The efforts by world leaders – or lack thereof – has left us with only a 60% chance of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5ºC by 2050. A chance that the African countries and Small Island Developing States cannot afford to take. Their unfavourable positioning in the climate crisis will cause a continuation of escalating sovereign debt and climate-induced loss and damage, and as a consequence vulnerable communities will pay the highest price.

The goal of COP26 was clear: the summit was meant to achieve a deal to provide a fighting chance to avert the worst impacts of climate change. While, initially stronger commitments were tabled, it was significantly watered down to reflect contentious wording on the fossil fuel sector and weak agreements on financial support to poor and vulnerable nations. The lack of adequate action has left the majority of people dissatisfied.

Global climate action since the Paris Agreement in 2015 has been disappointing. As the UN Secretary General, António Guterres, noted in his opening speech at the COP26, the last published report on Nationally Determined Contributions (commitments by each country to reduce carbon emissions, NDCs) shows that current commitments by the parties still condemned the world to a calamitous 2.7 ºC increase.

COP26 delivered new climate change mitigation commitments (such as the Glasgow Climate Pact, Pledge to End Deforestation by 2030, The Global Methane Pledge, and the Pledge to Phase out Coal) and financing pledges ($130 Trillion Global Finance Pledge, $10.5 Billion Fund for Emerging Economies, and $1.7 Billion to Indigenous Peoples). Yet, the outcomes have been grounded with the same narrative that has failed to yield any tangible results to date: a narrative that is rooted in economic imperatives and not equality.

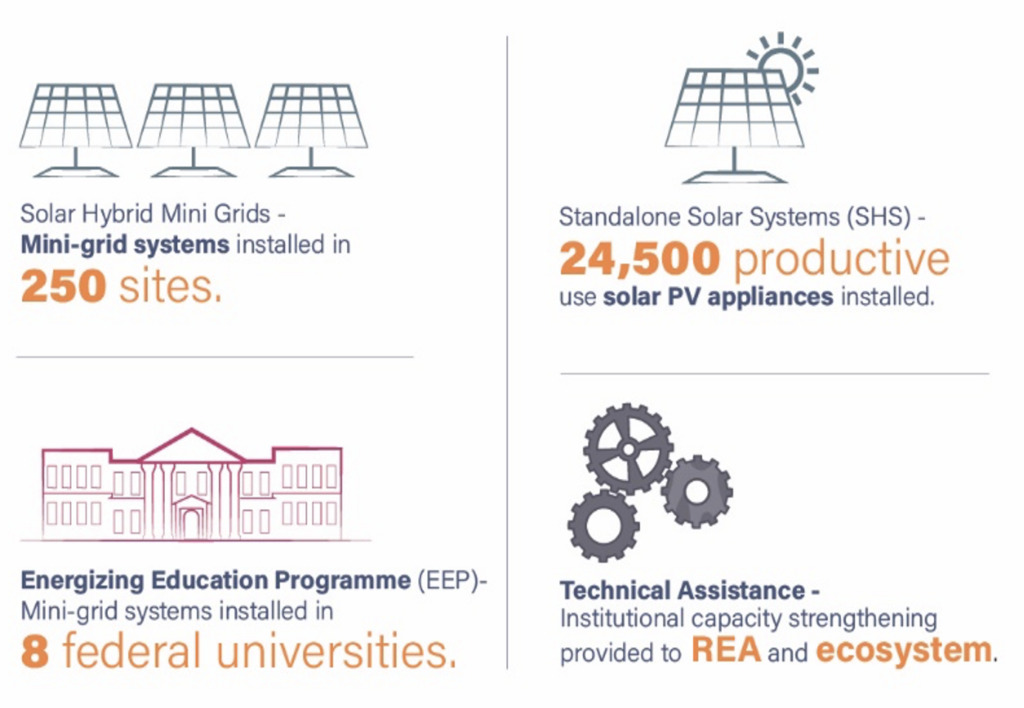

The Nigerian Electrification Project (NEP) is a federal government scheme designed in 2018 with the World Bank, the African Development Bank (AfDB), and other partners to provide energy access to under- and unserved communities in Nigeria using renewable sources. It is a private sector-driven nationwide initiative implemented by the country’s Rural Electrification Agency (REA). The Project promotes electricity access for households, micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), and public education institutions. It specifically aims to provide cost-effective power to 250,000 MSMEs and 1 million households through off-grid and mini-grid systems by 2023 via four main components:1

Read more- Energy for Growth Hub

How can policymakers spur communal investment in education when benefits are shared among all, regardless of contributions? A case study of the Igbajo community in Nigeria’s Osun State finds an answer in the strength of communal ties.

