Prospects for Building Fiscal Buffers to Manage Unprecedented Shocks in Nigeria

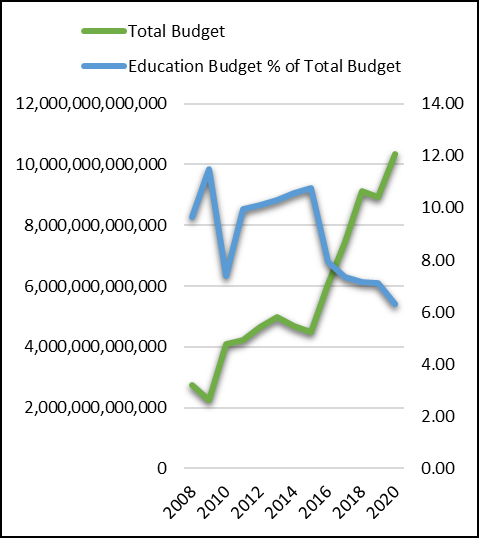

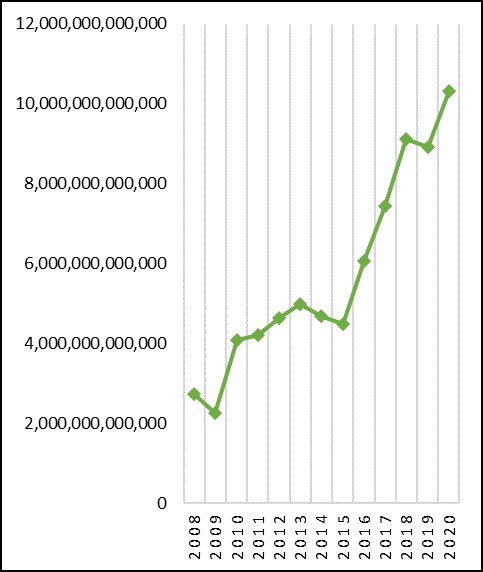

The outbreak of the Coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic was accompanied by an unprecedented shock, with colossal impact on economic activities worldwide. One of the major effects is the global economic lock-down implemented to curb the widespread of the pandemic. Nigeria as an oil-dependent nation, also experienced an external shock as a result of the oil price crash. The combination of these twin shock (covid-19 pandemic and oil price shock) worsened the scenario in Nigeria. For instance, government forecasted a decline in oil revenue flow from 5.5 trillion Naira to 1.1 trillion Naira in 2020. Thus, due to these shocks, Nigeria is faced with a sudden fiscal crisis combined with other colossal effects. The effect of these twin shocks will vary across countries due to a number of factors among which the quality of fiscal space will be crucial.

Over time, Fiscal buffers have proven to be indispensable in enhancing macroeconomic resilience to external shocks by preventing them from plunging into financial strain. Meanwhile, the Excess Crude Account (ECA) was created in 2004 in order to save excess of the budgetary benchmark that will be generated from the sale of crude oil account. It was created to serve as an absorber of shocks caused by oil price volatility with the aim of protecting Nigeria’s budget from unprecedented shortfalls.

