Rapid digitalization has the potential to enhance structural transformation among African countries as well as galvanize progress on regional developments like the recent African Continental Free Trade Area. However, these benefits are not guaranteed given the multipronged threats in the digital space that can limit trust and curtail the adoption of such innovations. Indeed, the platform-based business model that dominates the digital economy raises fundamental issues about data protection and citizens’ privacy. Likewise, the monopoly market structure that characterizes the digital platforms implies a winner-takes-all paradigm, leaving less for developing economies. Rising cybercrime, ransomware, and digital identity theft pose significant threats: African economies lost over $3.5 billion through cyberattacks in 2017 alone. The more worrisome threat emanates from the rise in the number of African states with spyware, surveillance, censorship, and internet shutdowns. This trend is affecting trust in the digital space.

Africa enters 2022 with a long and urgent to-do list. In this blog, Adedeji Adeniran joins other experts to outline key political, economic, security and health issues the continent must contend with as it maps its COVID-19 recovery and post-pandemic reality.

TRADE

Africa remains underrepresented in global trade, accounting for 2.19% of global exports and 2.85% of global imports in 2020. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) can reverse this trend if it is effectively implemented. Launched in January 2021, the agreement is a crucial step towards boosting regional trade and economic development, but full trading activity is yet to commence due to ongoing negotiations on various protocols.

Concluding negotiations on the agreement on rules of origin (the “legal provisions used to determine the nationality of a product in the context of international trade”) and protocols on trade in e-commence and services is a priority. While these are unavoidably complex, the strain on economic growth due to COVID-19 necessitates the acceleration of the AfCFTA.

The newly launched Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) holds potential: the platform, developed by Afreximbank and the AfCFTA Secretariat, is expected to bolster intra-African trade by facilitating simpler and secure cross-border payments and reducing payment transaction costs by $5 billion annually. The African Trade Gateway, AfCFTA Adjustment Facility and Trade Finance Facility are also expected to take off, making 2022 a promising year for the effective operation and success of regional economic initiatives. However, it will take much longer for the continent to fully recover from the economic shocks of the pandemic.

The efforts by world leaders – or lack thereof – has left us with only a 60% chance of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5ºC by 2050. A chance that the African countries and Small Island Developing States cannot afford to take. Their unfavourable positioning in the climate crisis will cause a continuation of escalating sovereign debt and climate-induced loss and damage, and as a consequence vulnerable communities will pay the highest price.

The goal of COP26 was clear: the summit was meant to achieve a deal to provide a fighting chance to avert the worst impacts of climate change. While, initially stronger commitments were tabled, it was significantly watered down to reflect contentious wording on the fossil fuel sector and weak agreements on financial support to poor and vulnerable nations. The lack of adequate action has left the majority of people dissatisfied.

Global climate action since the Paris Agreement in 2015 has been disappointing. As the UN Secretary General, António Guterres, noted in his opening speech at the COP26, the last published report on Nationally Determined Contributions (commitments by each country to reduce carbon emissions, NDCs) shows that current commitments by the parties still condemned the world to a calamitous 2.7 ºC increase.

COP26 delivered new climate change mitigation commitments (such as the Glasgow Climate Pact, Pledge to End Deforestation by 2030, The Global Methane Pledge, and the Pledge to Phase out Coal) and financing pledges ($130 Trillion Global Finance Pledge, $10.5 Billion Fund for Emerging Economies, and $1.7 Billion to Indigenous Peoples). Yet, the outcomes have been grounded with the same narrative that has failed to yield any tangible results to date: a narrative that is rooted in economic imperatives and not equality.

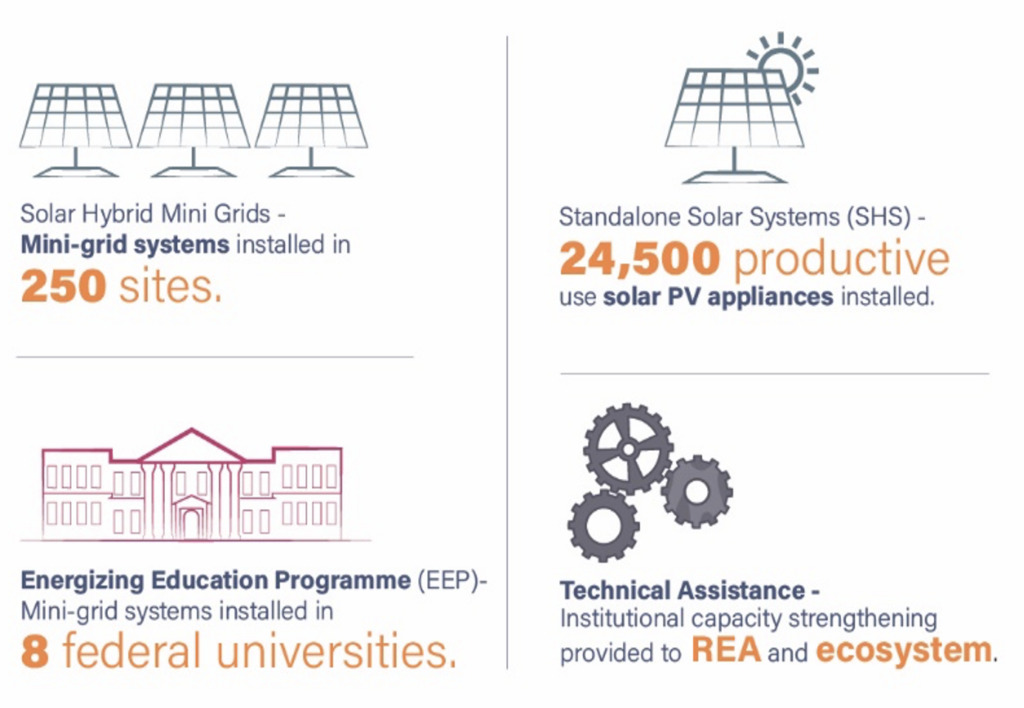

The Nigerian Electrification Project (NEP) is a federal government scheme designed in 2018 with the World Bank, the African Development Bank (AfDB), and other partners to provide energy access to under- and unserved communities in Nigeria using renewable sources. It is a private sector-driven nationwide initiative implemented by the country’s Rural Electrification Agency (REA). The Project promotes electricity access for households, micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), and public education institutions. It specifically aims to provide cost-effective power to 250,000 MSMEs and 1 million households through off-grid and mini-grid systems by 2023 via four main components:1