Empirical evidence has highlighted that community involvement can play a key role in expanding access to, and the quality of, education. From the maintenance of better and safer schooling facilities to the creation of more responsive school governance, there is broad agreement that when parents and the broader community are involved in the operation of local schools, higher standards are kept. Yet like most voluntary activities and public goods provision, mobilising and aggregating at times disparate community members’ interests and priorities faces the typical free-rider problem – that is, an inefficient distribution of goods resulting from individuals being able to access the good without paying their share of the costs. Given that the benefits of education are shared irrespective of contribution, investment – of time and money – is often undersupplied. However, this challenge can be surmountable: this blog highlights a case study of community-driven efforts to improve education, drawing conclusions on the replicability of similar cases elsewhere.

The economic literature tends to suggest solutions to free-rider problems that involve some contractual or statutory commitments. For instance, tax laws are designed to overcome free-riding in the provision of public goods and ensure that all – at least in theory – pay their fair share. Similarly, when it comes to the private provision of public goods, proposed solutions often involve the agreement of contracts that make contribution to the common good a Nash equilibrium in a theoretical game-like scenario.

There is, however, a different form of commitment that, when leveraged correctly, can help overcome issues associated with free-riding at a communal level. Sociological literature from the Durkheimian school has long emphasised the importance of group inclusion to individuals. Commitments to the well-being of the community through appeals to ‘groupish' identity and pride can hence be powerful tools to be leveraged in the struggle to generate high levels of community involvement in local education.

In this regard, the example of the Igbajo community in Nigeria’s Osun State can provide an important instructive case study about the potential of communal ties to facilitate the overcoming of free-riding and choice aggregation problems in education.

The town of Igbajo made history in 2009 with the establishment of the first community institution for tertiary education in Nigeria. The high costs and challenging logistics of facilitating a post-secondary institution are enormous in Nigeria, such that only the government and large-scale for-profit private sector investment are considered viable sources for tertiary education funding. This has restricted community involvement in education to primary and secondary education and, at most, to often-ineffective attempts at lobbying for post-secondary education. While, of course, the story of Igbajo includes elements of a paradigmatic tale of local pride and parochialism, it would be hard to put it all down to a natural sense of community pride among Igbajo residents. After all, there is nothing that obviously confines such a quality to any community. Naturally, local pride is expected everywhere.

The reasons why local pride resulted in tangible action can be gleaned in conversation with the key community members behind the project. It was not just pride that guided their decisions – it was a multiplicity of factors that explained the process investing massively in such a project.

First, external factors such as low government support helped generate a sense of being slighted that led to the aggregation of individual interests around a single priority. The community had, in the past, lobbied for the creation of a tertiary school and a local government secretariat as well as for other socio-economic amenities, losing out each time to competing communities. The perceived external threat of neglect creates strong internal cohesion and coordination and adds an elements of urgency to community intervention. This, therefore, can serve as a non-economic incentive to coordinate (or subordinate) individual choices to the collective good.

Moreover, the community has a deliberative system of decision making which proved useful in coordinating individual actors. Through existing social networks within the community, like the Igbajo Social Circle and Igbajo Development Association down to annual kindred meetings, the system of frequent communal interaction makes it logistically simpler for coherent community-level positions to emerge, and, crucially, also serves as a form of peer pressure that encourages active participation and lower tendency to free ride. Further still, the deliberative setting engenders a mechanism for civic responsibility and open recognition of especially-active ‘champions’. This, in turn, creates incentive for individuals to seek the recognition of their peers by taking on larger roles that help drive the initiative. Again, this form of incentive would not have emerged without clear mechanisms of community-level interaction (and pressure).

