In the Meeting of Goals

How SDG 4 (Quality Education) Intersects with other Sustainable Development Goals in Nigeria.

Let us imagine the pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals metaphorically as a steeplechase – an obstacle-course if you will. Each of the 17 Goals is a different obstacle – a unique hurdle to cross before the race ends at the designated Year 2030 mark. This is a different type of race however – where the objective is not for one winner to emerge, but rather for every participant to clear every obstacle and make it to the end in time. Nonetheless, as it stands, Nigeria along with most of sub-Saharan Africa brings up the rear by a long margin. The Nigerian runner is bereft of shoes (symbolic of marked infrastructure-deficiencies), and is slowed even more by excessive weight (corruption and poor policy-implementation); and he is struggling to keep up. While the front-runners are well on their way, our runner – let’s call him Participant Nigeria – is in such bad shape that he is yet to gain significant traction on any single hurdle. He is challenged severely in the face of each one of them – Gender Equality, No Poverty, Clean Water and Sanitation, and the other 14. Participant Nigeria can use all the help he can get to finish this race, but his task is daunting – with each obstacle apparently more imposing than the next, the prospect of surmounting the collective in time is Herculean at best. For all the runners, and more so for the ones trailing behind, it would pay to approach the race holistically. It would help to recognize the race as more than merely a sum of disjointed barriers; but that rather, in streamlining effort, leverage is possible between the one barrier and the next. For instance, if the peak of two obstacle stand close by at similar heights, then instead of climbing the second obstacle from the bottom, a runner would simply cross the one peak to the other. This is synergy.

– Gender Equality, No Poverty, Clean Water and Sanitation, and the other 14. Participant Nigeria can use all the help he can get to finish this race, but his task is daunting – with each obstacle apparently more imposing than the next, the prospect of surmounting the collective in time is Herculean at best. For all the runners, and more so for the ones trailing behind, it would pay to approach the race holistically. It would help to recognize the race as more than merely a sum of disjointed barriers; but that rather, in streamlining effort, leverage is possible between the one barrier and the next. For instance, if the peak of two obstacle stand close by at similar heights, then instead of climbing the second obstacle from the bottom, a runner would simply cross the one peak to the other. This is synergy.

However, progress in one area can sometimes amount to regress in another, in this race. Sometimes obstacles are not situated close to one another, but are instead far apart and in opposite directions. In this unique, non-linear race, where two obstacles are thusly divergent, the runner in advancing towards one would be moving further away from the other. It is therefore often a toss-up, where the runner has to make the choice for that time of which obstacle to move toward, and by so doing, which obstacle he would be moving away from.

However, progress in one area can sometimes amount to regress in another, in this race. Sometimes obstacles are not situated close to one another, but are instead far apart and in opposite directions. In this unique, non-linear race, where two obstacles are thusly divergent, the runner in advancing towards one would be moving further away from the other. It is therefore often a toss-up, where the runner has to make the choice for that time of which obstacle to move toward, and by so doing, which obstacle he would be moving away from.

