The manufacturing sector PMI declined from 58.3 points to 51.1 points between February and March 20201. The slowdown was triggered by reduced growth in 7 subsectors including electrical equipment, chemical and pharmaceutical products, primary metals and non-metallic mineral products. Similarly, the non-manufacturing PMI index declined to 49.2 percent, falling below the 50 percent threshold for the first time in over 2 years1. The overall contraction is due to the depression in global economic activity which has led to a reduction in new orders, inventory and consequently employment levels across the manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors. In the coming months, the reduced activity across both sectors is expected to continue as a result of the decline in global demand for exports and the reduction in local consumption. In the meantime, some manufacturers can switch to producing essential commodities that are required to tackle the pandemic. In addition, the cash transfers by the government should be distributed to manufacturing and non-manufacturing workers that would be laid off or furloughed as a result of the pandemic.

Between January and February, Nigeria’s external reserves declined from US$37.2 billion to $35.5 billion, its lowest in over 2 years1. Although the reserve level remains above the $30 billion benchmark set by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN)2, the reserves have depleted considerably by 2.03% month-on-month. Since the beginning of the year, external reserves have steadily declined, falling by a total of $2.38 billion in 2020. The recent decline stems from a fall in crude oil prices occasioned by a slowdown in global economic activities following the Corona virus outbreak. Perhaps in reaction to the declining external reserves, CBN has decided to suspend the multiple exchange window policy which was hitherto used to determine the value of the Naira. The decision to collapse the multiple window rates is a step in the right direction as this will forestall some inherent demerits in using different rates which include currency roundtripping, non-reflective production costs, rent-seeking and corruption.

With 1.39 million coronavirus cases and 79,382 deaths globally, the world continues to battle the COVID-19 pandemic. Even before the outbreak, the outlook for the world economy—and especially developing countries like Nigeria—was fragile, as global GDP growth was estimated to be only 2.5 percent in 2020. While many developing countries have recorded relatively fewer cases—Nigeria currently has 238 confirmed cases and 5 deaths as of this writing—the weak capacity of health care systems in these countries is likely to exacerbate the pandemic and its impact on their economies.

THE IMPACT ON THE NIGERIAN ECONOMY

Before the pandemic, the Nigerian government had been grappling with weak recovery from the 2014 oil price shock, with GDP growth tapering around 2.3 percent in 2019. In February, the IMF revised the 2020 GDP growth rate from 2.5 percent to 2 percent, as a result of relatively low oil prices and limited fiscal space. Relatedly, the country’s debt profile has been a source of concern for policymakers and development practitioners as the most recent estimate puts the debt service-to-revenue ratio at 60 percent, which is likely to worsen amid the steep decline in revenue associated with falling oil prices. These constraining factors will aggravate the economic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak and make it more difficult for the government to weather the crisis.

