The COVID-19 pandemic has had a debilitating effect on the Nigerian economy. Specifically, the combination of lockdown measures and the global slowdown of economic activities led to the contraction of Nigeria's GDP by 6.1% in the second quarter of 2020, thus inducing the country's second recession within five years . Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the pandemic occurred amid prevailing economic vulnerabilities.

This policy brief examines the pre-existing economic vulnerabilities, evaluates the Nigerian government's responses to the pandemic with regards to achieving a green and more diversified economy, and develops a new agenda and strategies for sustainable growth and economic transformation.

While the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) provides opportunities for regional financial sector development, it also poses a real test for the continent’s financial system. The ability of Africa’s financial sector to perform the crucial function of facilitating economic growth and integration, at the required scale to support the capacity of small firms to benefit from the single African market remains shaky. In terms of opportunities, the elimination of inhibitive regulations under the AfCFTA is expected to ease cross border trade, enable capital and information flow, attract greater foreign and intra-continental investments, potentially increase capital funds, and provide a much larger customer base for financial institutions to serve. This potential new market base includes traditionally excluded micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) that constitute a large share of the African economy. MSMEs are expected to be a major catalyst for increasing intra African trade and shared economic growth. However, the constraint to MSME financing is a major threat to the success of the AfCFTA as effective economic integration and development depend on easily accessible and affordable capital. This brief therefore advocates for urgent implementation of harmonised financial sector policy reforms across the continent to eliminate these funding constraints, and allow for a more supportive business environment.

Click link below to download full brief

This research analyses the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on micro, small and medium business activities, and its implications for how to be better prepared for possible future socioeconomic shocks, and the geopolitical repercussion for African governments.

This article was first published as a Visiting Scholars’ Opinion Paper for the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy (KIEP)

This brief assesses the policy responses to COVID-19 among low-income countries (LICs) in Africa. While LICs have adopted expansionary fiscal and monetary policies in the face of economic lockdown, as well as other mitigation strategies, the scale and quality of such responses have been modest compared with those of emerging and middle-income countries. Policy instruments have also varied across countries, in line with the level of development of domestic financial markets and the extent of digital inclusion. Pre-pandemic economic challenges, such as limited fiscal space, high debt levels and inflation, have also contributed to countries’ weak economic responses. External financing has been crucial for LICs’ ability to respond to the pandemic, but, is still inadequate given the huge financial gap that exists. As LICs move from the relief to the recovery phase of COVID-19 economic management, a rethinking of economic responses is crucial both to bring about a swift recovery and to minimise the catastrophic impact of COVID-19 on recent developmental gains.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating effect on both developed and developing countries. While the burden of disease and the health implications have been felt most acutely by developed and a few emerging economies, all countries have experienced serious economic consequences. At the peak of the crisis, 161 countries were under some form of lockdown, which put a severe strain on their economic and trade activities. Developed countries used their enormous financial capacity to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic with expansionary fiscal and monetary policies and social palliatives. By April 2020, the US alone had spent over $6 trillion in COVID-19 response measures, while the EU later introduced a $500 billion stimulus package.

Low-income countries (LICs) in Africa, in turn, responded to the health crisis with lockdowns and the heavy curtailment of economic activity. However, the scale and scope of their mitigation strategies paled in comparison with those of most developed countries. The total COVID-19 budget of African countries stood at $37.8 billion in April 2020, with South Africa and Egypt responsible for 84% of that amount. This implies that most LICs lack the financial capacity to respond meaningfully to the pandemic. In addition, prospects of securing external financial assistance are limited, given that every country is facing a similar crisis.

With many countries already reopening their economies and focusing on recovery efforts, important questions need to be asked about the African LIC experience. In the initial phase of the crisis, how did African LICs use the various policy tools at their disposal (fiscal, monetary and exchange rate) to effectively manage the crisis? How did their economic responses evolve – especially compared with their responses to past economic challenges, like the global financial crisis (GFC)? What worked, where did it work and why did it work? Looking ahead, what crucial lessons have LICs learned from economic recovery efforts? This policy brief delves into these important questions.

While public health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have followed a similar pattern of public awareness creation, testing, tracking, therapeutic management of those infected and physical restrictions (lockdowns and shutdowns) to curb its spread, economic responses have varied significantly across countries, given different fiscal space and prepandemic economic fundamentals.

Economic responses have cut across three policy domains: fiscal; monetary and macro-financial; and exchange rate/ balance of payments. Economic responses have also been shifting as the pandemic has progressed. At the onset, the focus of economic policy responses was on delivering relief to vulnerable populations and those in precarious employment whose livelihoods were affected by the lockdowns. Now, with a better understanding of the patterns and effects of the disease, more countries in Africa are moving towards reopening their economies and directing their economic policy responses at recovery, following the initial economic shocks.

Below we briefly enumerate these policy responses among LICs in Africa and compare how these interventions diverge from past responses to economic crises, notably the 2007– 2008 GFC.

Fiscal policy: This includes economy-wide and sectoral interventions using taxation/subsidy, public expenditure and deficit-financing instruments. The first line of intervention in many countries is emergency budget support for the health sector and the scaling up of social protection for vulnerable households in the form of direct cash transfers, a debt moratorium, and financial support for small and mediumsized enterprises and the informal sector. In many cases, expenditure has been reprioritised to focus on immediate needs in the health sector. For countries with less fiscal space, interventions have taken the form of taxation-related measures, such as tax relief and utility bill freezes, among others. There has also been an increase in deficit financing or drawing down savings.