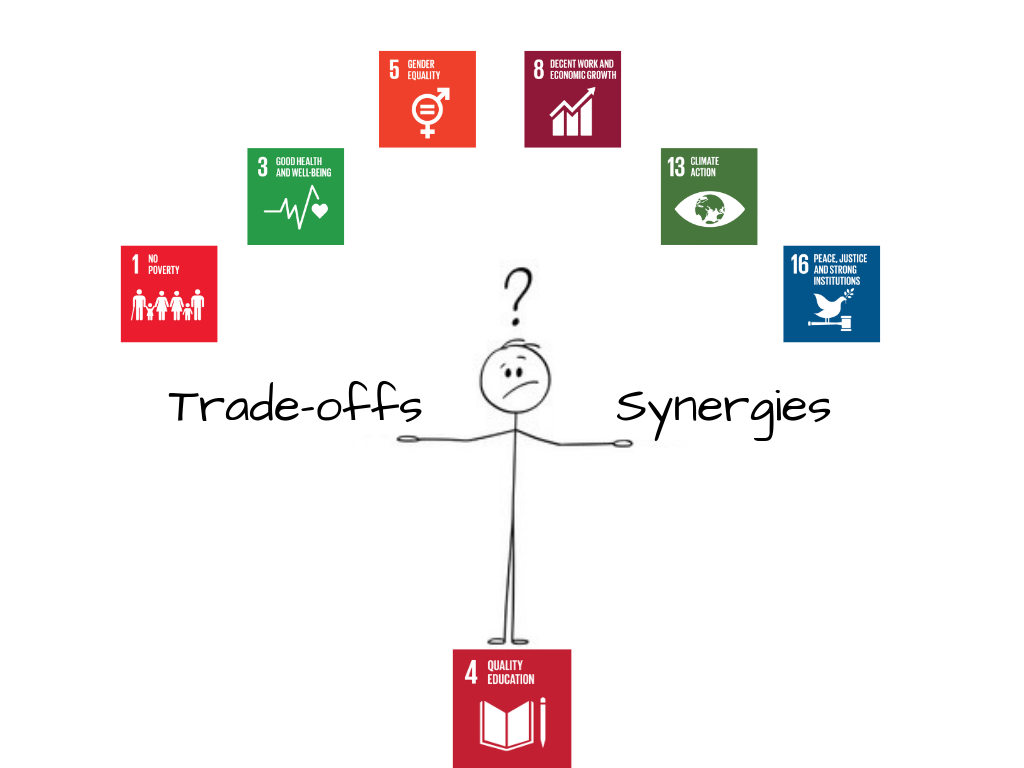

These are trade-offs, and they are just as significant as synergies. In the real sense, this is how synergies and trade-offs between Sustainable Development Goals work.

These are trade-offs, and they are just as significant as synergies. In the real sense, this is how synergies and trade-offs between Sustainable Development Goals work.

The agenda of the Sustainable Development Goals is for no one to be left behind in the pursuit and attainment of wellbeing and prosperity globally by the year 2030. The Goals are integrated in their design, and this means that in recognizing that efforts in one area might impact those in another, a concerted balance is built throughout the Goals, in the design of targets across economic, social and environmental fronts. Contexts in different geographical regions and cultures however differ, and integration between Goals is not always immediately attainable. For instance, road construction through the Amazon Forests in Brazil while aligning wholly with SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), driving SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and complementing SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth); amounts to a massive trade-off with SDG 13 (Climate Action), in the diminishing of the Amazon Forests (the Forests are the “Lungs of the Planet” that produce 20% of the oxygen in its atmosphere, and a reduction in their size bodes ill for the Earth’s climate). In translating the Goals to specific environments therefore – in building policy and planning implementation around them – the determination of potential trade-offs and synergies between them is critical.

The fourth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 4) – Quality Education – places significant focus on Least Developed Countries (LDCs), where poverty stretches the gaps in development and in learning outcomes. Nigeria is currently not on track to achieving SDG 4 – it has the highest number of out-of-school children globally, as well as very low output-levels in quality of education. In a study to ascertain the drivers to exclusion from quality education in Nigeria by the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa, a tier of the assessment was a cross-referencing of SDG 4 with other Sustainable Development Goals to identify synergies and trade-offs. While education is integral to development on a whole, specific interactions were identified between SDG 4 and SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), in the following ways:

SDG 1 (NO POVERTY)

The correlation was adjudged strong, where high levels of achievement in education expand access to meaningful livelihood opportunities, and thereby forestall poverty. Inversely, greater incomes enable better access to quality education.

SDG 3 (GOOD HEALTH AND WELL-BEING)

SDG 4 reinforces SDG 3, in that higher levels of attainment in education mean higher knowledge-levels for mothers regarding healthcare for their young; and infant mortality rates are lower as an outcome.

SDG 5 (GENDER EQUALITY)

Education is an imperative, if women are to understand and assert their rights, and assume full roles in society. Education is also necessary to the larger society in its appreciation of the place of the female within it.

SDG 8 (DECENT WORK AND ECONOMIC GROWTH)

Education drives entrepreneurship and economic activity on an individual level, and market competition and growth on the collective one.

SDG 13 (CLIMATE ACTION)

Quality education allows an understanding of the threats posed by our changing climate, and of what actions might mitigate them.