Indeed, examples like that of Igbajo provide the anecdotal empirical support that underpin the objectives of the RISE Nigeria project. By organising deliberative Education Summits, engaging local populations, and disseminating results widely, RISE aims to test whether institutionalising forms of community involvement and facilitating knowledge generation and dissemination can be useful in sparking forms of community pride and inter-community ‘positive competition’. Does bringing communities together and providing them with information about how they compare to other neighbouring groups create enough social pressure to encourage unselfish behaviour? Can we use informative and deliberative institutions to leverage a Durkheimian collective identity and overcome free riding in education at the community level?

These are important questions that RISE Nigeria seeks to clarify through the lens of political economy experiments. Evidence from this would have important implications for development practitioners around the world. Given the potential of community involvement to spur education, and the obvious implications that might have on broader socioeconomic development, understanding how the interactions work and how the institutional structure can strengthen inter-communal bonds could lay the groundwork for important progress in galvanizing more community engagements in education.

This article was first published on RiSE

Ever wondered why some countries win medals while others do not? Neither do they have the ability to win medals if they participate in sports event such as the Olympics? In developing countries, there are a number of economic concerns regarding sports. Arguments are made that a country’s performance in sports (Olympics) is relative to its economic resources, and that achievements in sport should be measured in terms of a country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita and investment in sport.

A well-organized sport development structure and a high level of funding can propel a country to the top of the medal table. Population is likewise salient, and with 1.4 billion people, China was well represented at the 2020 Olympic medal table, with a total of 88 medals won, trailing only the United States of America which had 113 medals won, a country with more than 300 million people.

Stylized facts on Sport and Economic Development

The three strongest markers of sports development in any economy are the degree of investment, the extent of population participation, and the level of political stability that exists. High investment correlates positively with buoyant economy, which has a knock-on effect on the amount of leisure time utilized. With more leisure hours, a larger proportion of the population can indulge in sports. Developed economies make significant investments in sport facilities, coaching skills, and sports science support programs, all of which are essential for sport sustainability. Sport investment can be an effective stimulus for developing the quality and quantity of sporting activities especially at the international level.

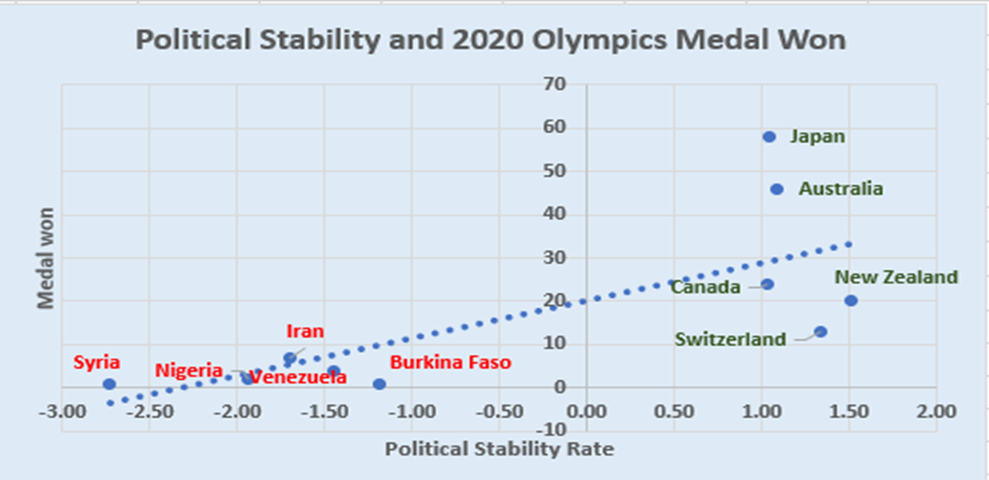

Figure 1 shows a positive correlation existing between political stability and the 2020 Olympic medal table. There is a clear disparity in the number of medals won between countries with stable political systems and those battling political instability.