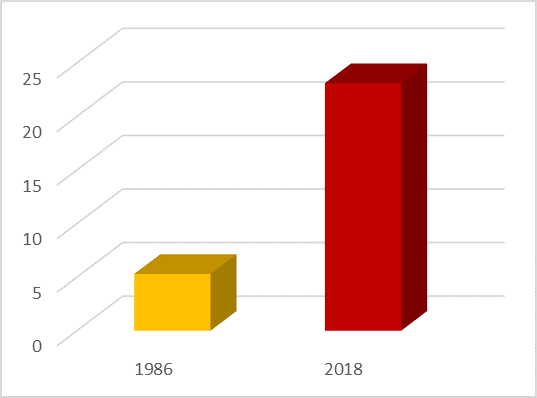

The ECA also serves as a buffer for public expenditure from being distorted by business cycle or waves, triggered by international oil markets. Since its inception (2004), the ECA has been taking an ascending trend until 2010 when it declined due to the financial crisis of 2007-2009. As at April 2018, the ECA account stood at $1.8 billion which declined to $324.9 million as at January 2020. It became quite daunting as the account deteriorated and further slumped to $71.8 million dollar within the range of 5 consecutive months (January 2020 – May 2020). Notably, the depletion of the ECA has a ripple effect on the economy, as it reflects not only the absence of funds that will serve as a buffer to another wave of recession, but also intensifying Nigeria’s economy, making it more vulnerable to external shocks.

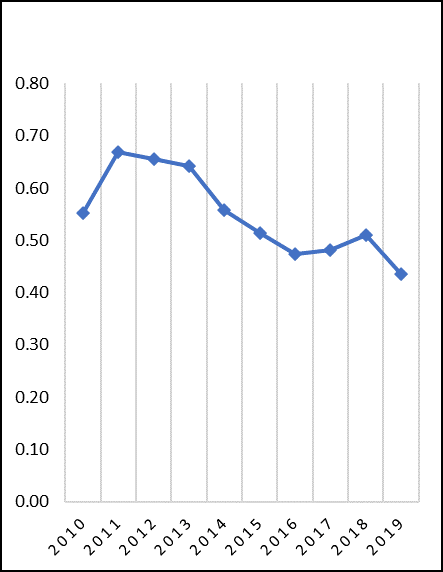

Consequently, some loopholes were identified with the running of the ECA, which includes; lack of transparency and non-legal backing. Hence, in 2011, the Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) was created to amend the disagreements surrounding the ECA. The SWF comprises three categories of funds with visibly stated objectives. They include; the stabilization Fund, the Future Generations Fund as well as the Nigeria Infrastructure Fund. So far, Nigeria has invested only $2.53 billion in the SWF between 2012-2019. While the Stabilization fund of the SWF serves the same purpose with ECA, only 20 percent accounts for the fund, while the future generation fund and Nigeria infrastructure fund justify the remaining 80 percent. As at December 2019, the Stabilization Fund which ought to serve as buffer to economic shocks was reported to have only $351 million. However, in April 2020, a withdrawal of $150 million was granted by the federal government to serve as a supplement to the government’s Federation Accounts and Allocation Committee’s disbursements for allocation to the 3 tiers of government. This brought down the balance of the SWF to the total amount of $201 million, a far cry from $0.5 billion.

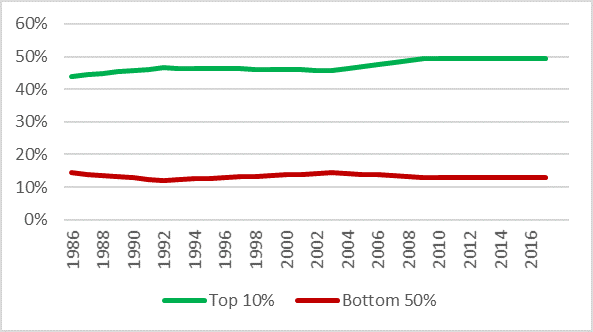

Furthermore, Nigeria’s growth rate is forecasted to plunge to -3.4% in year 2020 which by indication is worse than the growth rate of -1.6% when Nigeria experienced recession in 2016. The bottom line is the nation is distressed with a double shock from Covid-19 pandemic as well as dwindling oil price. This scenario was more aggravated by the fact that the buffers that were created to absorb these forms of shocks have not been effective. While the ECA is faced with a hitch of depletion, the SWF is faced with problems of low savings. Accordingly, the World Bank stated that, “External balances are fragile to hot money movements, and fiscal buffers are exhausted, making Nigeria’s economy vulnerable to external risks”. Therefore, the absence of a strong buffer to these shocks will only push the economy to another wave of recession with a more difficult recovery path. As a result, the prevalent scenario will continue to constrain the budget envelope, consequently limiting its fiscal space.