SDG 16 (PEACE, JUSTICE AND STRONG INSTITUTIONS)

Education engenders tolerance and civility, to build more cohesive and peaceful societies by.

The good news is that there were no trade-offs identified in the study. A broad implication of the productive interactions thus identified between SDG 4 and other Goals is that quality education is entirely beneficial to sustainable development in-country. If we are to cover ground in the SDG race, especially given Nigeria’s poor performance so far regarding Quality Education and other areas, a holistic approach toward policy design and implementation around the Goals is necessary, to direct outcomes towards what is intended in both the driving impact of education, and in the advancement of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda on a whole; so we are not left behind.

GO FURTHER…...read the full CSEA paper Is Nigeria on Track to Achieving Quality Education for All? Drivers and Implications

GO FURTHER…...read the full CSEA paper Is Nigeria on Track to Achieving Quality Education for All? Drivers and Implications

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China

In 2017, the average pack of cigarettes cost N183.50 in Nigeria. Excise tax is charged at only 20% ad valorem on Unit Cost of Production (UCA). Furthermore, imported cigarettes are excluded from excise tax; they are rather charged a 40% of CIF import levy, along with other smaller levies. A general Value Added Tax of 5% is applicable to both imported and domestically produced cigarettes. In the end, retail values of cigarettes in Nigeria are comparatively low.

In 2017, the average pack of cigarettes cost N183.50 in Nigeria. Excise tax is charged at only 20% ad valorem on Unit Cost of Production (UCA). Furthermore, imported cigarettes are excluded from excise tax; they are rather charged a 40% of CIF import levy, along with other smaller levies. A general Value Added Tax of 5% is applicable to both imported and domestically produced cigarettes. In the end, retail values of cigarettes in Nigeria are comparatively low. The simulations showed that meaningful upward reviews of excise tax level on cigarette alongside a change to the specific tax system yield the most significant gains in public health (measured by increase in excise tax and other government revenues). The most favorable outcomes in magnitude and direction were recorded in the policy intervention simulations that substantially raised excise tax levels and applied the specific tax system.

The simulations showed that meaningful upward reviews of excise tax level on cigarette alongside a change to the specific tax system yield the most significant gains in public health (measured by increase in excise tax and other government revenues). The most favorable outcomes in magnitude and direction were recorded in the policy intervention simulations that substantially raised excise tax levels and applied the specific tax system.

It used to be that in Nigeria, a baby’s first words would almost certainly be ‘mommy’……..or ‘dada’ in the very least. Now, you’re lucky if the first thing your infant ever says isn’t ‘Up NEPA!’. That is how much worse the electrical power situation has become from, say, when baby-boomers were children. Nigerian millennials have been born into a reality where uninterrupted electrical power is the exclusive preserve of the filthy rich – and basically unheard of otherwise.

This sustained electrical power-supply quandary derives from a characteristic lack in both infrastructure management and policy enforcement; both situations inherent to a culture of deficient political will in matters of public welfare – in a county that has struggled unsuccessfully for decades to find a balance in governance. The Nigerian government held absolute monopoly of power generation, transmission and distribution from the very start, you see. The numbers have been abysmal – even though Nigeria has utilized electricity for over a century, in the nineties about half of a population of well over a hundred million had no access to it. In the noughties (in 2009), the country was rated by the World Bank as operating the most inefficient electrification system globally. In spite of its vast superiority in human population figures to a host of other African countries, Nigeria generates far less electrical power than they do; and has consistently fallen well short of accommodating the demands of a rapidly and continually expanding population.

It used to be that in Nigeria, a baby’s first words would almost certainly be ‘mommy’……..or ‘dada’ in the very least. Now, you’re lucky if the first thing your infant ever says isn’t ‘Up NEPA!’. That is how much worse the electrical power situation has become from, say, when baby-boomers were children. Nigerian millennials have been born into a reality where uninterrupted electrical power is the exclusive preserve of the filthy rich – and basically unheard of otherwise.