Most LICs in Africa have used one or more forms of the fiscal policy instruments mentioned above. The most common fiscal policy instrument has been budget support for the health sector, through either reprioritisation or an expansionary policy. Only a few LICs have implemented social transfer programmes/support for households or firms. Moreover, the size of countries’ fiscal stimulus has been small, generally ranging from 1% to 2% of gross domestic product (GDP).1The few exceptions among LICs are Senegal, Niger, Mozambique and Namibia, whose fiscal stimulus injections have amounted to more than 4% of GDP. Other limiting factors in terms of fiscal response (which were evident before the pandemic) are the absence of a social register, especially for urban residents who have carried practically the full burden of the lockdown, and low financial and digital inclusion, which has constrained the distribution of support. Despite these constraints, LICs have still managed to introduce several innovative and cost-effective interventions, such as tax relief (Senegal and Madagascar), a utility bill freeze and a waiver of fees for basic services (Niger), and the distribution of food aid (Senegal and Liberia).2

On the revenue side, the pandemic has affected the economic performance of most African countries, with government revenue projected to decline by more than 12% in 2020. Domestic resources thus make a limited contribution to government policy responses. However, early debt forgiveness and credit facilities granted by donors have helped to expand fiscal space in many LICs on the continent.

Monetary and macro-financial policy: Central banks, in a coordinated effort with fiscal authorities, have used expansionary monetary policy, in the form of increased money supply, through traditional, open-market operations as well as quantitative easing. Another tool that central banks are deploying is macro-financial assistance, which comprises medium/long-term loans or grants to businesses or households, as a way of cutting through the commercial banking system. In addition, there are support measures for commercial banks and other financial intermediaries that take the form of extended credit lines, higher liquidity and extensions to collateral frameworks. However, monetary policy interventions face some risks when it comes to managing the trade-off between growth-enhancing policies and inflation. Central banks are also using moral suasion and forward guidance to encourage commitment to specific policy directions in a bid to stabilise the financial system.

Expansionary monetary policy is by far the most common economic response deployed by African LICs.3One reason for its popularity is that the fiscal space in most countries is heavily constrained owing to high debt levels and weak revenue flows. A change in interest rate policy is another widely used instrument. Countries in the Economic Community of Central African States, which have limited control over interest rate policy, mostly rely on injections of liquidity and extended deadlines for the repayment of loan securities held by credit institutions. Nine of the LICs in Africa implement no monetary policies, according to the World Bank.4These are mostly countries whose weak financial markets make the application of monetary policy difficult. In many countries, too, the use and likely effectiveness of monetary policy is influenced by high inflation, which was evident before the pandemic.

Exchange rate/balance of payments policy: The COVID-19 pandemic has affected demand patterns and global supply chains to the extent that they have disrupted foreign exchange earnings for many African LICs. The oil price crash that occurred during the pandemic generated an additional external shock for petro states and worsened foreign reserves. Some countries, like Nigeria, responded to this threat by changing the exchange rate regime or depreciating their currency.5In addition, countries that lost control of inflation owing to their expansionary monetary policies used exchange rate policy as an alternative tool to address inflationary pressures.

Among the LICs in Africa, only Zimbabwe has made an explicit change to its exchange rate policy, by moving from a flexible to a fixed exchange rate in the face of the country’s forex crisis. However, most countries’ monetary authorities are using forward guidance to win support for interventions in forex markets in cases of high volatility or significant currency depreciation. For example, the banks of Uganda, Comoros and Sierra Leone have committed to intervening in the foreign exchange market.6In contrast, Angola, Eswatini and Nigeria (all lower-middle-income countries) have depreciated their currencies in response to COVID-induced economic shocks.

LICs have recorded fewer cases of currency depreciation than the frontier economies in Africa. Overall, the exchange rate policy has not played a major role in LICs’ policy responses in recent months.

Given the inadequate scale of domestic resources among LICs, the second layer of interventions has come in the form of donor support. This includes multilateral support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the African Development Bank (AfDB), as well as bilateral interventions from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries and even countries in the Global South. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA)7has collected detailed data on appeals for funding from developing countries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the total receipts so far.