Figure 1: Political Stability and 2020 Olympics Medal Won

Source: World Governance Indicators 2020 & International Olympic Committee 2021

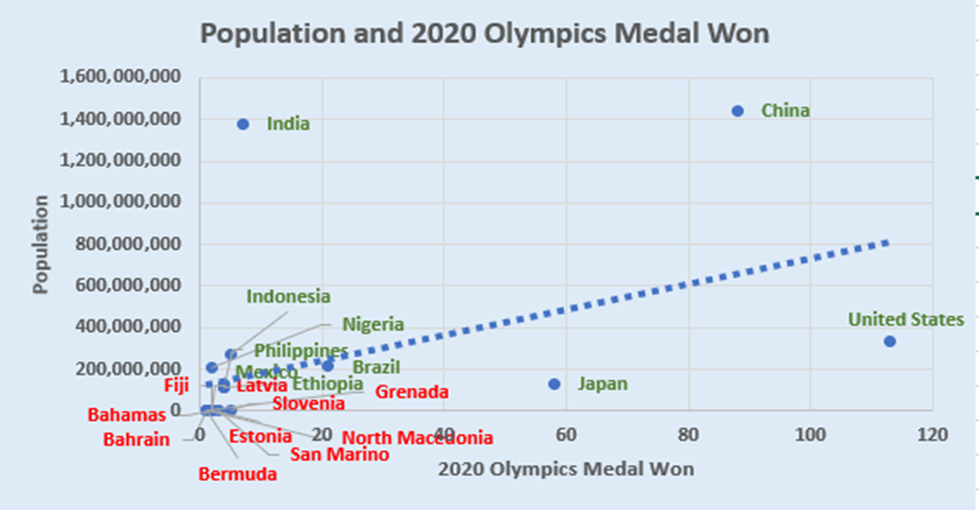

Figure 2: Population and 2020 Olympics Medal Won

Source: Worldometers 2021 & International Olympic Committee 2021

Figure 2 also shows that population matter for the number of medals won. However, we note that this is secondary, as countries like New Zealand and Australia do well in the Olympics despite their relatively smaller population. Large population size, on the other hand, is not a sufficient prerequisite for sport development. Figure 2 however supports the hypothesis that the larger the population, the more athletes with different physical qualities and skills.

Another notable factor is investment, investment in sport clearly plays an important role in some athletic activities than in others. Games like rowing, cycling, golf, shooting, sailing and equestrian require exclusive equipment and amenities; Nigeria have never won medals at any of these sports. Even in less expensive sports, there is a huge inequality in access to coaching and training facilities. A survey in developing countries by UNESCO in 1995, referred to in Manzenreiter (2007), found that 16 of the least developed countries had an average of just 71 football pitches, 31 volleyball courts, 13 athletics tracks and 3 swimming pools per country. In recent times, the African continent has in total, 141 constructed Soccer stadiums and about 78 volleyball courts. The combination effect of investment in sport and human capital, political stability, and high population participation rate are necessary and sufficient for sport development.