This sustained electrical power-supply quandary derives from a characteristic lack in both infrastructure management and policy enforcement; both situations inherent to a culture of deficient political will in matters of public welfare – in a county that has struggled unsuccessfully for decades to find a balance in governance. The Nigerian government held absolute monopoly of power generation, transmission and distribution from the very start, you see. The numbers have been abysmal – even though Nigeria has utilized electricity for over a century, in the nineties about half of a population of well over a hundred million had no access to it. In the noughties (in 2009), the country was rated by the World Bank as operating the most inefficient electrification system globally. In spite of its vast superiority in human population figures to a host of other African countries, Nigeria generates far less electrical power than they do; and has consistently fallen well short of accommodating the demands of a rapidly and continually expanding population.

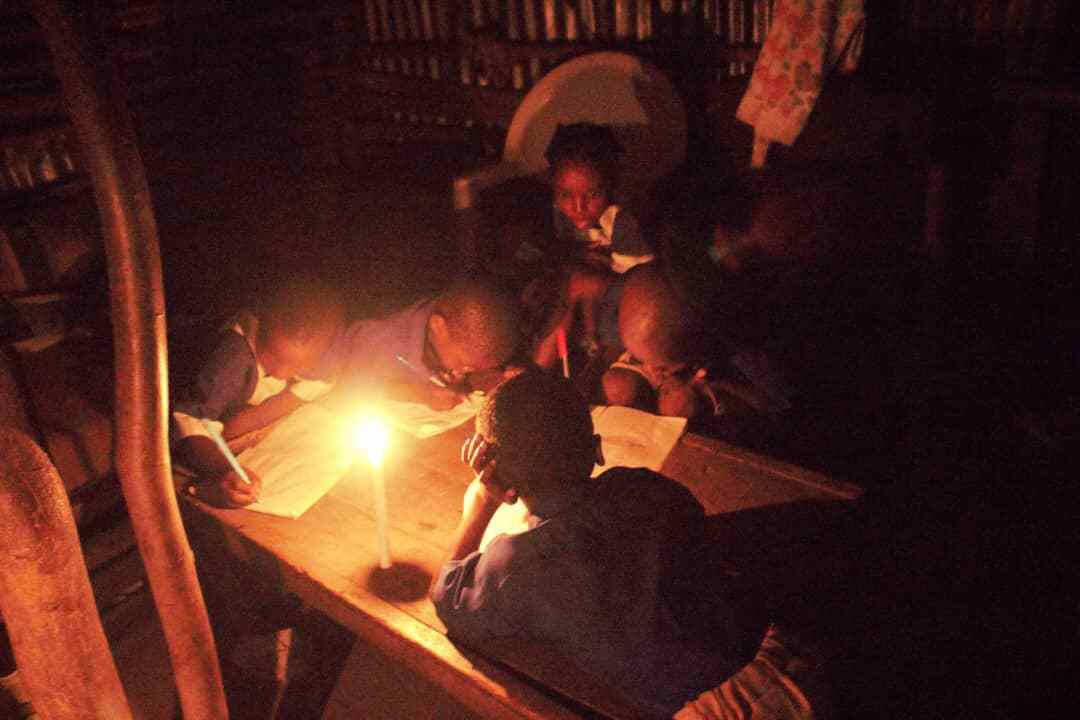

A SADLY COMMON SCENE IN NIGERIA – CHILDREN DOING HOMEWORK BY CANDLELIGHT

IN LAGOS (IMAGE FROM newdiplomatng.com)

Furthermore, the local power industry has traditionally bled huge commercial and collection losses – in 2009 for instance it was estimated that only about 50% of power used was paid for by consumers.

A SADLY COMMON SCENE IN NIGERIA – CHILDREN DOING HOMEWORK BY CANDLELIGHT

IN LAGOS (IMAGE FROM newdiplomatng.com)

Furthermore, the local power industry has traditionally bled huge commercial and collection losses – in 2009 for instance it was estimated that only about 50% of power used was paid for by consumers.

With democracy emerging after numerous years of high-handed military rule, the notion was engaged to open up the electricity generation, transmission and distribution processes to private-sector participation; to chase down much needed improvements in those areas.

With democracy emerging after numerous years of high-handed military rule, the notion was engaged to open up the electricity generation, transmission and distribution processes to private-sector participation; to chase down much needed improvements in those areas.  PRICING AND ALLOCATION REFORM FOR NATURAL GAS

Seeing as about 80% percent of electricity generation is from natural gas, it follows then that revising regulatory frameworks regarding gas transmission and distribution operations, as well pricing; in what manner to optimally streamline those processes is imperative.