AGGREGATE DEMAND WILL FALL, BUT GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE WILL RISE

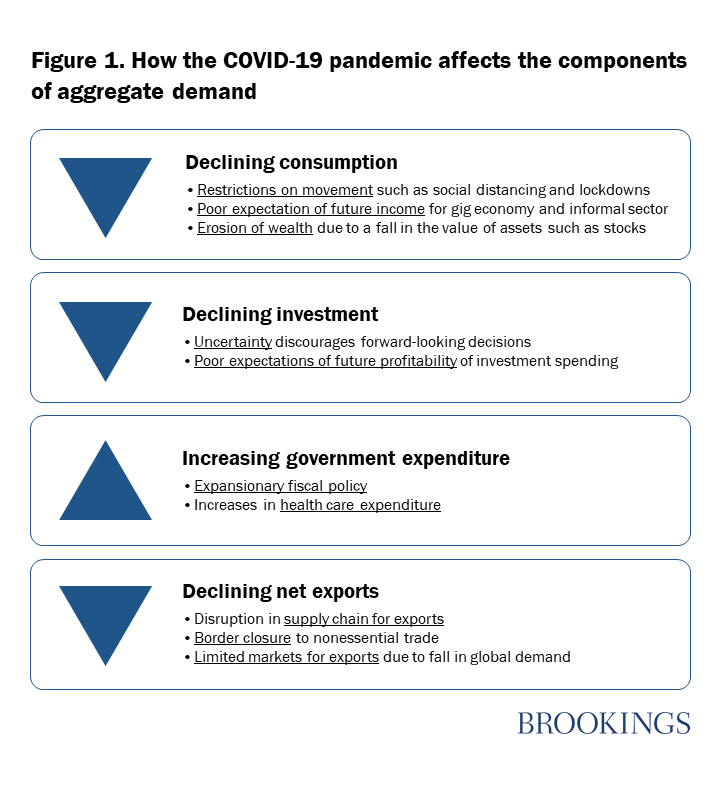

In Nigeria, efforts were already being made to bolster aggregate demand through increased government spending and tax cuts for businesses. The public budget increased from 8.83 trillion naira ($24.53 billion) in 2019 to 10.59 trillion naira ($29.42 billion) in 2020, representing 11 percent of the national GDP, while small businesses have been exempted from company income tax, and the tax rate for medium-sized businesses has been revised downwards from 30 to 20 percent. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 crisis is causing all components of aggregate demand, except for government purchases, to fall (Figure 1).

The fall in household consumption in Nigeria will stem from 1) partial (or full) restrictions on movement, thus causing consumers to spend primarily on essential goods and services; 2) low expectations of future income, particularly by workers in the gig economy that are engaged on a short-term/contract basis, as well as the working poor in the informal economy; and 3) the erosion of wealth and expected wealth as a result of the decline in assets such as stocks and home equity. The federal government has imposed a lockdown in Lagos and Ogun states as well as Abuja (which have the highest number of coronavirus cases combined). Subnational governments have quickly followed suit by imposing lockdowns in their states. Nigeria has a burgeoning gig economy as well as a large informal sector, which contributes 65 percent of its economic output. Movement restrictions have not only reduced the consumption of nonessential commodities in general, but have affected the income-generating capacity of these groups, thus reducing their consumption expenditure.

Investments by firms will be impeded largely due to the uncertainties that come with the pandemic-limited knowledge about the duration of the outbreak, the effectiveness of policy measures, and the reaction of economic agents to these measures—as well as negative investor sentiments, which are causing turbulence in capital markets around the world. Indeed, the crisis has led to a massive decline in stock prices, as the Nigerian Stock Exchange records its worst performance since the 2008 financial crisis, which has eroded the wealth of investors. Taking into consideration the uncertainty that is associated with the pandemic and the negative profit outlook on possible investment projects, firms are likely to hold off on long-term investment decisions.

On the other hand, government purchases will increase as governments, which typically can afford to run budget deficits, utilize fiscal stimulus measures to counteract the fall in consumer spending. However, for governments that are commodity dependent, the fall in the global demand for commodities stemming from the pandemic will significantly increase their fiscal deficits. In Nigeria’s case, the price of Brent crude was just over $26 a barrel on April 2, whereas Nigeria’s budget assumes a price of $57 per barrel and would still have run on a 2.18 trillion naira ($6.05 billion) deficit. Similarly, with oil accounting for 90 percent of Nigeria’s exports, the decline in the demand for oil and oil prices will adversely affect the volume and value of net exports. Indeed, the steep decline in oil prices associated with the pandemic has necessitated that the Nigerian government cut planned expenditure. In fact, on March 18, the minister of finance announced a 1.5 trillion naira ($4.17 billion) cut in nonessential capital spending.

The restrictions on movement of people and border closures foreshadow a decline in exports. Already, countries around the world have closed their borders to nonessential traffic, and global supply chains for exports have been disrupted. Although the exports of countries that devalue their currency due to the fall in the price of commodities (like Nigeria), will become more affordable, the limited markets for nonessential goods and services nullifies the envisaged positive effect on net exports.

WHAT ARE THE POLICY RESPONSES BY THE NIGERIAN GOVERNMENT?

Already, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has arranged a fiscal stimulus package, including a 50 billion naira ($138.89 million) credit facility to households and small and medium enterprises most affected by the pandemic, a 100 billion naira ($277.78 million) loan to the health sector, and a 1 trillion naira ($2.78 billion) to the manufacturing sector. In addition, the interest rates on all CBN interventions have been revised downwards from 9 to 5 percent, and a one-year moratorium on CBN intervention facilities has been introduced, effective March 1.

With oil being Nigeria’s major source of foreign exchange, amid the steep decline in oil prices, the official exchange rate has been adjusted from 306 to 360 naira. The exchange rate under the investors and exporters (I&E) window has also been adjusted from 360 to 380 naira in order to unify the exchange rates across the I&E window, Bureau de Change, and retail and wholesale windows. Furthermore, the government has introduced import duty waivers for pharmaceutical companies and increased efforts toward ensuring that they receive forex.