Nigeria and Olympics

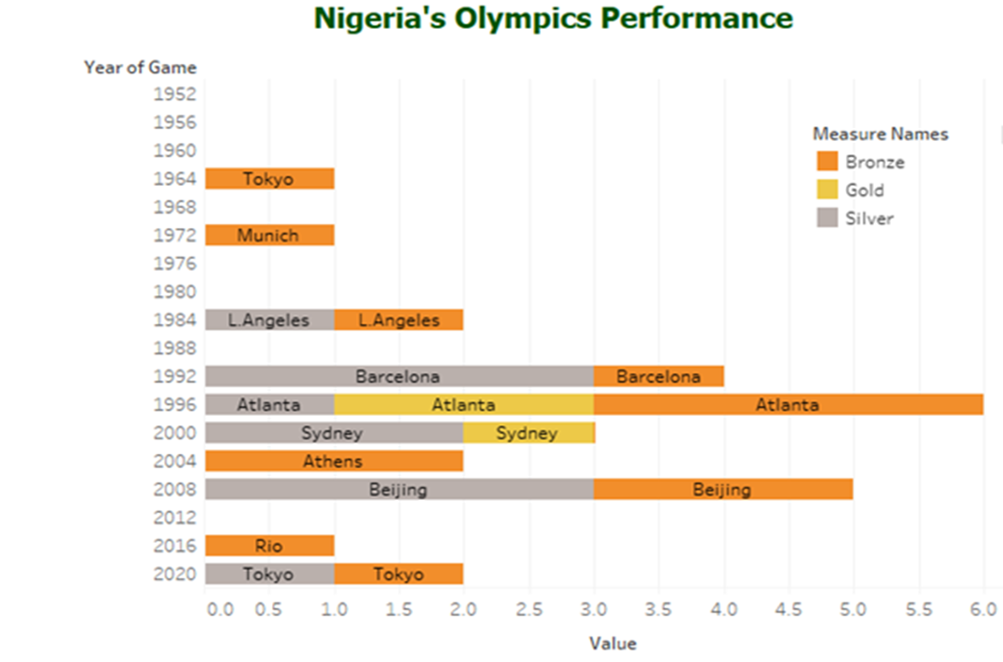

Nigeria officially competed in the Olympic Games in Helsinki 1952 and has since sent representatives to every Summer Olympic Games, apart from the 1976 Summer Olympics, which was boycotted. Nigeria has won 27 Olympic medals in total, including 3 gold, 10 silver and 14 bronze. The majority of the medals come in athletics and boxing. Nigeria achieved her finest result to date in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, when the Dream Team football team were decorated with gold and Chioma Ajunwa won gold in the athletics division. Nigeria’s second best performance was in the 2008 Beijing Olympics where the men’s football team won a silver medal and Blessing Okagbare, an athlete won a silver medal.

Figure 3: Nigeria’s Olympics Performance

Since then, Nigeria's games have been on a downhill spiral. Lamentably, neither the men's nor women's football teams qualified for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, which was compounded by the disqualification of ten athletes.

Socio-economic benefits of Sport

Sports impact on the Nigerian economy may be evaluated in terms of its contribution to GDP, employment, and the indirect multiplier effect on improving public health, reducing crime rates, and supporting other sectors.

Sport is now a significant aspect of vast entrepreneurial activities, providing on the one hand, job creation for many in the various components of sport, and on the other hand, income and revenues to individuals and governments respectively. Currently, assessing the impact of sport on Nigeria's GDP is challenging because sport is not one of the key sectors considered by statisticians when estimating GDP. However, the sector is computed as part of the entertainment and recreation sector, which contributed 0.19, 0.31, and 0.33 percent to the Nigerian GDP in 2019, 2020, and 2021 respectively. Sport contribution remains below one percent due to inadequate finance and investment.

Sport also helps to improve fundamental social and interpersonal skills, which aids in crime reduction and building national unity. Football tournaments, for instance, are regarded as one of the few events in Nigeria that have fostered a sense of national cohesion among the country’s heterogeneous population. In addition, sport provides an important platform for youths to develop life skills that will enable them to cope better with everyday life challenges and transition away from drug abuse, violence, and crime. Sport can be utilized as a medium to advocate for sustainable human rights, such as the right to social security and equality across gender and race.

Strategies to support sport development in Nigeria

Clearly, finance is the major constraint to sport development in Nigeria. There is a need to support national sporting bodies to implement targeted fund-raising programs and prioritize the allocation of resources for sport.

Furthermore, the Nigerian government should strive to implement a comprehensive sports policy that includes encouraging participation in all sporting activities in primary, secondary, and tertiary educational institutions as well as promoting local sports development. There is a need to boost private investors' confidence in the industry so they can fully participate in the business aspect of sports. These will help make the sports sector more appealing for the youth to pursue as a career and profitable for businesses.

With the explosion in digital technologies and data, countries across are grappling with effective ways to address the threats emerging in the digital space as well as provide supportive structure for digital technologies uptake. At present, at least 66 percent of countries in the world has at least a form of data protection laws. By data governance, we mean the processes and laws available in managing the availability, usability, integrity, and security of the data in the digital economy. African continent is not left out in the emerging structure with also proliferation of data governance and policies. However, UNCTAD report in 2020 noted that African region has the lowest adoption rate of the new technology and data protection laws.

CSEA has collected vast dataset to dive deep into the scope and coverage of digital development and evolution of data governance principles in Africa. This is under our project - Strengthening Data Governance in Africa. The Digital Governance Index was designed to evaluate Africa's level of digital development. The Index covers 54 African economies and is derived utilizing 21 dimensions to assess performance across three indicators

We performed detailed analytics (click here) on cross-country performance in these indicators.

The index is expected to be an indicator for assessing African’s digital evolution and uptake. This will help to pinpoint early and late adopters of the digital space as well as their pace. With awareness of the Digital Governance Index, governments and key stakeholders can adapt and integrate policy initiatives to strengthen requisite skills, provide efficient and inclusive digital services to all; bridge digital divides to order to fulfill the principle of leaving nothing behind while fostering economic development. Digital Governance Index will provide policymakers at national and regional level with information to support decision on digitalization policies.