Building Fiscal Resilience: Some Policy Suggestions

The incidence of these scenarios – the Covid-19 pandemic and the plunge in crude oil price underscores the need for government to look inward to build more fiscal resilience or fiscal buffers that would absorb any unprecedented shocks. Many countries around the world, including Nigeria, are now faced with massive instability, and if a next wave of recession hits the global economy, most countries will not be able to recover without sufficient buffers.

It is therefore imperative for Government to take a deep look at how to save and invest more in critical infrastructure that will generate substantial revenue. The following are viable solutions that can help build fiscal buffers and economic resilience in both the short and long term.:

Prudent Management of Funds

There are criticisms surrounding the use of the ECA funds in particular. Its lack of legal support and proper structure has made it subject to urgent and inadequate withdrawals. Likewise, the ECA does not have sufficient debit and credit records as well as conforming withdrawals or approvals for these withdrawals This has mandated the incorporation of the ECA with the SWF since the latter has covered the identified loopholes of ECA and is doing even better despite meager funds under its authority. The accounts should be treated prudently, of the utmost importance. Withdrawals of funds should be restricted and made only exigent reasons such as the recent economic situation.

Ultimately, the federal government needs to look inward and adopt a more judicious spending regime, improve efficiency to guard against waste and deploy more technology, it is often cheaper and innovative, so it can generate new opportunities.

Structural Reforms

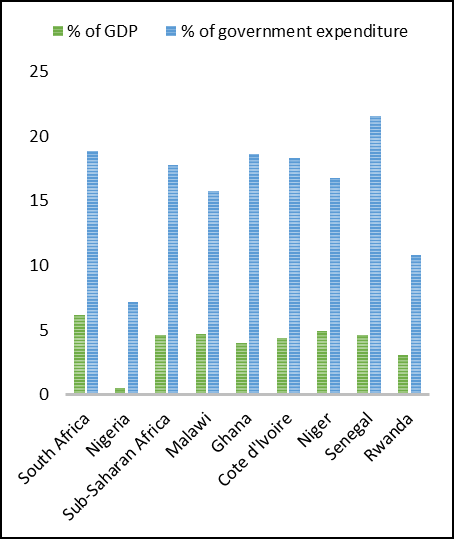

Fiscal reforms are of paramount importance in this situation. The government needs to intensify and embrace structural reforms to build an efficient institutional and policy framework to manage the volatility of fluctuations in the oil sector fluctuations, in order to sustain the growth of the non-oil sector. More importantly, unwavering reforms that have a significant impact on the trajectory of the economy, such as the removal of subsidies, elimination of forex and trade restrictions, greater transparency and predictability of monetary policy and increased domestic revenue mobilization should be put in place. These Structural reforms will attract private investment, given that private investment serves as an engine growth for the economy as well as a good fiscal stimulus, and will therefore stand as good resilient in absorbing shocks. In 2019, Nigeria ranked 131 among 190 economies in the Ease of Doing Business. This result is quite daunting looking at the prominence of business in an economy. As a stabilizer of many macroeconomic variables as well as a driving factor of the economy, it becomes very vital for government to vigorously implement responsive policies to support the expansion of businesses.

Intensify Economic Diversification

The recent events in the Nigerian economic performance especially the effects of the twin shocks re-echoes how important it is to diversify the Nigerian economy .Economic diversification has unlimited potentials to increase Africa’s resilience to external shocks as well as influence the attainment of its economic growth and development. Although, some actions have been taken to diversify the Nigerian economy from excessive dependence on crude oil to development in the non-oil divisions, Nigeria is still inexperienced as far as diversification is concerned. This is because it is not enough to invest in a particular sector and abandon it. There is a need for constant follow up and the formulation of appropriate policies in place to ensure that the sector develops to a desired point.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China