The role of Industries Without Smokestacks (IWOSS) in addressing Nigeria’s unemployment crisis

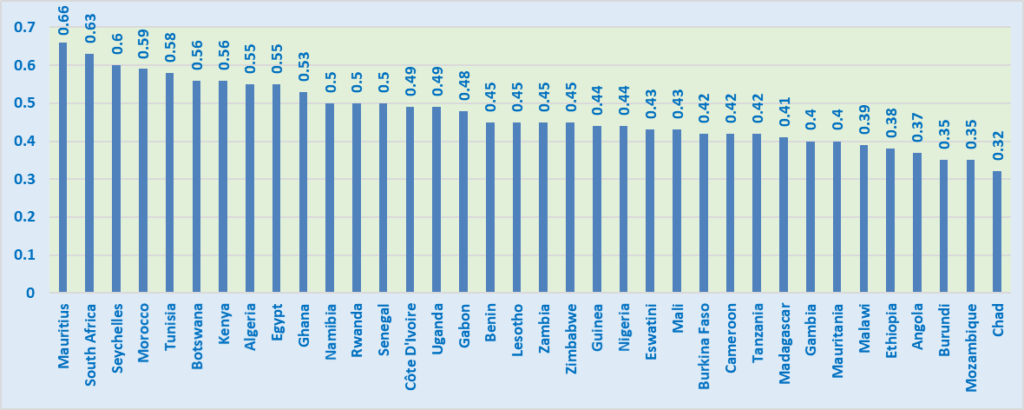

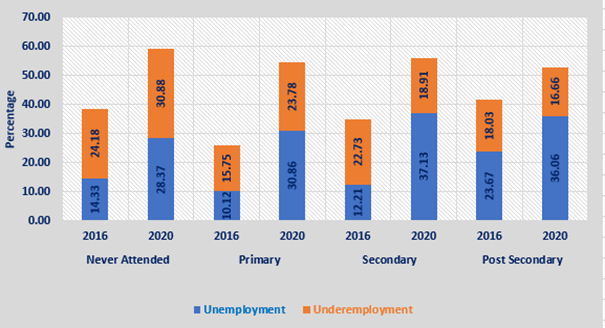

In 2020, Nigeria’s population was estimated to be above 200 million and about 61 percent (122 million) of the population were within the working age. Out of the 122 million in the working age group, 69.7 million are in the labour force and a significant proportion of them are without a job. The most recent unemployment statistics (2020Q4) shows that 33.3 percent of the labour force are unemployed and another 22.8 percent are underemployed. The situation is, however, worse for the young population (those between the ages of 15 and 34 years) as 42.5 percent are unemployed and another 21 percent are underemployed. Similarly, the unemployment situation is higher among those without education as well as those with minimal education as the unemployment rate among those that have not attended school and those with primary school education is 31 percent and 24 percent respectively, relative to 17 percent for those with post-secondary education (see Figure 1). With Nigeria’s population estimated to reach 250 million people by 2030, the unemployment situation is increasingly drawing the attention of relevant stakeholders as the country’s ability to create sufficient jobs for new entrants as well as those in the labour market is undermined.

Figure 1: Unemployment in Nigeria by Level of Education

Source: Authors’ computation from National Bureau of Statistics

IWOSS: the potential solution

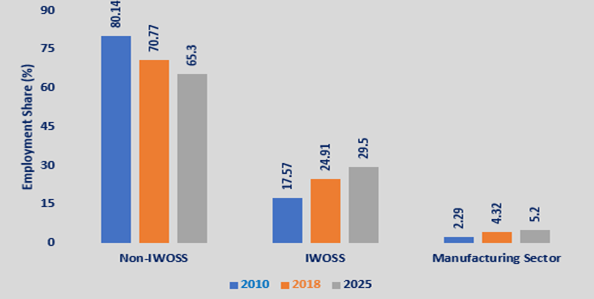

The sluggish growth of Nigeria's manufacturing sector, which otherwise would have absorbed labour, has limited employment creation in the country, as it has in many other African nations. Recent studies highlight alternative industries, referred to as "industries without smokestacks'' (IWOSS), that have many similarities to manufacturing including their tradability, propensity to absorb significant numbers of low-skilled labour, potential to significantly contribute to output, and high productivity. Industries without smokestacks include tourism, horticulture, business services, trade, transportation and logistics, and some information and communication technology (ICT)-based services. In Nigeria, the IWOSS sector is quickly gaining prominence and contributing increasingly to employment from 17.6 percent to 24.9 percent of total employment between 2010 and 2018 (see Figure 2). Hence, the development of the IWOSS sector has the potential to generate an appreciable number of employment opportunities for Nigerians, especially the youths.