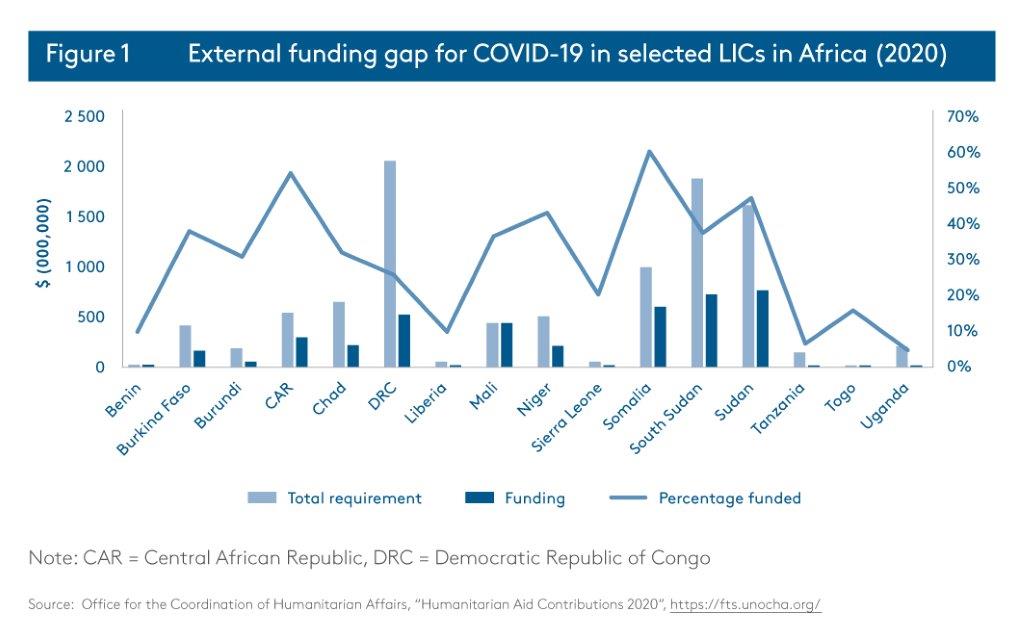

As shown in Figure 1, a financing gap (the difference between need and actual allocation) is observed for all LICs, but it varies across countries. For example, Somalia and the Central African Republic have received 60% and 54%, respectively, of their appeal funds, while Uganda and Tanzania have received only 5% and 7%, respectively. A notable trend is that fragile states receive a higher proportion of the funds for which they have appealed, which is an indication of the priority given to disadvantaged countries in terms of donor interventions.

Debt relief and a moratorium on debt services are other forms of external support. The World Bank, the IMF, the G20, the AfDB and all Paris Club creditors granted debt relief to 18 LICs in Africa as part of the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust. The IMF also activated emergency lending facilities for African countries. China, in turn, introduced a series of debt relief and debt service suspension measures for African countries. However, with African countries having incurred more than $350 billion in debt, the debt forgiveness and relief measures represent modest support given LICs’ enormous financial needs. There are also concerns that creditors could in the future penalise those African countries requesting debt relief. Mutize notes that most African countries eligible for a debt moratorium have so far refused to apply because of the risk of credit rating downgrades.8

There are also private philanthropic support measures. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has committed $1.6 billion over five years to ensure that the most vulnerable in the world can access a COVID-19 vaccine once developed. However, most philanthropic and bilateral support is aimed at health interventions, while economic support in many cases relies on the intervention of multilateral institutions. An analysis of trends in foreign aid and donor support shows that, in line with UNOCHA data, LICs in Africa have accessed some donor support, although this has been insufficient relative to their financial needs.