REGULATING THE MARKET

Challenges encountered beyond the privatization of the electricity sector provide ample insight for fashioning built-to-fit regulation of current market operations; channeling effort for maximum yield.

RESTRUCTURING PRICING AND TARIFF

The unsustainable low-pricing model for electricity retail, at the expense of profit, diminishes the investment-appeal of industry operators; stumping the market consequently. An appropriate pricing structure would realistically factor running costs, and thus render generation and distribution companies more viable.

MINI-GRIDS

Off-grid and mini-grid initiatives and regulations are timely and essential – to attract investors discouraged by stringent participation-stipulations around the national grid; as well as to service remote locations inaccessible to it.

ALLAYING CONCERNS REGARDING PAYMENT RISK

Government institutions within the sector will have to project greater reliability by differentiating between legitimate potential-investor demands and unwarranted requests for government guarantees and undertakings; as well as assure equitable risk-sharing across the entire value chain.

COMPLETE TRANSPARENCY IN PROJECT DEVELOPMENT, PROCUREMENT AND CONTRACTING

Public-funding will be offered more readily when transactions are conducted with the utmost transparency and integrity.

FINANCING

Facilities sourced from local institutions are unfeasibly expensive, when available. Necessary intervention to improving access to finance will boost investment. Alternative investment avenues, such as pension funds, also fit nicely into the longevity of amortization of investment characteristic of the electrical power sector.

CONSUMER CONSCIENTIOUSNESS

Consumer best practices such as energy conservation and timely payment of charges, as well as ceasing power theft and infrastructure vandalism all translate to more available electricity overall.

In the end, the phrase ‘Up PHCN!’ (regardless of the popularity still of the old one, the moniker is indeed different now) should hold new meaning – it should become an expression of appreciation for consistency, rather than of thankfulness for brief respite after prolonged darkness.

…..And there was light!

GO FURTHER……read the full CSEA paper

PRICING AND ALLOCATION REFORM FOR NATURAL GAS

Seeing as about 80% percent of electricity generation is from natural gas, it follows then that revising regulatory frameworks regarding gas transmission and distribution operations, as well pricing; in what manner to optimally streamline those processes is imperative.

REGULATING THE MARKET

Challenges encountered beyond the privatization of the electricity sector provide ample insight for fashioning built-to-fit regulation of current market operations; channeling effort for maximum yield.

RESTRUCTURING PRICING AND TARIFF

The unsustainable low-pricing model for electricity retail, at the expense of profit, diminishes the investment-appeal of industry operators; stumping the market consequently. An appropriate pricing structure would realistically factor running costs, and thus render generation and distribution companies more viable.

MINI-GRIDS

Off-grid and mini-grid initiatives and regulations are timely and essential – to attract investors discouraged by stringent participation-stipulations around the national grid; as well as to service remote locations inaccessible to it.

ALLAYING CONCERNS REGARDING PAYMENT RISK

Government institutions within the sector will have to project greater reliability by differentiating between legitimate potential-investor demands and unwarranted requests for government guarantees and undertakings; as well as assure equitable risk-sharing across the entire value chain.

COMPLETE TRANSPARENCY IN PROJECT DEVELOPMENT, PROCUREMENT AND CONTRACTING

Public-funding will be offered more readily when transactions are conducted with the utmost transparency and integrity.

FINANCING

Facilities sourced from local institutions are unfeasibly expensive, when available. Necessary intervention to improving access to finance will boost investment. Alternative investment avenues, such as pension funds, also fit nicely into the longevity of amortization of investment characteristic of the electrical power sector.

CONSUMER CONSCIENTIOUSNESS

Consumer best practices such as energy conservation and timely payment of charges, as well as ceasing power theft and infrastructure vandalism all translate to more available electricity overall.

In the end, the phrase ‘Up PHCN!’ (regardless of the popularity still of the old one, the moniker is indeed different now) should hold new meaning – it should become an expression of appreciation for consistency, rather than of thankfulness for brief respite after prolonged darkness.

…..And there was light!

GO FURTHER……read the full CSEA paper