Nigeria’s New National Minimum Wage: Responses and Implications for the Economy

By Peace John

On March 19, 2019, the new national minimum wage bill, an issue that featured widely in the 2019 presidential campaigns, finally received legislative approval. The Senate approved ₦30,000 as the new National minimum wage, after nearly 8 years of no-increase from the ₦18,000 paid as minimum wage since 2011. The wage increase was due for review in 2016 according to the law that stipulates that minimum wage should be reviewed at least once every 5 years. As of 2017, Nigeria’s labour and trade unions had initiated agitations and advocacy for a raise for minimum wage workers, particularly owing to the over-due review and inflation’s effect on the value of the wages received. The sustained outcry undertook threatening dimensions, such as strikes and protests on several occasions, to accentuate their demands. Now, their voices have been heard, and what seems to be an applaudable achievement for them, if implemented, may bring with it several short-term and long-term fiscal and economic implications for Nigeria. More importantly, based on prevailing economic realities in Nigeria, it is one thing to approve wage policies and another thing to possess the unwavering capacity to pay the agreed amount. In light of the newly approved minimum wage, this piece highlights the plausible responses of the government, businesses, and the macro-economy at large.

Fiscal Responses

Government’s Non-capital Spending to expand.

As the new wage policy awaits the president’s assent, implementation processes become potentially inevitable and the government is expected to fund the costs arising from implementing the policy. Such costs arise in the form of an increase in personnel expenses with spikes in the percentage of the government revenue utilized for wage bills. According to the CBN, the federal government’s personnel cost rose by 18.5% to N1.85 trillion as the minimum wage was increased from N7,500 to N18,000 in 2011, thus accounting for 52% of FG retained revenue. By 2016, personnel spending had gulped about 59% of FG’s N3.2 trillion revenue and is now projected to enlarge to N2.29 trillion in 2019. With the new minimum wage approved, the government is expected to tender a supplementary budget that would provide for the imminent rise in the wage bill. While the federal government is faced with this stern burden of incorporating the new wage bill into its already strained finances, states face a more severe test given the recurring struggles to pay salaries. These excessive burdens may leave the governments with no choice than to increase borrowing to settle personnel costs – causing a devastating swing on the country’s high debt profile. However, given the shortfall in borrowing capacity, borrowing is almost not an option to be considered. Alternatively, a lower hanging fruit may remain an increase in taxation, particularly Value Added Tax (VAT) – but it has its implications.

Increase in tax rate almost inevitable

Taxation is one means, among many others, used by governments to boost revenue and meet fiscal obligations. To enable the Nigerian government to generate more revenue sufficient to fund the supplementary budget, it is considering an increase in tax rate (VAT). At the prevailing standard 5% VAT, the government generated from about N482 billion in 2013 to N972.3 billion and N1.1 trillion in 2017 and 2018 respectively. However, the tax revenue together with IGR and others, were not sufficient to cater to some states salary structures as many workers were owed salaries for several months. With the recent consideration of 50% rate increase, a VAT would be applied at 7.5% if implemented. The new rate provides a renewed opportunity for the government to garner more revenue; however, the actual point of concern is if this likely increase in revenue will be sufficient to pay the new minimum wage. Although no empirical evidence exists to forecast the amount of tax revenue needed to accommodate the wage increase, the fiscal sustainability of the new wage rate is uncertain given the limited progress made on increasing tax revenue in Nigeria.

Economic Responses

Sustained Inflationary Pressure

In theory, businesses are forced to raise prices when there is an increase in minimum wage, and this ultimately places cost-push inflationary pressures on the economy. Real business practices conform with this theory. A strategic attempt to absorb increasing labour costs tend to cause producers to transfer the cost of wage increase to product prices, which are eventually borne by consumers in form of higher prices. For example, in 2003 when the government reviewed a wage increase, prices of goods and services rose, and inflation rate spiked from about 10.5% to as high as 24%. A similar wage-increase in 2011 saw the inflation rate remain at double-digit for two years thereafter, according to data from the CBN. If implemented, the 2019 wage increase may cause inflation rate to extensively exceed the CBN’s 12% projection and gradually erode purchasing power and value of the new minimum wage in the long term. By then, the cycle of agitations for another wage raise may come into effect, yet again.

