Why Digitalization and Digital Governance Are Key to Regional Integration in Africa

On January 1, 2021, the long-anticipated African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) became a reality. The benefits of creating a single African market under the AfCFTA are wide-ranging and potentially revolutionary. By reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers to intra-African trade, the initiative could boost regional exports by 29 percent and income by 7 percent between 2020 and 2035. There is also optimism that greater access to a larger market base could reduce production costs and lead to greater economies of scale for local producers and exporters.

But AfCFTA’s potential might not be fully realized without stronger digital connectivity and effective policies that (1) promote the free flow of data and information across member states to facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration and (2) reduce trade integration costs and address existing structural barriers to intra-regional trade in Africa.

How digitalization can help to address structural barriers to trade in Africa

At the most basic level, AfCFTA is governed by five operational instruments (an online negotiating forum; a digital payment system; the monitoring and elimination of non-tariff barriers; the African Trade Observatory (ATO); and rules of origin), all of which require effective digital connectivity to be successful. More importantly, developing the continent’s digital sector is crucial for economic integration and could help address some long-standing structural trade barriers while ensuring that the gains arising from the AfCFTA are equitably shared. Examples of how strengthening the digital economy can break down these barriers include:

- Digitalization ensures optimal trade and business processes resulting in cost reduction. The use of digital technologies can reduce transaction costs such as search costs, language barriers, and coordination of logistics that are associated with traditional delivery channels. Greater adoption of digitalization in customs’ management and procedures can also improve regulatory inefficiencies to speed up transit and clearance of exports; this could reduce additional export costs like demurrage charges to suppliers. As the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic indicates, business adaption and resilience to shocks are more enhanced with access to digital platforms.

- Faster and easier information flow for improved participation in the global supply chain: Digital platforms have proven particularly useful in connecting potential buyers and sellers in multiple jurisdictions and eliminating burdensome processes in the value chain. Digitally sharing information about regulations and standards among market actors, and allowing better knowledge of consumer preferences, increases access to trade opportunities. Greater availability of market intelligence through big data analysis can make it easier for African suppliers to increase their participation in global value chains beyond just providing raw materials and inputs.

- Greater access to markets, especially for small enterprises which make up the vast majority of firms in most countries:In Nigeria, for example, 95 percent of firms fall into the category of micro and small enterprises. These businesses generally have less capacity in terms of financing options and digital skills to adapt their business operations to compete in the regional and global markets. Indeed, in Nigeria only 18 percent of micro and small enterprises are even aware of AfCFTA, compared to 67 percent of medium-scale enterprises. Digital technologies can increase the economic access of the disadvantaged groups, including those operating in the informal sector and in rural areas by removing barriers to business expansion while promoting the development of more efficient services for the continent’s rapidly growing consumer class. In addition, digitalization could promote access to fintech credit facilities, crowdfunding, and other less stringent funding and payment options for small-sized export firms to improve their capacity to expand and serve a larger customer base. E-commerce platforms also provide less costly opportunities to build and accumulate verifiable digital presence and track record which can increase such firms’ ability to attract new domestic and foreign business partners and customers.

Despite the vast potential and importance of digitalization for regional integration, digital development remains low across Africa. The problem is notable in two crucial areas: digital penetration and data governance framework. The capacity to address these challenges will determine the AfCFTA’s success. We briefly highlight the critical issues along these areas.

Digital penetration and preparedness are still very low in Africa

Access to the internet remains limited in Africa, with 47 percent of the continent’s population able to access the internet, compared to a global average of 63 percent. The quality of digital infrastructure is also poor, with slower 2G still accounting for 59 percent of the available mobile technology generation mix and 4G penetration at just 6 percent of the mix. It is therefore unsurprising that most African countries are inadequately prepared to leverage the global digital revolution.

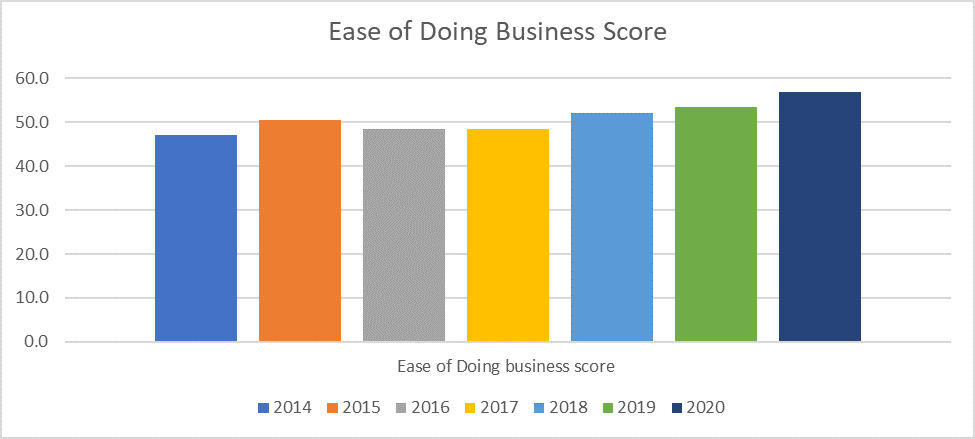

To gauge the implication of this on the AfCFTA, which is expected to be facilitated mainly through online transactions, we measure the correlation between an index of digital preparedness among African countries, and an index measuring the commitment and readiness for AfCFTA. Figure 1 suggests a positive relationship, which implies countries with weaker starting positions on the digital preparedness index are more likely to be left behind as benefits from the AfCFTA accrue to better-prepared countries.

