How Big is Nigeria’s Power Demand?

Context: Nigeria has Africa’s largest population and economy, but Nigerians consume 144 kwh per capita annually, only 3.5% as much as South Africans.1 With only 12 GW installed, and typically just one-third of that delivered, Nigerian power production falls far short of demand, which is a primary constraint on economic growth. Self-generation using dirty diesel generators is exceedingly common in Nigeria, and bear a significant economic and environmental cost.2 But exactly how big is the demand-supply gap? And what does future demand look like?

How large is power demand in Nigeria?

Electricity demand estimates and projections for Nigeria suggest that demand is already substantial and increasing rapidly due to population and income growth.

- Nigeria is one of the most underpowered countries in the world, with actual consumption 80% below expectations based on current population and income levels.3

- Peer countries consume far more electricity per capita than Nigeria does currently. Ghana consumes over twice as much, Tunisia over ten times, and South Africa almost thirty times as much.

- Self-generation in Nigeria is extremely prevalent; nearly 14GW capacity exists in small scale diesel and petrol generators, and nearly half of all electricity consumed is self-generated. This implies a huge unserved demand.

- Due to a population boom and a large gap in electrification, the World Bank projects electricity demand will have grown by a factor of over 5 between 2009 and 2020, and 16.8 by 2035.4

Given this, we can assume that Nigeria’s demand gap is significant, though exactly how large is disputed. The significant differences in these estimates demonstrate the difficulty, and importance, of accurate demand forecasting.

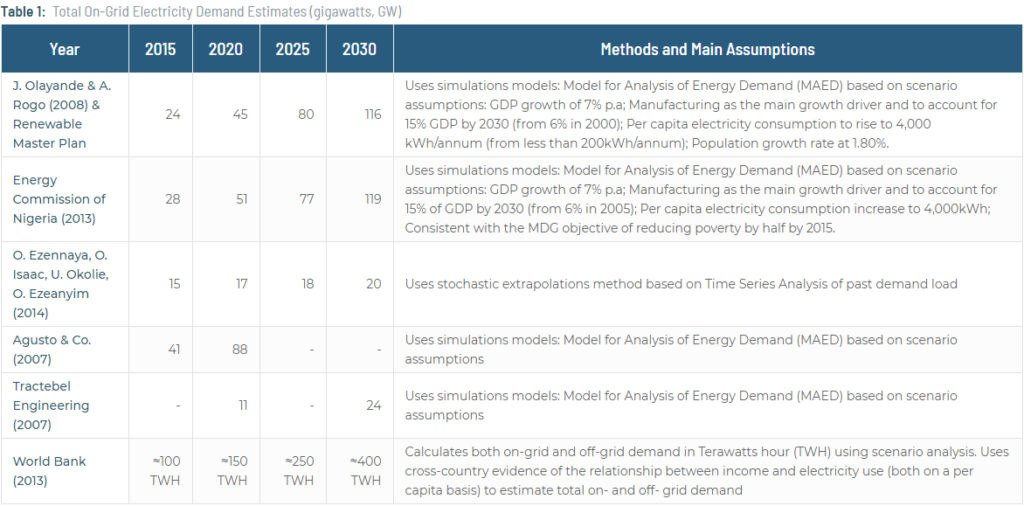

The below estimates show large variance in projections for peak power demand mainly due to differences in scenario assumptions and existing infrastructure during study periods. Projecting power demand in Nigeria is challenging due to difficulty in estimating the large amount of electricity produced by small and unregulated petrol/diesel-powered generators, and in quantifying suppressed demand. Looking at available demand estimates for 2015 (Table 1), Nigeria’s on-grid electricity demand seems to be about 4 – 12 times the total electricity distributed on the grid (at 3200 MW, or 3.2 GW). Even at optimistic capacity factors and assumptions about deliverability, Nigeria needs well over 63GW of new generation to satisfy unmet demand.5 Until then, expensive and dirty self-generation will remain pervasive.

Endnotes

- World Bank (2019). Electric Power Consumption (kWh per capita). Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=NG

- IEA (2017), Energy Access Outlook: From Poverty to Prosperity, IEA.

- Todd Moss and Gailyn Portelance. “Do African Countries Consume Less (or More) Electricity than Their Income Levels Suggest?”

- R. Cervigni, J. Rogers, and M. Henrion (2018), Low Carbon development: Opportunities for Nigeria, The World Bank

- GIZ (2015), The Nigerian Energy Sector An Overview with a Special Emphasis on Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Rural Electrification. Nigerian Energy Support Programme (NESP)

- Olayande, J.S & Rogo, A.T. (2008), Electricity Demand and Supply Projections for Nigeria, Abuja: Energy Commission of Nigeria

- Sambo, A. S., 2008. Paper presented at the “National Workshop on the Participation of State Governments in the Power Sector: Matching Supply with Demand”, 29 July 2008, Ladi Kwali Hall, Sheraton Hotel and Towers, Abuja.

- O. Ezennaya, O. Isaac, U. Okolie, O. Ezeanyim (2014), Analysis Of Nigeria‘s National Electricity Demand Forecast (2013-2030), International Journal Of Scientific & Technology Research 3(3)

This article was first published on Energy for Growth Hub

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China