Possible job losses

Empirical evidences such as from the World Bank, suggest that employment effects of a rise in the minimum wage are often significant and negative, particularly in a largely informal labour market like Nigeria. By reorganizing internal human resource structure, businesses that lack the capacity to keep up with an increase in overhead costs may take drastic measures such as retrenching workers and downsizing labour time. With a number of job losses and layoffs, unemployment and underemployment rates are forced to increase. A survey by the NBS showed that between 2011 when there was a rise in minimum wage and 2012, about 1.43 million people who were fully employed or underemployed lost their jobs. Although there was an increase in the labour force population, the total number of unemployed persons rose by 82.5% to 7.3 million. It is likely that the implementation of the 2019 approved minimum wage may project a similar trend given past occurrences.

Going Forward:

Although revenue from taxation has grown over the years, efforts of the government and revenue generating agencies to improve tax revenue have yielded limited progress. While collection processes have improved, other areas for improvement exist such as limited tax coverage that mitigates the collection efforts. To ensure that efforts yield the much-needed progress and beyond the existing collection process, widening Nigeria’s tax net is absolutely necessary. Lagos state sets a remarkable example for other states to follow through its model tax administrative machinery. The machinery granted full autonomy to the Lagos State Inland Revenue Service in 2006 and created new tax operational units within the agency. In 2008, the agency introduced the self-assessment filling system and a system for collaboration with other MDAs. To capture a wider range of the informal sector, in 2016, tax assessments were translated to various local languages, and more than 39 tax stations had been established across the state with compliance initiatives as priority. As a result of the wider coverage, Lagos state has witnessed unprecedented IGR growth – from a monthly average of N5.1 billion in 2006 to N56.7 billion in 2018. Going forward, states whose tax agencies lack such machinery should first be granted autonomy by the state governments. Further, capturing a wider range of informal sector in each state and at the federal level through similar initiatives is vital to adding more taxpayers into the tax net.

Individuals and businesses are not left out in ensuring that the new minimum wage policy works for the improvement of the economy. To do this, critical emphasis on employee/worker productivity is essential, particularly when the alternative retrench mechanism is not an option. For individuals: collecting a higher wage is needful to encourage their improved commitment and performance. For businesses: given that productivity is an important determinant of economic growth, spurring productivity could inform higher national output. More regular assessments and demanding increased realistic targets from each employee are imperative measures that could be used to ensure improved productivity among workers and employees.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China

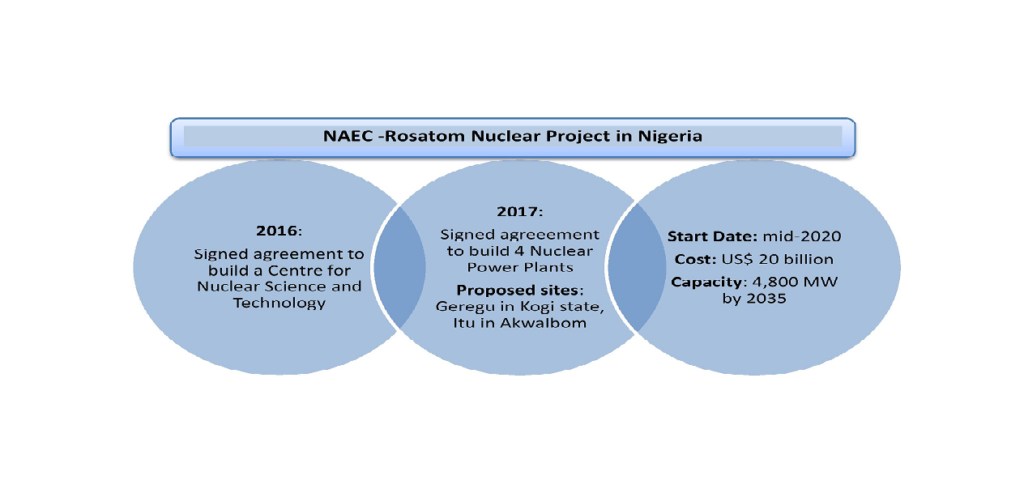

In light of the nuclear power development, two key questions call for objective analysis:

In light of the nuclear power development, two key questions call for objective analysis: