Nigeria, often referred to as “Africa’s giant”, has experienced a complex trajectory of development and poverty reduction which presents a paradoxical scenario (World Bank, 2022). Despite being the continent’s largest economy, Nigeria’s annual growth rate has been declining since the early 2000s while poverty remains a pervasive challenge (World Bank, 2022). Evaluating the progress made in reducing poverty and promoting development, and analysing the reasons behind any setbacks, is key to gaining some insights into the country’s prospects, and helps provide valuable lessons to be learned from Nigeria’s case study.

This commentary was first published by the Italian Institute for International Political Studies

The pandemic undermined the progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. The prosperity of the Global South, including Nigeria, depends on universal quality education at the foundation level. This article highlights how the pandemic reversed the gains realised since 2015. It describes how technology and partnership could help build back the educational sector to achieve inclusive quality learning.

Educational inequality describes the disparity in education opportunities among socio-economic, regional, and cultural groups. In Nigeria, for example, the school completion rate among children from wealthy households and the southern region is 63% and 34% higher than those from low-income families and the northern part. Such educational inequalities contribute to widening disparity in opportunities. People with low or little education are more likely to work in the informal sector and low-wage employment.

This Blog was first published here by the Southern Voice.

I recently had the privilege of sharing my experiences on advancing data justice in African states, during an expert workshop organised by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) where I represented the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa. The workshop’s theme centred on 6 pillars to guide the conversation around data justice: power, participation, equity, access, knowledge and identity.

At CSEA, we commenced a research and advocacy project back in 2020 to advocate for a stronger data governance landscape in the region, as a means of putting in place necessary frameworks that can build trust in the digital and data economy, particularly in the context of regional trade, to ensure inclusive growth. Consequently, when we think about data justice, it is usually in terms of social justice, such that no one is exploited but rather everyone, not just a few, can benefit equitably from the opportunities that the data economy offers.

For this reason, CSEA has been clamouring for effective data regulation. However, we have observed some emerging trends that could pose a risk to encouraging data justice under two of the guiding pillars – power and participation.

Risk of power imbalance

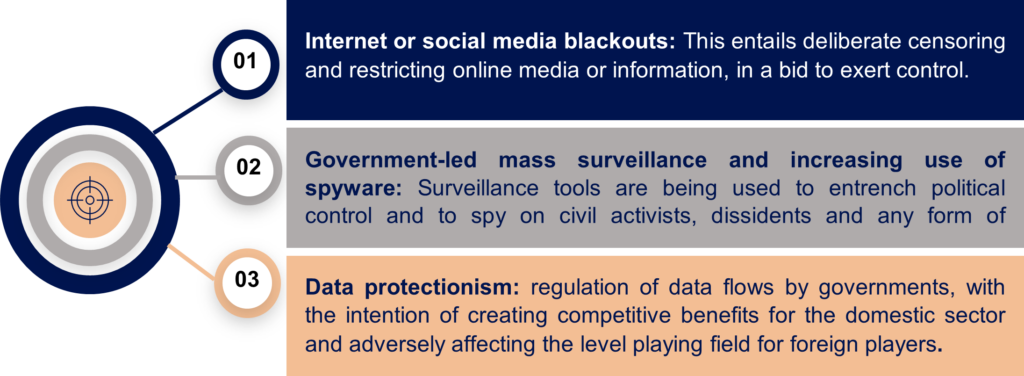

For effective data governance, there needs to be a balance of power between the different players in the ecosystem, including the data subjects. However, there is a real challenge of effectively balancing data regulatory approach(es) in a manner that does not result in over-regulation of data or state abuse of regulatory powers. The figure below highlights some of these trends observed across the region:

Source: CSEA (2022) - Curtailing State Extremism In Data Governance

The above can have counter-productive implications including; human rights violation on freedom of speech and association, heightened distrust, deprivation as a result of loss of livelihoods, a potential barrier to market entry for small firms, and increased uncertainty and costs for foreign investors making it unattractive to do business in such markets. Some countries have data localisation provisions that restrict data transfers beyond their borders. This can impair regional trade integration and the development of appropriate artificial intelligence systems which require vast amounts of data.

There is also a risk of power imbalance between African nations as it relates to data. CSEA’s Digital Preparedness Index shows that African countries are at varied stages of implementing data governance laws and frameworks. Only a few countries in the region are currently able to benefit from the rapid development of the data economy. Less digitally mature countries in the region are at risk of being left behind, due to the huge investments and resources needed to support an effective data regulatory mechanism. Inequality in human resource capacity affects countries’ ability to establish good data governance rules. Policymakers oftentimes, do not fully understand technological development to be able to adopt rules that steer rather than prevent innovation.

Inadequate public participation in data governance

Public participation in data governance is key to re-balancing power structures. For policymakers to effectively protect citizens’ data rights, extensive collaboration with, and input from the persons being protected is required. This goes beyond simple consultations on draft data policies or legislation. It entails the active involvement of the public in the policy vision, development and implementation of data governance frameworks. In reality, how can the public take an active role in data policy processes and decision-making when they are not fully aware of their rights and responsibilities and lack adequate knowledge on issues related to data governance? There is definitely scope for countries to commit to empowering citizens to engage in deciding how their data is governed.

As organisations like CIPESA and CSEA continue to advocate for increased data justice, some practical issues to ponder on and work towards finding solutions are:

Persistently high levels of unemployment have emerged to become a key policy challenge in Nigeria. Between 2010 and 2018, the unemployment rate rose from 5 percent to 23 percent. Worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, the economy is simply not generating enough jobs for labor entrants, particularly women and youth. In 2020, the national unemployment rate stood at 33 percent, while 52 percent of women remained unemployed and 42 percent of youth (aged 15-34 years) were without jobs.

Moreover, the contribution of the manufacturing sector to formal sector employment has also been low and stagnant, averaging 11.4 percent between 2011 and 2021. Estimates show that Nigeria’s manufacturing sector accounts for less than 10 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), and as a result, the sector employs only a small proportion of the labor force.

Given that traditional sectors like manufacturing alone can no longer sustain economic development and generate sufficient job opportunities, attention is now shifting toward alternative sectors that can support growth and create jobs, for example: agro-processing, financial and business services, information and communications technology (ICT), tourism, formal trade, and transport. These “industries without smokestacks” (IWOSS)—as they have been termed in a growing body of literature—are often service-based sectors that closely mimic manufacturing in their tradability, proclivity to absorb large numbers of low-skilled employees, and potential for technological change and productivity growth.

In our recent report, published jointly by the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings and the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa, we find that these industries without smokestacks are indeed already surpassing manufacturing and other traditional sectors in creating jobs and generating economic growth in Nigeria.

Nigeria has a population of over 200 million people and is one of the largest producers of tobacco in Africa. However, Nigeria faces significant challenges in achieving food security. With a growing population, there is a need for Nigeria to prioritise food production over tobacco farming. This is because about 40 percent of Nigerians are food insecure, and prioritising food production will help ensure that there is enough food to meet the needs of the population, particularly vulnerable groups such as women and children.

Tobacco is not a staple food item, and its demand is highly contingent on external factors such as global tobacco consumption, market prices and health regulations. In addition, tobacco farming is frequently linked to deforestation, soil erosion, and water contamination, which can result in detrimental environmental and public health outcomes. Prioritising food production over tobacco cultivation can have substantial environmental benefits, as the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices can help facilitate soil preservation, enhance biodiversity, and ecosystem services, while concurrently augmenting crop yields and decreasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Transitioning from bitter harvest to more nutritious food for all.

Nigeria has a long history of tobacco farming and is currently one of the leading producers of tobacco in West Africa, with about 4,700 metric tons produced in 2021. However, this practice has negative impacts on food security, especially for smallholder farmers who depend on subsistence agriculture. The share of tobacco in crop production in Nigeria may be modest and can vary from year to year but a shift away from tobacco farming can still contribute to achieving food security in Nigeria. The competition for fertile land, water, and other resources between tobacco and food crops reduces the land available for food production, worsening food insecurity. Moreover, tobacco farming frequently involves the use of hazardous chemicals such as pesticides and fertilisers that contaminate the soil, water, and food crops. The use of these chemicals also poses a risk to the health of farmers and their families, as well as consumers.

Economic and health benefits of prioritizing food production over tobacco farming.

1. Food Security and Basic Human Needs

Food security lies at the heart of human survival and well-being. Nigeria’s population is steadily increasing, therefore, providing an adequate and sustainable food supply is critical. By prioritizing food production, we address the fundamental need for sustenance, with the goal of eliminating hunger and malnutrition, which still affects millions of Nigerians.

Redirecting resources from tobacco farming to nutritional crops will contribute to the availability, accessibility, and affordability of food, thereby securing the basic human right to an adequate diet.

2. Public Health and Well-being

Tobacco consumption has been linked to a myriad of preventable diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular ailments, and respiratory disorders. By shifting our focus towards food production, the health and well-being of individuals and communities is prioritized. A reduction in tobacco cultivation will lead to a decline in smoking prevalence, subsequently lowering the incidence of tobacco-related illnesses. This shift offers an opportunity to promote healthier lifestyles, emphasizing the importance of balanced nutrition and fostering a culture of well-being.