WHAT OTHER POLICY RESPONSES CAN BE IMPLEMENTED?

Given the size and scope of the economic impact of the pandemic, there is the need to implement other recovery strategies to stimulate demand. Thus, we recommend the following fiscal and monetary policy measures:

The COVID-19 pandemic is a wake-up call to policymakers as the unusual and unprecedented nature of the crisis has made it impossible for citizens to rely on foreign health care services and more difficult to solicit for international support given the competing demand for medical supplies and equipment. A more integrated response spanning several sectors—including the health, finance, and trade sectors—is required to address structural issues that make the country less resilient to shocks and limit its range of policy responses. In the long term, tougher decisions need to be made, including but not limited to diversifying the country’s revenue base away from oil exports and improving investments in the health care sector in ensuring that the economy is able to recover quickly from difficult conditions in the future.

This article was first published at Brookings.edu

The Global Health Hazards and Economic Impacts of COVID-19

In December 2019, a cluster of pneumonia cases from an unknown virus surfaced in Wuhan, China. Based on initial laboratory findings, the disease named Coronavirus disease 2019 (abbreviated as COVID-19), was described as an infectious disease that is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. The COVID-19 outbreak has since spread to about 196 countries and territories in every continent and one international conveyance across the globe. While there are ongoing efforts to curtail the spread of infection which is almost entirely driven by human-to-human transmission, it has accounted for over 400,000 confirmed cases with over 18,000 deaths[1].

Beyond the tragic health hazards and human consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic uncertainties, and disruptions that have resulted come at a significant cost to the global economy. The United Nations Trade and Development Agency (UNCTAD) put the cost of the outbreak at about US$2 trillion in 2020. Most central banks, finance ministries and independent economic experts around the world have taken solace in the prediction that the impacts might be sharp but short-lived, and economic activities would return to normal thereafter. This line of thought mirrors the thinking of the events that shaped the 2007 global financial crisis. However, it is quite instructive to note that the 2007 crisis which emanated from the United States’ subprime mortgage crisis was mainly an economic phenomenon, with its fallout spreading across many regions of the world. When compared to COVID-19, the 2007 crisis could be described as minor and manageable. The tumultuous events that COVID-19 had spread across the globe cut across every facet of human existence and the consequences may linger beyond the second half of 2020.

The slowdown in the global economy and lockdown in some countries, such as Italy, Spain and most Eurozone economies and beyond, as a result, COVID-19 has also taken its toll on the global demand for oil. The decline in oil demand is estimated to surpass the loss of nearly 1 million barrels per day during the 2007-08 recession. This is also coming at a time when two key players in the global oil industry – Russia and the OPEC cartel – are at loggerheads on the decision to cut output. The unequivocal oil price war started between these two global oil market giants may have more dire consequences on the oil price that has started to dive. .

Sector-specific implications and impacts could vary. For example, the impacts on the global aviation and tourism sectors are a result of the implications of the pandemic on global travel. As discretionary spending by consumers continues to decline, cruise companies, hotels, and hospitality are facing declining demand and patronage. For example, in Hungary alone, about 40 to 50% of hotel reservations have been canceled. Also, the pandemic is placing up to 8 million jobs in the leisure and hospitality sector at risk, with travel crashes and cancellations expected to continue. Moody’s Analytics, a rating agency, stated that more than half of the jobs in the United States which is about 80 million may be in jeopardy.

The virus is also taking its toll on health facilities and infrastructures across the globe. Italy is currently the largest affected country with a number of deaths surpassing China, since the outbreak of coronavirus. Across northern Italy, the virus has pushed the country’s National Health Service to a breaking point, emphasizing the test that other countries, especially developing and low-income countries, might face in their approach to contain the virus spread. Most hospitals and health facilities that could not handle the hazards are resulting to operating below their capacity by taking a few regular health-related cases or shutting down. What could be more devastating is the fact that the economic pains that accompanied the virus might not go away soon as envisaged.

The conventional policy measures currently being taken such as reducing interest rates and costs of borrowing, tax cuts and tax holidays are quite remarkable. However, these conventional policy measures are quite potent when there are demand shocks. There are limitations to the successes that can be recorded when demand shocks are combined with supply shocks. It is already apparent from the emergence of the current crisis that there are implications on the economy from both the demand and supply sides. Some of the demand factors include social distancing with consumers staying at home, limitations in spending and declining consumptions. On the supply side, factories are shutting down or cutting down production and output, while in other instances, staff work from home to limit physical contact.

