Act which directly promote the ease of doing business in Nigeria compared to the repealed Act and its implications on EoDB are highlighted in Table 1 below:

Table 1.

| S/N | ITEM | CAMA 1990 | CAMA 2020 | IMPLICATIONS |

| 1. | Single member shareholding | All registered companies with CAC and under CAMA must either be a private company or public company. | Introduced limited liability partnership and limited partnership. Also, introduces Single member, single share/holding company. | Section 18(2) of the new CAMA 2020 now makes it possible for one member or shareholder to establish a private company which may encourage MSMEs to register their companies and may shrink the informal sector. |

| 2. | Registration of company | To register a company with CAC, the applicant must meet the CAMA 1990 requirements of registration. | Introduction of Electronic filing, electronic share transfer, and E-meetings. | The Act permits electronic filing, share transfers and electronic tax payments.it also allows E-meetings for private limited companies and virtual annual general meetings for public limited companies. |

| 3. | Statement of Compliance | Declaration of Compliance also known as the ‘Attestation of Compliance’ required to be made by a Legal practitioner. | The new Act introduces the Statement of Compliance which does not require attestation by a Legal practitioner. | With the Statement of Compliance, the promoters/owner(s) of the company can take and give an undertaking that all papers of registration requirements have been met and signed off by themselves. |

| 4. | Minimum share Capital | Companies must meet a minimum authorized share capital before incorporation which shall be N10,000 for private companies and N500,000 for public companies | Introduces minimum issued share capital as against authorized share capital. Private companies upon incorporation must have an initial issued share of N100,000 in nominal value from its share capital while for public companies, N2,000,000 in nominal value of its share capital must have been issued. | This implies that what is required now is number of shares but no longer the share capital of the company. |

| 5. | Audit obligations | Every company is mandated to appoint auditor/auditors to audit their financial records/statements in respect of a financial year and presented during the annual general meeting of such company. | Audit obligation is no longer required for MSMEs and companies that had not carried out business since incorporation (excluding Banks and insurance companies) are now exempted from audit obligation. | This will positively impact the profit margins for small companies because audit fee and bureaucratic challenges involved has been removed. |

| 6. | Filing fee and acquisition of Company seal | The company seal is a requirement for incorporation and every company would be charged a filing fee. | Company seal and share certificate, an optional requirement may now be issued as a way of deed duly signed by the company. Also, reduction of fees to 0.35% which is 65% reduction in the entire regime. | The use of company seals has become dormant all over the world. Therefore, it promotes the ease of doing business in Nigeria. |

| 7. | Insolvency regime | Under this Act, the first recourse taken by creditors to recover bad-debts Without exploring other options by which debtors could achieve business recovery in order to repay their debts is insolvency. | Introduction of an extensive insolvency regime. The CAMA 2020 introduces concept of corporate voluntary arrangement which allows a company to settle its debts by paying only a proportion of the amount which it owes to its creditors. | The new CAMA allows companies to explore other alternatives by which to avoid insolvency such as restructuring |

The amendments made in the CAMA 2020 Act may positively impact the EoDB in Nigeria especially at this time when the AfCFTA is implemented. Although, the Act had factored in new methods while embracing technological changes in the business world. It is expected that without practical implementation of the CAMA 2020 by the CAC, the country’s business landscape would not catch up with international business practices. Therefore, it is hoped that the practical administration of the new CAMA will help ease the strain of doing business, and will enhance productivity and promote ease of doing business in Nigeria.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China