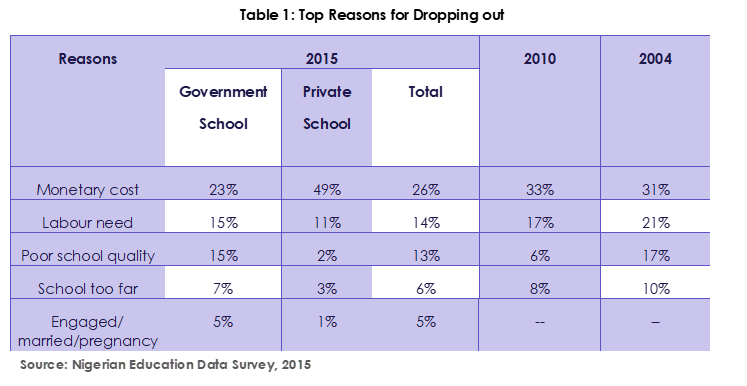

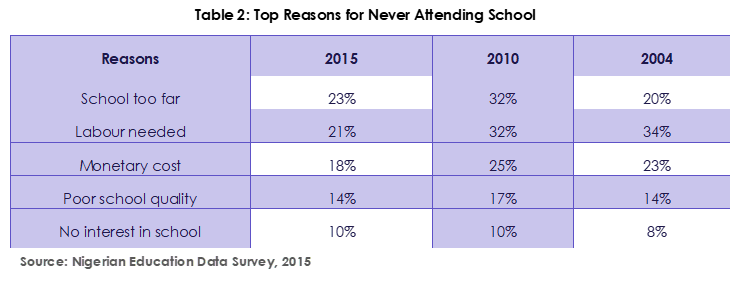

In 2003, Universal Basic Education (UBE) programme was launched to provide free and compulsory education from primary to junior secondary school. More than 15years since the inception of UBE, it remains curious that many cases of out-of-school children (OOSC) are still been attributed to monetary costs. For instance, the National Education Data Surveys (NEDS, 2015) indicate that 26% (23% public school and 49% private school) of children that stopped attending school in 2015 attributed it to monetary costs and this has consistently been the top reason for dropping out of school since 2004 (See Table 1). Similarly, Table 2 shows that 18% of children of school age not enrolled at all alluded it to monetary costs, which is the third highest reason after distance to school and labour needs of households. However, analysis of the reasons for exclusion as we did below suggests element of costs cut across most of these factors.

What are the Costs of Education?

From an economic angle, three types of costs are incurred in the process of schooling. First is the direct costs, such as expenses explicitly incurred on educational activities. These include tuition fees, feeding, uniform, transportation, books among others. Second, there are institutional costs that encompass recurrent costs (salaries, teaching aids, utilities, maintenance and repairs) and capital costs (land, buildings, furniture, equipment). The last category is the indirect costs, which is the opportunity costs of time spent by teachers and students in the process of schooling. The indirect costs is in principle, what would have been earned if not in school. It is, therefore, more relevant in evaluating decision on the cost-effectiveness of schooling.

In the private school setting, the direct and institutional costs are tied together and parents are expected to fully bear the costs. For public schools, how much government pays depends on the education policy in place. In Nigeria, the free education policy as stated in the UBE Acts (2004) only covers institutional costs plus tuition fees and to some extent, feeding and books. It, therefore, means that parents are expected to bear some costs despite education being claimed to be free. In simple terms, what is free under basic education in Nigeria is the costs incurred once a child reaches the door of the school. It is also important to note that a rational economic agent will invest time or resources in schooling only when the perceived benefit is at least equal to the costs.

Institutional and Direct Costs: How they affect school access

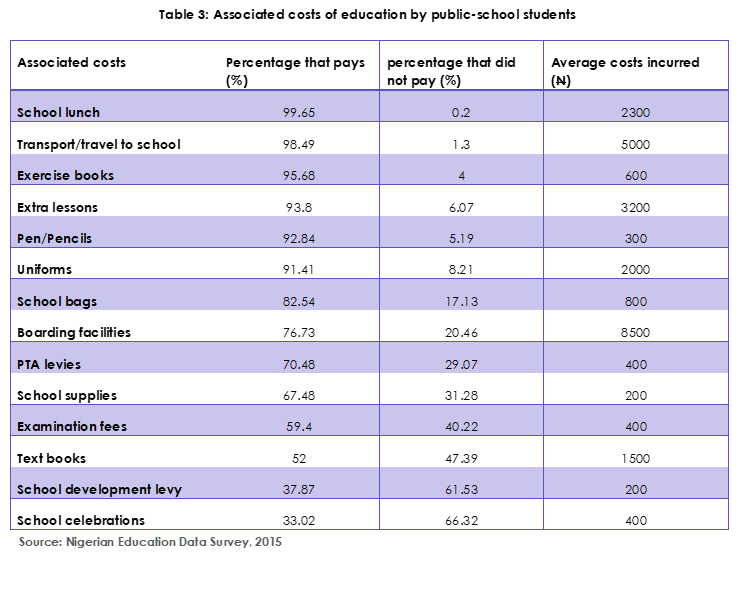

Given that the government does not fully cover the direct costs, parents bear a proportion of the costs of education. Although contributions from parents are expected to be small, this can still present a significant burden depending on households’ income level. Some of the costs reportedly paid by pupils in public schools in Nigeria are shown in Table 3. On average, these costs added up to N25800. For poor households that live below N700 a day, these associated costs amount to a significant burden to sending their children to school. Essentially, the associated costs of education is the monetary cost that parents were alluding to for children dropping out or not attending school at all.

Further dissection of the costs paid in public schools in Nigeria reveals another dynamics at play. Government has not been sufficiently funding the institutional and direct costs components as promised in the UBE Act. Some of the reported expenses are for items supposedly cover under the free education programme. For example, school development levy, school supplies and to some extent textbook and exercise books are part of the institutional and indirect costs promised under the UBE Act. Invariably, school administrators are using various creative means to transfer the shortfall in government funding to parents.

Furthermore, poor funding could explain other reasons given for not attending or dropping out of school. For instance, 23% and 14% of those that dropped out and those enrolled in school respectively is due to poor school quality. An additional 14% and 13% of those that dropped out and those enrolled in school respectively are due to distance from school. The poor school quality and distance to school are emblematic of poor financing for institutional costs.

Indirect costs: How they affect school access?

When a child is sent to school, the household and society loss productive hours that could have been spent on adding to family income and invariably gross domestic product (GDP). However, the wage loss is counted as an investment since households and society benefited more in future through higher income and productive labour force.

However, all this rests on the assumption that households are well informed about the benefits of education. In many instances, this is not the case. The second top reason for children dropping out of school (15%) and for those not enrolling (21%) is due to the early transition to the labour market. According to UNESCO (2014), 24.7% of child labourers aged 7-14years in Nigeria are out of school.

The overall trend suggests that many families consider the indirect costs to be very high, and prefer early entrance into the labour market. For instance, the Nomadic group that accounts for almost half the population of the OOSC in Nigeria- It has been observed that children from this group enter early into the labour market to support family business as herdsmen. In essence, indirect costs is arguably the single largest contributor to OOSC problem in Nigeria.

In general, while there seems a multitude of reasons for OOSC problem, our analysis indicates majority of the factors still boil down to costs of education. If direct, institutional and indirect costs, are not sufficiently catered for, it will translate to more population of OOSC and a future demographic burden to the country.