Figure 2: Employment in Nigeria: IWOSS and Non-IWOSS

Source: Authors’ calculation based on GDP estimates from the National Bureau of Statistics

IWOSS sectors: employment creation channels

Despite the role of IWOSS sectors in delivering jobs for the population, employment creation in the IWOSS sector is premised on three factors. First, the transition towards climate friendly activities will create new jobs. Also, technological advancement is resulting in new forms of jobs that were not in existence two decades ago and traditional jobs are eroding. Finally, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is expected to increase the growth of new industries in African countries including Nigeria as well as increase demand for the services of existing ones.

Industries without smokestacks (IWOSS) by definition are low CO2 emitting industries. In CoP26, there was a renewed commitment by countries including Nigeria to net zero carbon emissions by 2063. In line with this pledge, Nigeria’s National Development Plan included the green economy as part of the five trends that would shape the world in the next decade. As a result, the Plan provided strategic support for the expansion and emergence of environmentally friendly industries. For instance, the Plan projected the increased use of smart techniques in agriculture. Simply put, commitment towards net zero carbon emissions would lead to the winding down of existing jobs and emergence of new jobs particularly jobs in industries that support the green economy. On this basis, government and business leaders are already making concerted efforts to create new industries that are environmentally friendly.

Moreover, structural change is taking place globally and these changes reflect the impact of technological progress and a changing global marketplace prospect of industrialization. The World Economic Forum identified five high in-demand roles, which are (i) IT and data, (ii) sales and marketing, (iii) operating and logistics, (iv) manufacturing and production and (v) customer facing and front office. Four out of the five identified job roles are related to IWOSS thus, indicating that the job of the future would be found in IWOSS. These opportunities IWOSS offers could be tapped into and accelerated if the Nigerian government amends policies to pave the way for greater investments into the IWOSS sector.

Nigeria has long sought to increase its industrial capacity as a way of harnessing the benefits presented by the AfCFTA, generating employment opportunities, and stimulating GDP growth. The IWOSS sector presents exciting earnings that are geared towards expanding Nigeria’s industrial capacity. The AfCFTA, which was launched on January 1, 2021, integrates 54 of the 55 African Union members, creating a market with a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion. It aims to create a single market for goods, services, and the free movement of labour, and it intends to abolish tariffs on 90 percent of the goods produced in the region. The implementation of the agreement is expected to enhance cross-border financial transactions, expansion of the agro-processing businesses, and increase the demand for transportation and logistics services. Significant number of jobs are expected to be created in these industries with implementation of supportive policies in line with the AfCFTA.

Imperative for Nigeria: the four C’s

To leverage the employment potential of the IWOSS sectors in addressing Nigeria’s employment challenges, these sectors require support from the government. Four ways have been identified through which IWOSS sectors can be supported.

Competitive educational system

In Nigeria, the educational system is underperforming and less competitive. As a result, the students are poorly prepared for the in-demand skills. Except for a few educational institutions, the curriculum which serves as a manual that guides teaching are rarely updated. This phenomenon occurs at every level of education and in part explains the existing skills mismatch between the skills demanded by employers and the skills profile possessed by students graduating from educational institutions. The magnitude of the problem is high due to limited collaboration and coordination between educational and training institutions as well as various industries.

The government needs to provide a framework that strengthens the flourishing of a competitive education system. This is important in ensuring that students are taught in-demand skills. In other words, the educational system prepares the students with skills necessary for them to be competitive in the job markets. Also, the learning structure includes internship positions to intimate the students with industry demands.