3. Economic Advantages and Sustainable Development

The economic benefits of prioritizing food production over tobacco production are significant. Agriculture and food-related industries have the potential to create jobs and stimulate local economies, particularly in rural areas. An increase in agricultural investment can boost productivity, generate income for farmers, and foster rural development. Moreover, this redirection of resources does not necessarily lead to economic losses. Alternatives to tobacco farming, such as diverse crops or sustainable agricultural practices, can be explored to ensure a smooth transition to a more economically viable and sustainable model.

4. Environmental Sustainability and Conservation

Tobacco cultivation places a substantial burden on the environment. It requires extensive land use, contributes to deforestation, degrades soil quality, and consumes vast amounts of water and chemical. By prioritizing food production, we can utilize land more efficiently, thereby reducing deforestation and preserving natural habitats. Sustainable agricultural practices can be adopted, which will help promote soil health and conservation. Furthermore, shifting away from tobacco cultivation reduces the pollution caused by pesticides and chemicals, resulting in cleaner water sources and a healthier ecosystem.

5. Social Equity and Inclusive Development

Prioritizing food production fosters social equity by addressing the basic needs of all individuals. Food is a universal requirement, and access to nutritious food is essential for human development. By focusing on ensuring food security for all, we work towards creating a more equitable society where no one is left behind. This shift aligns with the principles of social justice, promoting inclusivity, and reducing inequalities based on access to vital resources.

Policy implications

The transition from tobacco to food production represents a significant shift with numerous benefits for society. Policymakers play a vital role in facilitating this transition by implementing supportive measures and creating an enabling environment, emphasizing the need for effective policies, incentives, and collaborations to achieve sustainable and successful outcomes.

i. Crafting and Implementing Supportive Policies

Policymakers are responsible for developing and implementing policies that encourage the transition from tobacco to food production. This involves a comprehensive assessment of the local, regional, and national agricultural landscapes, taking into consideration factors such as soil suitability, climate, and market demand. Policymakers can use measures such as subsidies, grants, and tax breaks to incentivize farmers to shift their focus to food crops . To facilitate the process and ensure a smooth transition, clear regulations and guidelines should be set, while also addressing potential challenges and mitigating risks.

ii. Strengthening Agricultural Infrastructure and Extension Services

To support the transition, policymakers need to invest in strengthening agricultural infrastructure and extension services. This includes improving irrigation systems, upgrading storage facilities, and providing access to modern farming technologies. Additionally, policymakers can allocate resources for the development of extension services that provide farmers with the necessary knowledge, training, and support to adapt their practices to food production. By enhancing the infrastructure and support systems, policymakers enable farmers to maximize productivity and successfully transition to food cultivation.

iii. Promoting Research and Development

Policymakers play a crucial role in promoting research and development (R&D) efforts focused on sustainable food production. This includes allocating funds for agricultural research institutions and universities to conduct studies on crop diversification, climate-resilient farming techniques, and efficient resource management. Policymakers can also encourage collaboration between researchers, farmers, and industry stakeholders to develop innovative solutions and technologies that improve food production. By fostering R&D, policymakers contribute to the knowledge base necessary for successful transitions and create avenues for continuous improvement in the agricultural sector.

iv. Facilitating Market Access and Value Chain Development

To successfully shift from tobacco to food production, it is crucial to ensure access to markets and build strong value chains. Policymakers can support farmers by facilitating connections with buyers, processors, and retailers, both locally and internationally. This can be achieved by creating platforms for market linkages, supporting the establishment of cooperatives, and promoting fair trade practices. Policymakers can also assist in developing value-added processing industries, enabling farmers to enhance their income by diversifying their agricultural products and accessing higher-value markets.

v.Engaging Stakeholders and Promoting Collaboration

Policymakers play a critical role in fostering collaboration and engagement among various stakeholders involved in the transition process. This includes farmers, agricultural associations, researchers, non-governmental organizations, and private sector entities. Policymakers can organize forums, workshops, and consultations to facilitate dialogue and knowledge sharing. By creating a platform for collaboration, policymakers can leverage the expertise and resources of different stakeholders, ensuring a comprehensive approach to the transition and maximizing its positive impact.

Conclusion

The need for Nigeria to prioritize food production over tobacco cannot overstated. Redirecting resources, efforts, and policies towards nourishing crops and sustainable agriculture will have far-reaching benefits for humanity. It ensures food security, promotes public health and well-being, stimulates economic growth, fosters environmental sustainability, and advances social equity. By crafting and implementing supportive policies, strengthening agricultural infrastructure, promoting research and development, facilitating market access, and fostering collaboration, policymakers can guide Nigeria towards a future where food production takes precedence over tobacco cultivation, fostering a healthier, more sustainable, and resilient agricultural sector.