Read more- Energy for Growth Hub

How can policymakers spur communal investment in education when benefits are shared among all, regardless of contributions? A case study of the Igbajo community in Nigeria’s Osun State finds an answer in the strength of communal ties.

Empirical evidence has highlighted that community involvement can play a key role in expanding access to, and the quality of, education. From the maintenance of better and safer schooling facilities to the creation of more responsive school governance, there is broad agreement that when parents and the broader community are involved in the operation of local schools, higher standards are kept. Yet like most voluntary activities and public goods provision, mobilising and aggregating at times disparate community members’ interests and priorities faces the typical free-rider problem – that is, an inefficient distribution of goods resulting from individuals being able to access the good without paying their share of the costs. Given that the benefits of education are shared irrespective of contribution, investment – of time and money – is often undersupplied. However, this challenge can be surmountable: this blog highlights a case study of community-driven efforts to improve education, drawing conclusions on the replicability of similar cases elsewhere.

The economic literature tends to suggest solutions to free-rider problems that involve some contractual or statutory commitments. For instance, tax laws are designed to overcome free-riding in the provision of public goods and ensure that all – at least in theory – pay their fair share. Similarly, when it comes to the private provision of public goods, proposed solutions often involve the agreement of contracts that make contribution to the common good a Nash equilibrium in a theoretical game-like scenario.

There is, however, a different form of commitment that, when leveraged correctly, can help overcome issues associated with free-riding at a communal level. Sociological literature from the Durkheimian school has long emphasised the importance of group inclusion to individuals. Commitments to the well-being of the community through appeals to ‘groupish' identity and pride can hence be powerful tools to be leveraged in the struggle to generate high levels of community involvement in local education.

In this regard, the example of the Igbajo community in Nigeria’s Osun State can provide an important instructive case study about the potential of communal ties to facilitate the overcoming of free-riding and choice aggregation problems in education.

The town of Igbajo made history in 2009 with the establishment of the first community institution for tertiary education in Nigeria. The high costs and challenging logistics of facilitating a post-secondary institution are enormous in Nigeria, such that only the government and large-scale for-profit private sector investment are considered viable sources for tertiary education funding. This has restricted community involvement in education to primary and secondary education and, at most, to often-ineffective attempts at lobbying for post-secondary education. While, of course, the story of Igbajo includes elements of a paradigmatic tale of local pride and parochialism, it would be hard to put it all down to a natural sense of community pride among Igbajo residents. After all, there is nothing that obviously confines such a quality to any community. Naturally, local pride is expected everywhere.

The reasons why local pride resulted in tangible action can be gleaned in conversation with the key community members behind the project. It was not just pride that guided their decisions – it was a multiplicity of factors that explained the process investing massively in such a project.

First, external factors such as low government support helped generate a sense of being slighted that led to the aggregation of individual interests around a single priority. The community had, in the past, lobbied for the creation of a tertiary school and a local government secretariat as well as for other socio-economic amenities, losing out each time to competing communities. The perceived external threat of neglect creates strong internal cohesion and coordination and adds an elements of urgency to community intervention. This, therefore, can serve as a non-economic incentive to coordinate (or subordinate) individual choices to the collective good.

Moreover, the community has a deliberative system of decision making which proved useful in coordinating individual actors. Through existing social networks within the community, like the Igbajo Social Circle and Igbajo Development Association down to annual kindred meetings, the system of frequent communal interaction makes it logistically simpler for coherent community-level positions to emerge, and, crucially, also serves as a form of peer pressure that encourages active participation and lower tendency to free ride. Further still, the deliberative setting engenders a mechanism for civic responsibility and open recognition of especially-active ‘champions’. This, in turn, creates incentive for individuals to seek the recognition of their peers by taking on larger roles that help drive the initiative. Again, this form of incentive would not have emerged without clear mechanisms of community-level interaction (and pressure).

Indeed, examples like that of Igbajo provide the anecdotal empirical support that underpin the objectives of the RISE Nigeria project. By organising deliberative Education Summits, engaging local populations, and disseminating results widely, RISE aims to test whether institutionalising forms of community involvement and facilitating knowledge generation and dissemination can be useful in sparking forms of community pride and inter-community ‘positive competition’. Does bringing communities together and providing them with information about how they compare to other neighbouring groups create enough social pressure to encourage unselfish behaviour? Can we use informative and deliberative institutions to leverage a Durkheimian collective identity and overcome free riding in education at the community level?

These are important questions that RISE Nigeria seeks to clarify through the lens of political economy experiments. Evidence from this would have important implications for development practitioners around the world. Given the potential of community involvement to spur education, and the obvious implications that might have on broader socioeconomic development, understanding how the interactions work and how the institutional structure can strengthen inter-communal bonds could lay the groundwork for important progress in galvanizing more community engagements in education.

This article was first published on RiSE