Commitment to improvement in infrastructure

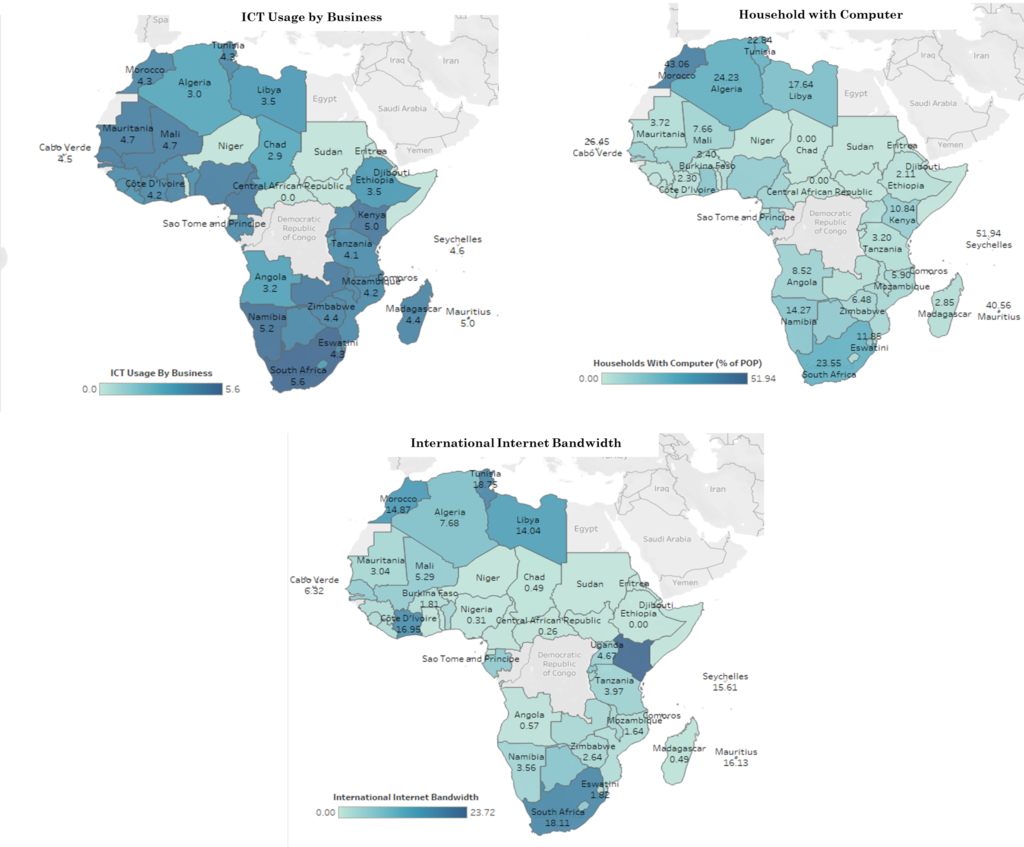

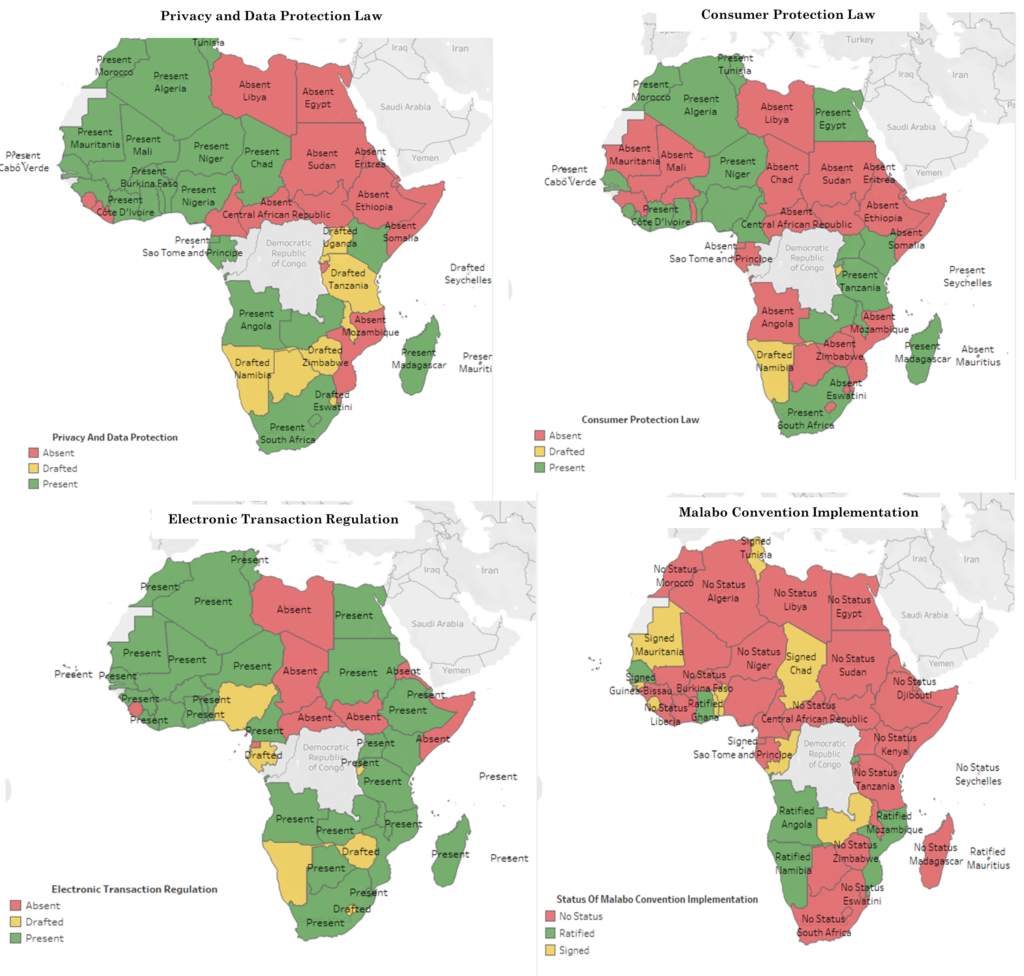

Nigeria’s infrastructural deficit is enormous and constitute a drag to economic growth and development. Recent evidence suggests that Nigeria still lags and needs to intensify efforts to improve its digital economy. In Nigeria, digitization opportunities are limited in a variety of ways. Some are the result of deficiencies in digital infrastructure and digital skills, while others relate to how the digital economy is controlled. In other words, the existing deficiency in digital infrastructure has constrained the competitiveness of Nigeria's e-commerce and logistics business, thereby lowering the extent to which they can expand, and suggesting that there are ample rooms for growth. In addition, the power and transportation are grossly inadequate and affects the efficiency of firms. Commitment to improve infrastructure should therefore include the power and the transportation infrastructure. The power sector infrastructure should aim at simultaneously expanding the country’s power generating capacity and transmission. Similarly, the investment in transportation is crucial in reducing congestion at port and commuting time, which indirectly increases the cost of doing business in the country. These interventions can transcend to positive IWOSS sector productivity. Governments, policymakers, and key stakeholders should collaborate to increase investment in infrastructure.

Coordination of climate actions

The Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals emphasised environmental sustainability when describing economic growth. As a result, the direction has shifted from economic growth to sustainable growth or a green economy. While the green economy was incorporated in the National Development Plan, the government needs to create a structure that will ensure that the private sector acts in a coordinated way. In other words, the activities of the private sector targeted at achieving net zero carbon emissions needs to be coordinated to prevent repetitive activities and optimise actions towards achieving the goal. For instance, the government has to work more closely with the private sector and research institutions in creating knowledge aggregating platform and events to ease the dissemination of climate related information. These platform and events would create opportunity for different actors working on climate change adaption and mitigation strategies to have up-to-date information on new development, especially those within the country.