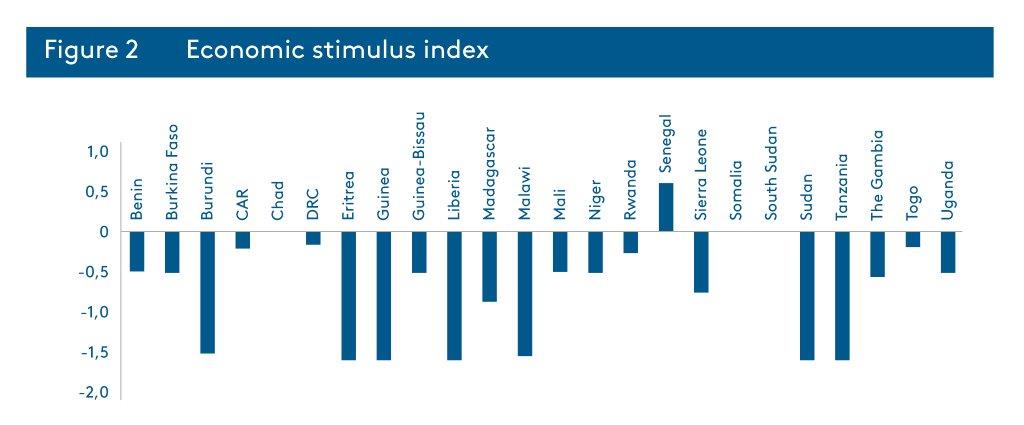

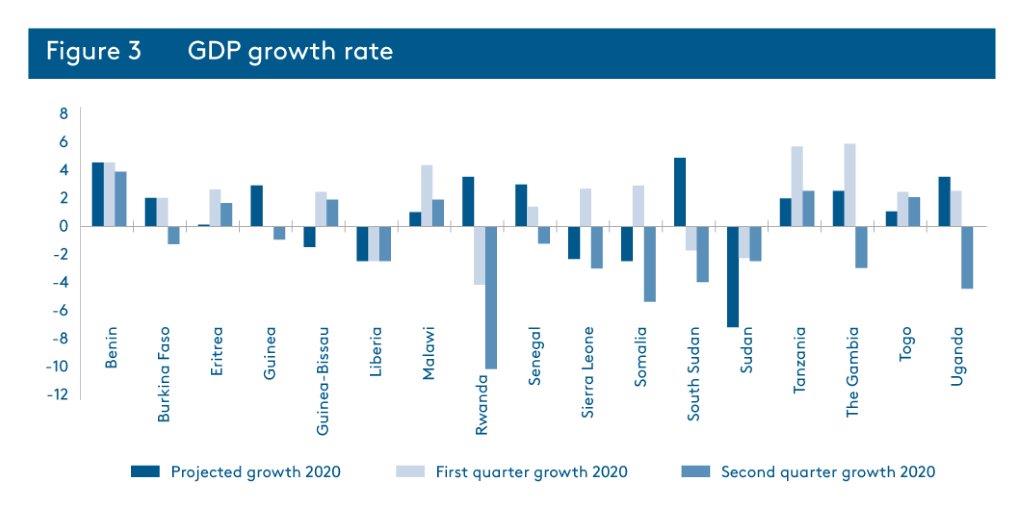

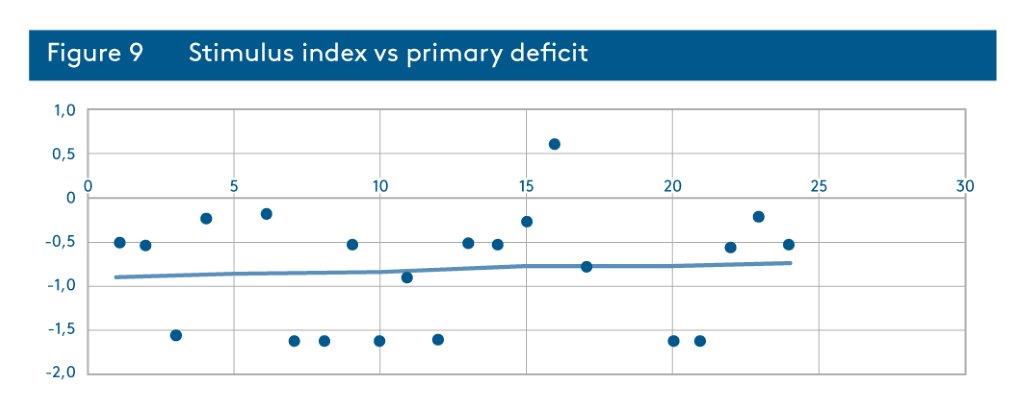

Given that the COVID-19 pandemic is still prevalent throughout the world, it is difficult to accurately gauge the effectiveness of various policy responses to date. Nevertheless, the policy interest that COVID-19 has stirred has prompted the capturing of much data using many indicators that have been useful in periodically tracking the virus’s economic and epidemiological effects. Elgin, Basbug and Yalaman9developed an economic stimulus index to track monetary, fiscal and exchange rate policy responses across countries. We used this index to assess the performance of LICs in Africa in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. We also compared the IMF’s projected growth rates among LICs, which are measures of the likely impact of COVID-19, to the actual growth rates in the first and second quarters of 2020.

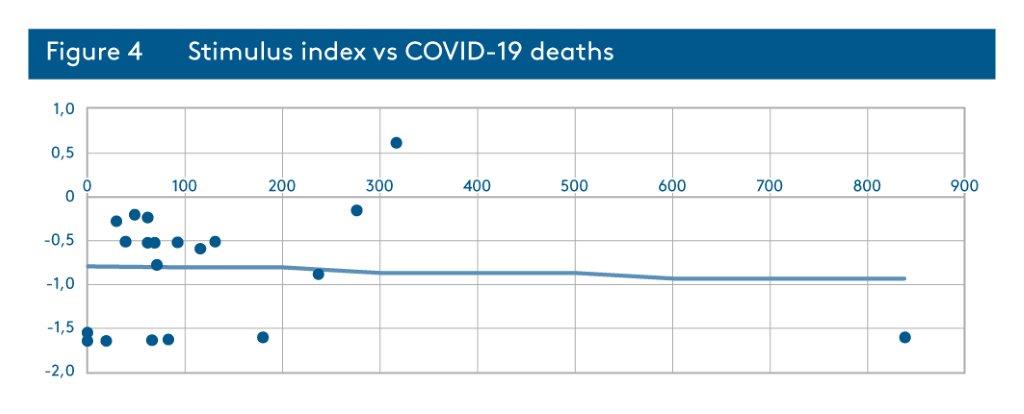

Furthermore, we correlated the stimulus index with key economic indicators prior to COVID-19 to assess the factors driving the observed country-by-country differences in policy design. The variables examined included: debt level, inflation and revenue over five years (2015–19) prior to the pandemic. High debt levels might constrain effective policy responses because of limited fiscal space. A similar argument holds for revenue; as better income streams are key to being able to pursue a countercyclical policy. In addition, inflation reduces the extent to which the monetary authority can push for an expansionary policy. Lastly, we compared the stimulus index to the incidence of and deaths from COVID-19. The results are reported in the Appendix.

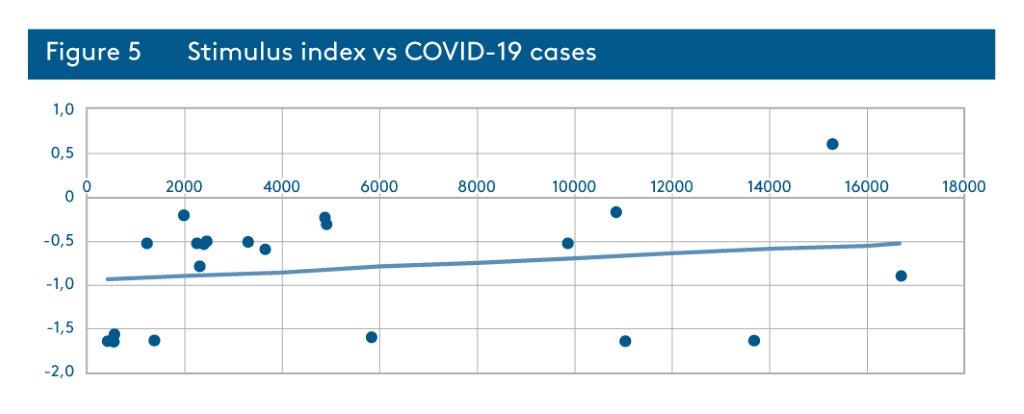

The analysis showed that the economic response has been weak across African LICs, with all countries (except Senegal) recording a negative score. Similarly, comparing the actual and projected growth rates revealed that many LICs’ growth rates have been worse than projected – especially in the second quarter of 2020, which coincided with the peak of the COVID-19-induced lockdowns. We found the stimulus index to be positively correlated with the number of COVID-19 cases, while the number of deaths showed a negative but nevertheless weak relationship. This suggests that countries’ response levels are driven by the incidence of the virus and not the death rate.