Figure 1. Relationship between Digital Preparedness and Readiness for AfCFTA

Disruptions caused by COVID-19 have already highlighted the importance of better digital connectivity across AfCFTA members. The AfCFTA Phase II negotiations, which were forced online due to the pandemic, were slowed by connectivity problems and concerns about the security of online discussions. Given that governments continue to experience difficulties digitally connecting with one another, small and micro firms and households undoubtedly face more severe challenges.

The absence of national and regional data governance frameworks is a problem

Supporting greater cross-border economic activities on the continent will lead to increased cross-border data sharing. It also requires greater harmonization on how AfCFTA members govern the use of data and digital systems like payments and digital identity, and greater coordination on issues such as taxation of digital platforms and industrial policies aimed at supporting digital entrepreneurs.

Since trust is a prerequisite for ensuring uninterrupted cross-border digital interactions, a clear data governance structure at the national and regional levels is needed. Such laws are required to allay fears related to protection of citizen’s constitutional rights, including the rights to privacy, data protection, and freedom of speech.

There have been some initial steps: At a regional level, the African Union (AU) initiated a Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection in 2014. However, it is still pending ratification, as only eight countries have assented. More recently, the AU, alongside other development partners, developed a digital transformation strategy for the region. The strategy’s objective is to serve as a roadmap in harnessing digital technologies to promote a fully integrated and inclusive digital society by 2030, with the hope that it improves the welfare of Africa’s population. Since the strategy is relatively new, it is premature to assess its effectiveness. Despite these regional action plans and convention, a robust and coordinated regional data governance framework to ensure seamless data interoperability is lacking.

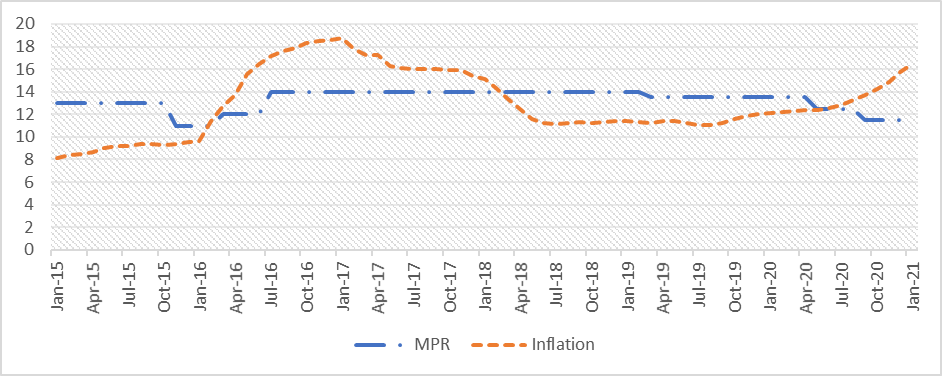

The United Nations Congress on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reports that a significant number of African economies have yet to enact legislation to safeguard digital transactions and data use (figure 2). And due to countries’ varying digital maturity levels, most African countries that have or are drafting data protection laws are adopting different rather than harmonized strategies, risking market fragmentation. Enforcement capacity, financial and human resources, and reliable institutions to support a well-functioning data governance environment are also lacking in most countries.

Figure 2. Number of African countries that have adopted digital protection-related legislation

Source: UNCTAD E-Commerce Legislation Index - April 2020

The way forward

To increase the competitiveness of the African digital economy and maximize the potential of the AfCFTA, governments, non-state actors, and development institutions should collaborate to ensure the speedy implementation and enforcement of data governance policies and laws that guarantee trust, transparency and increase digital inclusiveness.

Beyond ensuring security of data flows, it has become extremely critical to build the soft and hard infrastructure for a well-positioned African digital economy, through expanded access to digital technologies, wider internet adoption, improved public expenditure on information communications technology infrastructure, and a more conducive regulatory environment for private sector investments in the sector. The African Development Bank’s Programme on Infrastructure Development for Africa (PIDA) is one vehicle to achieve this. However, it will require a stronger linkage to AfCFTA for better trade facilitation and a more supportive legal framework. This could be in form of providing guidelines on minimum standards, a shared pool of resources, and a timeframe for effecting harmonized interventions especially for countries that are lagging in growing their digital economy. Further, at the country level, digitalization must become a top development priority for governments, with necessary policy reforms and budgetary allocations to accelerate digitalization and deliver on shared prosperity that the AfCFTA promises.

This article was first published at Centre for Global Development

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China