Creation of innovative financing options for MSMEs

Small businesses are the engine of economic growth and are very crucial in fostering job creation in the IWOSS sector. Recent evidence suggests that, in 2020, Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) constitute about 96.9 percent of total number of businesses and contributes about 46.3 percent of the total GDP. However, their growth has been hindered by lack of access to finance with significant share of small business owners relying on their personal savings and borrowing from friends and family to support business operation. Small businesses account for less than 5 percent of commercial bank credit, which contributes in part to their financing gap estimated at about N617.3 billion annually. While there are existing funding schemes targeted to MSMEs, their scale of operation is very limited. Addressing financing gaps among the MSMEs is crucial in optimising their contribution to job creation, otherwise, firms with potential remain small or die within few years of establishment. The Development Bank of Nigeria, Central Bank of Nigeria, and Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency of Nigeria need to partner with financial institutions to design additional innovative financing schemes (and expanding already existing ones) that would provide MSMEs with finance at scale and at affordable rate. The financing scheme should be designed in a form of cooperative structure such that the beneficiary of the funds is accountable to other cooperative members.

Conclusion

In the National Development Plan, 2021 - 2025, the Nigerian government aims to create 21 million jobs by the end of 2025 through the private sector. This article makes a case about the capacity of the IWOSS sectors in driving employment creation in Nigeria, and the need to prioritise it. While the evidence about the IWOSS sector in Nigeria is scarce, this piece highlights the potential of the sector in addressing the employment crisis in Nigeria. As a result, the article notes four imperatives to upscale the impact of the IWOSS sector. They are (i) competitive educational systems, (ii) commitment to improvement in infrastructure, (iii) coordination of climate change actions, and (iv) creation of innovative financing options for SMEs. These actions would go a long way toward enabling the IWOSS sectors to catalyse employment creation.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China