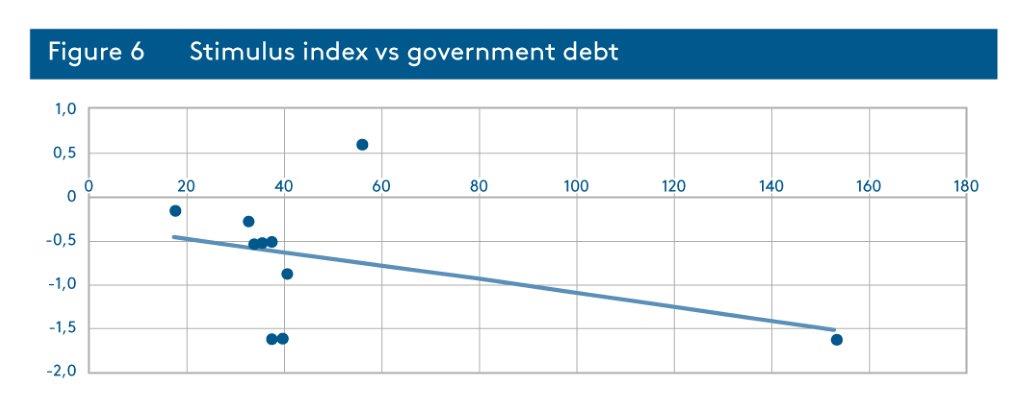

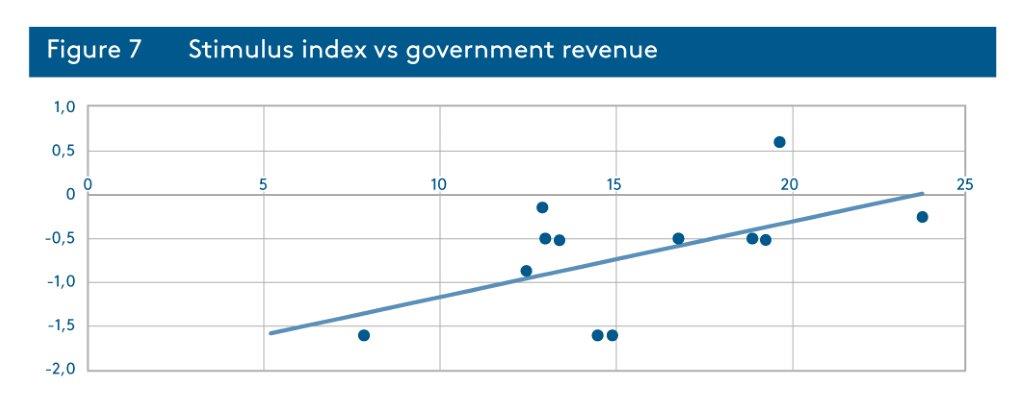

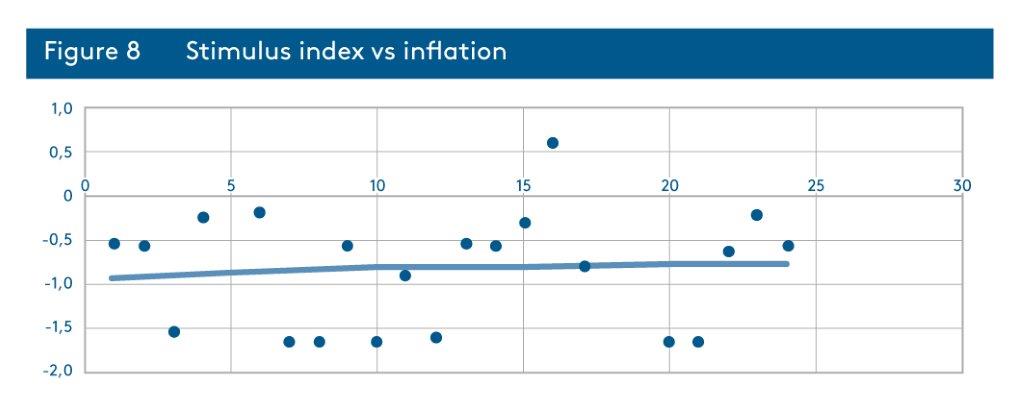

Countries with high debt levels before the crisis had lower scores on the stimulus index, while those with high revenue levels had higher scores. This aligns with the argument that limited fiscal space constraints LICs’ macroeconomic responsiveness. In the same vein, the stimulus index is lower among countries with high inflation before the pandemic, again illustrating that a weak macroeconomic environment is a major constraint to effective policy responses to COVID-19. Overall, the weak economic response among LICs in Africa is a manifestation of past economic problems. This finding is supported by the literature on the importance of initial conditions for economic development.10

The COVID-19 crisis bears some resemblance to the GFC. For LICs, both came in the form of an external shock emanating from developed countries and transmitted through trade and the economic interdependency among nations. The transmission mechanisms were also similar, with a decline in global trade, remittances, foreign aid and commodity prices dominating. However, the magnitude of COVID-19 and the speed with which it has unfolded have been much greater than those of the GFC. In just three months, COVID-19 managed to turn around the 2020 global economic outlook (output) from more than 3% to -3%.

With both the GFC and COVID-19, the majority of LICs in Africa pursued expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to absorb the economic shock. However, they had more space to use fiscal policy at the time of the GFC, as the crisis came after the implementation of the LIC debt forgiveness programmes. Furthermore, non-resource-dependent countries were only marginally affected by the GFC, with some even benefiting from lower fuel and food prices.11In fact, economic growth declined only slightly among African LICs during the crisis.