The decision to close educational institutions and schools around the globe in an attempt to contain the pandemic has also led to a soaring number of children, youth and adults not attending schools. According to UNESCO Monitoring report on COVID-19 educational disruption and response, the impact of school closures in the over 100 countries that have implemented the decisions around the world has impacted over half of the global students’ population. These educational disruptions are being escalated particularly for the most vulnerable members of society.

Bracing up for COVID-19 consequences on the Nigerian economy

For most developing economies, the odds of sliding into a downturn are gradually expected as the global coronavirus outbreak puts severe pressure on the economy. For Nigeria, the country is still sluggishly grappling with recovery from the 2016 economic recession which was a fall out of global oil price crash and insufficient foreign exchange earnings to meet imports. In the spirit of economic recovery and growth sustainability, the Nigerian federal budget for the 2020 fiscal year was prepared with significant revenue expectations but with contestable realizations. The approved budget had projected revenue collections at N8.24 Trillion, an increase of about 20% from 2019 figure. The revenue assumptions are premised on increased global oil demand and stable market with oil price benchmark and oil output respectively at $57 per barrel and 2.18 Million Barrels Per Day.

The emergence of COVID-19 and its increasing incidence in Nigeria has called for drastic review and changes in the earlier revenue expectations and fiscal projections. Compared to events that led to recession in 2016, the current state of the global economy poses more difficulties ahead as the oil price is currently below US$30 with projections that it will dip further going by the price war among key players in the industry. Unfortunately, the nation has grossly underachieved in setting aside sufficient buffers for rainy days such as it faces in the coming days. In addressing these daunting economic challenges, the current considerations to revise the budget downward is inevitable. However, certain considerations that are expected in the review must not be left out. The assumptions and benchmarks must be based on realizable thresholds and estimates to ensure optimum budget performance, especially on the non-oil revenue components.

Furthermore, cutting expenditures must be done such that the already excluded group and vulnerable are not left to bear the brunt of the economic contraction. The economic and growth recovery program which has the aim of increasing social inclusion by creating jobs and providing support for the poorest and most vulnerable members of society through investments in social programs and providing social amenities will no doubt suffers some setbacks. Besides, the downward review of the budget and contractions in public spending could be devastating on poverty and unemployment. The last unemployment report released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) ranks Nigeria 21st among 181 countries with an unemployment rate of about 23.1%. The country has also been rated as the poverty capital of the world with an estimated 87 million people living on less than $2 a day threshold.

The decision to cut the retail price of gasoline under a price modulation arrangement is a welcome development. The cut is expected to curb rising inflation, especially food price inflation which will mainly benefit the poor. However, rather than the price capping regime introduced, by which it is expected of the Petroleum Products Price Regulation Agency (PPPRA) to constantly issues monthly guide on appropriate pricing regime. It is expected that the government will use this opportunity to completely deregulate the petroleum industry in line with existing suggestions and reports. In the event that the global economy becomes healthier and crude oil prices increases, the government might return to the under-recovery of the oil price shortfall by the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC). A policy that annually costs the government huge revenue and recurring losses to the NNPC.

Basically, the

Nigerian government essentially must lead economic diversification drive. It is

one practicable way to saddle through the current economic uncertainties and instabilities.

What the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic should further offer the Nigerian

economic managers and policymakers, is that the one-tracked, monolithic reliance

on oil is failing. Diversification priorities to alternative sectors such as

agriculture, solid minerals, manufacturing and services sectors, should be

further intensified.

[1] These figures were recorded as a 24th March, 2020.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has taken steps to ensure financial stability amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The steps include a reduction of interest rates for all CBN interventions from 9% to 5%, the creation of a N50 billion credit facility for households and SMEs impacted by the pandemic, and N100 billion in credit support to the healthcare industry3. Other policy actions were aimed at maintaining funding levels within deposit money banks in order to sustain lending capacity to the private sector. Overall, the CBN has committed over N1 trillion to support all critical sectors, which could help buffer the effect of a global recession4. While the fiscal stimulus package is in line with global best practice, it is critical to ensure that these interventions are not exploited. For instance, prospective beneficiaries may misconstrue these loans as grants; or may be unable to repay the loans leading to an enormous bad debt burden on the government. In addition, the extent to which these loans will reach certain businesses affected by the stay-at-home policy such as food vendors and artisans is debatable. However, MSMEs can utilize these interventions to boost local manufacturing and achieve import substitution in these industries.