During the GFC, LICs responded to changes with macroprudential policies to strengthen the financial system. The response to COVID-19 has in turn centred on strengthening the health system and developing social security facilities for vulnerable groups. The donor support measures during the two crises were similar. In terms of development assistance, priority was given to fragile and post-conflict states. Multilateral institutions also introduced special facilities that African countries could tap, with the IMF, World Bank and AfDB providing facilities to improve trade, the financial system, foreign reserves and infrastructure. In addition, the IMF created Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to the value of $250 billion, which countries can access up to their IMF quota share. This has proved useful for LICs during the COVID-19 crisis. However, policy tools like debt forgiveness were of limited use during the GFC compared to their value during COVID-19. Overall, there were inadequate funds for African LICs to effectively respond to the two crises.

In terms of differences in economic policy responses, social palliatives were used in very few African countries during the GFC. Bilateral support was much more prevalent – although complementary to the multilateral support – during the GFC. In contrast, donor support for COVID-19 has largely come from multilateral institutions. In addition, COVID-19 has been greeted by a better-capacitated financial system (ie, capital reserves), whereas the financial sector was found wanting during the 2007–2008 GFC. Lastly, in African countries’ responses to the GFC, regional cooperation had a stronger role to play, especially in the area of monetary policy. African governments set up the Committee of Central and Regional Bank Governors (C-10) at the beginning of the GFC. During COVID-19, while there have been areas of coordination in health policy (eg, the Africa Taskforce for Novel Coronavirus) and fiscal policy (eg, the creation of a Continental Solidarity Anti-COVID-19 Fund), monetary policy has been less coordinated among African countries.

However, the economic impact of COVID-19 on LICs is expected to be greater owing to the slowdown in trade and economic activity, and unequal access to COVID-19 therapeutic treatments. In addition, while poverty levels did not rise in the face of the GFC, most research findings point to a sharp increase in poverty rates (for the first time in three decades) owing to COVID-19.12

A gradual reopening of the economy has been evident in all LICs. At the time of writing, the policy focus was centred on recovery efforts. In this phase, fiscal and monetary policies will remain not only relevant but also crucial. However, several pertinent issues and lessons from the relief phase should guide recovery efforts and policy responses.

Inability to harness multiple policy instruments: Unlike high-income and middle-income countries that simultaneously deployed fiscal and monetary policies in response to COVID-19, most African LICs have been able to effectively use only one instrument. High debt levels and inflation, as well as other structural issues, have limited policy options. In the long run, the structural bottlenecks impeding the effective implementation of economic policies by LICs need to be addressed using a more nuanced approach. This will require reforming economic institutions and processes to drive inclusive growth. An important focus area is the independence of monetary and debt management authorities, which is crucial for fiscal sustainability and controlling inflation.

Importance of a switch to a data-driven approach: The initial response to the pandemic in most African countries was simply to copy the template from developed countries.13For example, lockdowns and economic shutdowns were reversed in many countries after recognition of the limited capacity of governments to provide palliatives. This led to a more data-driven approach, which is consistent with countries’ economic structure and disease prevalence. Similarly, recovery efforts should be anchored on the same data-driven approach, with the interests of vulnerable populations prioritised.

Need for better leveraging of international cooperation: Official development assistance plays a prominent role in African LICs’ economic responses. It will continue to be crucial for COVID-19 recovery efforts, especially in the case of fragile states that have limited capacity to mobilise domestic resources and are heavily reliant on external support and trade. Nevertheless, it is important to look inwards to the Global South and other countries in Africa. Intra-Africa trade is one area that LICs can leverage for stronger resource mobilisation and growth. For example, the opportunities created by the African Continental Free Trade Area, which is expected to commence on 1 January 2021, can be tapped by LICs.

Rethinking of economic structure: Some of the structural hurdles facing LICs in Africa, which COVID-19 has exposed, include weaknesses in the digital economy, a lack of financial and social inclusion, and poorly developed domestic financial markets. Also, contrary to conventional economic thinking, many LICs follow pro-cyclical policies – ie, not saving during an economic boom – which a countries’ preparedness and ability to respond effectively to a sudden economic crisis. A long-term process to address these failures needs to be set in motion as part of countries’ broad recovery plans.

This analysis has revealed that economic policy responses among LICs in Africa have been suboptimal in the face of existing, pre-pandemic economic challenges. These challenges, which have simply been amplified by the crisis, include poor fiscal positions, deficiencies in human capital development, and a general absence of crucial hard and soft infrastructure. It is therefore important that recovery efforts are used as a springboard for long-term development across the continent. Indeed, a holistic and comprehensive intervention in these areas should be front and centre of the conversation on economic recovery going forward.

This article was first published at Compra

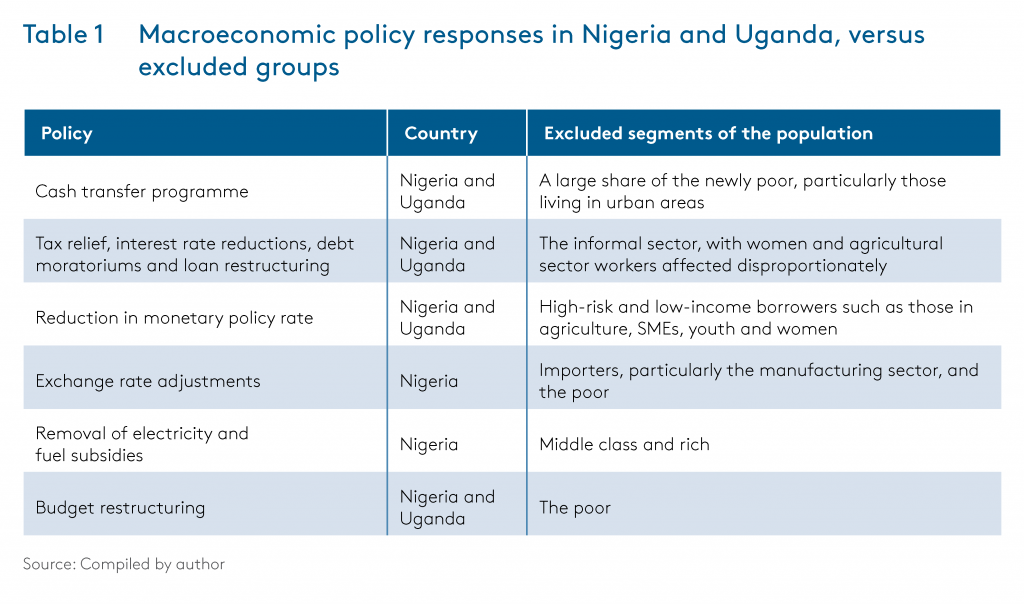

Countries across the world have deployed macroeconomic policies to address the negative economic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown measures. However, these policies can have different outcomes for various segments of the population. This policy briefing assesses the channels through which macroeconomic policy responses in Nigeria and Uganda negatively affect or exclude specific groups, with the aim of resetting policies to achieve more inclusive outcomes that will support economic growth and development in the post COVID future. It finds that the urban poor and the informal sector are being excluded as a result of the poor coverage of cash transfer programmes and the implementation of policies mostly applicable to the formal sector. Loans to low-income borrowers are not likely to increase despite downward revisions to the monetary policy rate, while importers and poorer households will be the worst hit by exchange rate adjustments in Nigeria. While the middle class and rich are affected by the removal of subsidies in Nigeria, those living in poverty do not benefit from the budget restructuring in Uganda.

While economic recessions can have significant distributional effects, the macroeconomic policies adopted to counteract recessions can have varying outcomes on different segments of the population. As such, a government’s policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic can increase inequalities through key transmission channels. Data from the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Response Tracker shows that 89% of African countries have deployed fiscal stimuli for vulnerable populations, including those who have lost their livelihoods as a result of the crisis and low-income households. Liquidity has been provided to affected businesses and sectors such as tourism, hospitality and aviation in 92% of African countries.1Yet the design and implementation of such macroeconomic policies are often neutral, thus allowing existing forms of inequality to worsen. This policy briefing assesses the ways in which macroeconomic policy responses in Nigeria and Uganda negatively affect or exclude specific groups, particularly youth, women, the informal sector and the newly poor (especially in urban areas). In addition, businesses in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors, as well as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), are negatively impacted by these policy responses. The aim of this policy briefing is to help reset policies to achieve more inclusive outcomes that will support economic growth and development in the post-COVID future.

The analysis covers the fiscal and monetary policies deployed by the Nigerian and Ugandan governments and shows how these policies could lead to worse outcomes for certain segments of the population. The dimensions of disparities considered for individuals include age, gender, place of residence (rural or urban) and income category; for businesses the dimensions include size of business and sector (agriculture, manufacturing and services).

Poor coverage and cash transfer targeting exclude the urban poor. Both Nigeria and Uganda have expanded existing cash transfer programmes to deliver funds to the poor and those most vulnerable to the pandemic. Nigeria has scaled up its programme by increasing its National Social Register of poor and vulnerable households by 1.1 million households to 3.7 million households (15.5 million individuals).2The government gives NGN35,000 ($13) per month to the poorest households for at least three years to ensure food security. Similarly, since the pandemic the Ugandan government has increased funding for the Urban Cash for Work Programme (UCWP) to UGX4130 billion ($35 million) and social welfare programmes by UGX 152 billion ($41 million), with an additional UGX 45 billion ($12.03 million) for government relief aid in response to COVID-19 and another UGX 107 billion ($28.6 million) for the Social Assistance Grants for Empowerment (SAGE), targeting the elderly.5Under SAGE, each beneficiary is paid UGX 25,000 ($6.7) per month. The programmes have also been expanded, with the UCWP covering an additional 500 000 individuals and SAGE an additional 71 districts.6

Despite these expansions, these cash transfer programmes underperform significantly in terms of size, coverage and targeting. At 0.002% and 0.00017% respectively, spending on cash transfer programmes as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) in Uganda and Nigeria is meagre.7As a result, the programmes’ coverage falls significantly short. Based on the 2019 Nigerian Living Standards Survey (NLSS), about 83 million Nigerians are living in poverty, implying that 81% of poor people are excluded from the National Social Register.8Similarly, in Uganda 10 million people are living in poverty, based on the household survey in 2016/17.9However, only 1.5 million people benefited from the UCWP.10Furthermore, the amounts allocated do not cover the cost of a basic nutritious diet per month for a household of five.

Given the strategy of identifying poor households in Nigeria – using the National Social Register to select the poorest 30% of households in states with high poverty levels – the beneficiaries are mostly members of agrarian and rural communities. Yet the newly poor in urban areas, such as SME owners, drivers and cleaners, are most susceptible to income shocks caused by the pandemic, making the targeting of the cash transfer programme sub-optimal. Even in Uganda, the majority of the additional funds is targeted at the UCWP and SAGE. However, the former is likely to experience delays owing to the pandemic and the elderly are not particularly prone to income shocks from the pandemic. In addition, the eligibility age for the SAGE programme was increased from 65 to 80 years, thus reducing the size of the target population.

Most of the policies deployed – tax relief, interest rate reductions, debt moratoriums and loan restructuring – do not impact the informal sector, affecting women and agricultural workers disproportionately. While both countries are using a range of policies to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on individuals and businesses, these policies mostly benefit formal sector workers and businesses. Yet the informal sector accounts for 65% and 50% of Nigeria and Uganda’s GDP respectively, and employs 80% of the labour force in both countries.11Although not all informal workers are poor, they face a higher risk of poverty, are more susceptible to income shocks than their counterparts in the formal sector, and live in urban areas with higher living costs and little recourse to subsistence agriculture. With women accounting for 74% of workers (non-agriculture)12in the informal sector in subSaharan Africa, and the agricultural sector contributing significantly to the informal economy, women and those who work in agriculture do not benefit from these relief policies.

Downward revisions to central banks’ policy rates have failed to reflect in the lending rate of commercial banks, particularly affecting high-risk and low-income borrowers such as small-scale farmers, SME owners, youth and women. Expansionary monetary policies have been adopted, with the Central Bank of Nigeria reducing its monetary policy rate from 13.5% to 11.5% and the Bank of Uganda reducing its rate from 9% to 7%.13However, interest on loans made by commercial banks remains high, affecting high-risk and low-income borrowers. Owing to externally determined conditions such as weather and price volatility, workers in the agricultural sector are widely viewed as high risk, making it difficult to reduce the lending rate offered to them. In addition, segments of the population with low income and limited access to collateral such as SME owners, youth and women are less likely to be offered favourable loan terms.

Exchange rate adjustments in Nigeria are having a direct negative impact on importers and an indirect impact on poorer households through rising domestic inflation. With crude oil contributing about 80% of foreign exchange earnings,14the foreign exchange shortage owing to the decline in demand for oil has put pressure on the exchange rate, leading to the devaluation of the naira. The official exchange rate was first adjusted from NGN 307/$1 to NGN 361/$1, and then to NGN 380/$1.15These revisions have led to a rise in the price of imports, particularly affecting the manufacturing sector, which is heavily dependent on imported raw materials and intermediate goods. As a result, domestic prices are rising, with implications for the purchasing power of poor citizens.

Removal of electricity and fuel subsidies is having a disproportionate impact on the income of the middle class and rich. As a result of the pandemic, the Nigerian government has increased the fuel price from NGN 121 ($0.32) to NGN 162 ($0.43) per litre. The electricity tariff has gone from NGN 30.23 ($0.08) to NGN 62.33 ($0.16) per kwh (for consumers with an electricity supply above 12 hours per day). The drop in government revenues necessitated the removal of these electricity and fuel subsidies. Given that poor households were not the main beneficiaries of these subsidy programmes – 43% of Nigerians, mostly those living in rural areas, do not have access to electricity16and low-income households use relatively less fuel and electricity – the subsidy removal is likely to reduce the disposable income of the middle class and rich.

Budget restructuring in Uganda does not support those living in poverty. Neither the supplementary budget passed before the end of the 2019/20 fiscal year nor the 2020/21 budget caters adequately for those people most affected by the pandemic. The main beneficiaries of the supplementary budget are SMEs able to access funds from the Uganda Development Bank (UGX 455 billion [$122.1 million]) and suppliers of goods to government through the clearing of domestic arrears (UGX 223 billion [$59.9 million]), with allocations to social protection coming in third at UGX 105 billion ($28.2 million).17Similarly, the sectors with the biggest increases in budget allocation in 2020/21 are water and environment (35%), science, technology and innovation (30%), local government (28%) and public administration (26%).18Even in Nigeria, the 2020 budgetary allocations to works, power and housing; agriculture; and information and communications increased relative to the 2019 budget, while there were reductions in the allocations to education (16%), health (11%) and humanitarian affairs (12%).19

Existing forms of inequality can deepen in the face of a major crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic – and as a result of the neutrality of policies deployed in response to the crisis. The macroeconomic policy responses of the Nigerian and Ugandan governments have had the unintended effect of excluding youth, women, the informal sector and the newly poor (particularly in urban areas). At the same time, the removal of electricity and fuel subsidies are affecting the middle class and rich disproportionately, given that these groups were the beneficiaries of the initial subsidy programme. In addition, businesses in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors, alongside SMEs, are likely to be negatively affected by some of the policy responses.

Excluding a wide range of the population will not only affect present living conditions and wellbeing but also limit the private sector spending required to stabilise the economy and avert or recover from a recession. While the governments of both countries have increased spending in order to counteract the drop in private sector consumption and investment, taking on debt for this purpose, debt sustainability remains a pressing issue. As evidenced by their current budgets, debt servicing takes up a considerable amount of government revenue with implications for development spending.

In future, response strategies should be context-specific and take into consideration existing inequalities in order to provide a more tailored and inclusive approach. This will ensure that all segments of the population are reached, lead to efficiency in spending and limit negative welfare impacts.

Governments should revise their budget allocations to healthcare and social protection in order to address the needs of vulnerable people and affected businesses. In the short term, this can be done by using newly available resources (such as unused travel allowances), funding from the private sector and/or international partners, sovereign wealth funds, national reserves and other sinking funds. In the long term, the tax capacity of both countries needs to be improved to allow government to mobilise adequate domestic resources to meet current needs and build fiscal buffers.

Given the widespread access to mobile phones and the ease of electronic transfers, both countries should adopt electronic platforms to distribute cash to hard-to-reach populations. Countries that used electronic transfers extensively before the pandemic, such as Kenya, have been able to use these platforms for cash payments during the pandemic. National databases can be used to effectively identify vulnerable people.

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, half of new solar and wind installations are cheaper than fossil fuel energy sources,20making renewable energy more affordable on average. Thus, promoting investment in and use of renewable energy is crucial, particularly for low-income households.

The author is grateful to Dr Susan Kavuma for peer reviewing this policy brief.

This article was first published at Compra