With the recent release of the 2018/2019 Harmonized Nigeria Living Standard Survey (HNLS), the true scale and scope of poverty in Nigeria will become clearer. When the World Data Lab’s Poverty Clock in 2018 released its poverty estimate which put Nigerian as the country with most extremely poor people, the federal government through the ministry of National Planning and Budget dismissed it saying ‘the National Bureau of Statistics is the statutory agency of government with responsibility for producing Nigeria’s official statistics, including poverty estimates.’ Finally, NBS-own estimate shows 82.9 million Nigeria, 40.1% of the population, live on less than ₦376.52 per day. This officially confirms Nigeria as the poverty capital of the world. Here are other notable highlights from the newly released poverty figure.

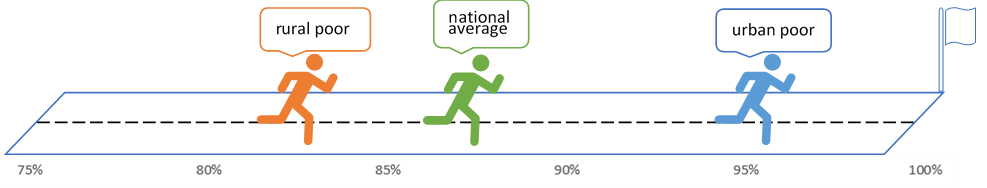

Poverty resides in rural areas in Nigeria. You are 65% more likely to be poor if you reside in a rural area. In addition, rural dwellers are farther below the poverty line relative to urban dweller (Figure 1). This means that the average urban poor person requires a smaller improvement in their consumption to cross the poverty line relative to rural dwellers. Specifically, the rural poor will require almost a threefold increase in their consumption just to be on par with the urban poor.

Figure 1: Depicting the poverty gap

Distinguishing those who are just a little away from the poverty line and those who are significantly away from the line.

Poverty does not obey federal character. Northern states have higher rates of poverty relative to Southern states. The poverty estimates from some states are worth highlighting. Sokoto state has the highest poverty rate in Nigeria at 87.73%. Lagos state has the lowest poverty rate in Nigeria. This seems not to be mainly driven by level of urbanization as Abuja, one of the major urban centers in Nigeria, has a poverty rate that is over 8 times that of Lagos.

Male headed households turn out to be consistently poorer than female headed households. Across all levels of disaggregation available in the preliminary report published by the NBS, female headed households tend to have lower poverty rates. Is there a selection issue with more empowered women heading the female headed household on average? We would have to wait for the complete dataset to study the mechanisms through which households’ outcomes differs based on the head’s sex.

Having at least a secondary education tends to beat living in an urban area without similar qualification in reducing the likelihood of living in poverty. Again, this observation is from simple descriptive analysis. The relative impact of education and residence on the likelihood of living in poverty will require more rigorous causal inference.

Smaller households are less likely to be poor relative to larger families. In fact, two out of three household with more than nine members turn out to be living in poverty. Conversely, only about one in five of the households with less than five members are considered poor.

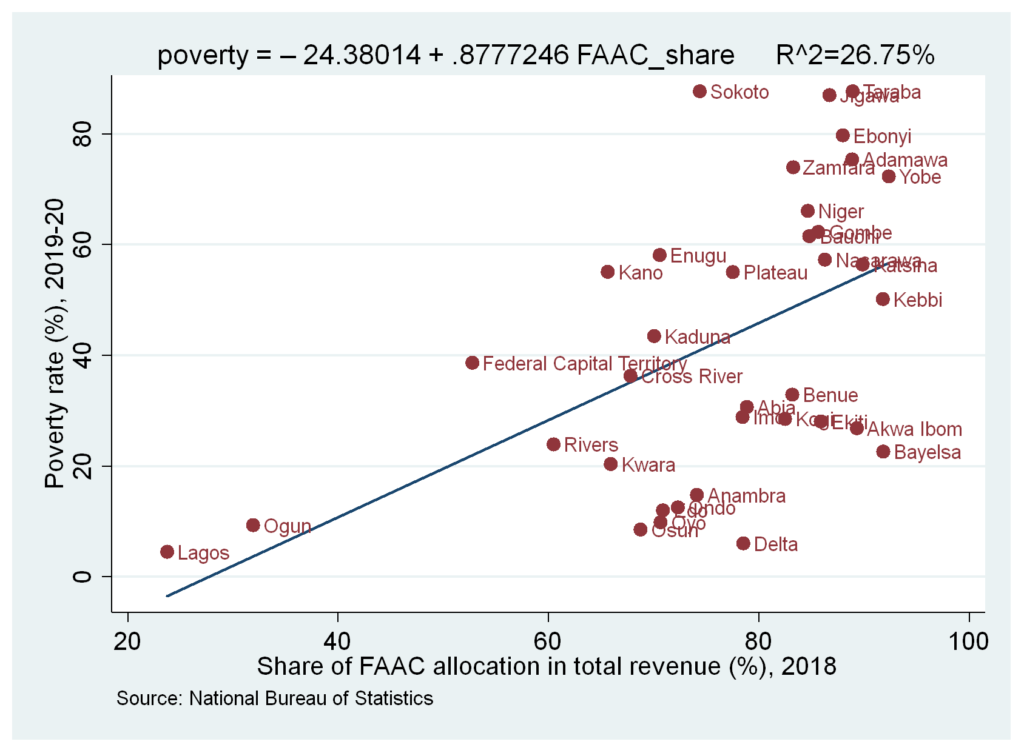

Poverty is higher in revenue-dependent states. States that rely on Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) allocations as their major source of revenues tend to have higher poverty (Figure 2). Lower internally generated revenue (IGR) signals low levels of economic activities within a state as well as weak state capacity. None of the nine oil producing states recorded a poverty rate of up to 31%, again underscoring the importance of state capacity.

Figure 2: Higher poverty in revenue-dependent states

What to make of the numbers?

The preceding analysis is based on descriptive summaries provided by the NBS. A full report and accompanying micro dataset, which should be published soon, will provide better opportunity for generating clearer insights. However, the following recommendations follow from the preliminary analysis.

- The rural-urban divide in poverty rates signals that poverty can be reduced by either developing the rural areas into urban centres or encouraging rural-urban migration. The latter seems like a less daunting task to undertake in the short term. However, a more enduring solution lies in development of a comprehensive rural development programme that effectively link economic transformation between rural and urban areas. Low hanging fruits such as improving the availability of agricultural inputs and infusing productivity-enhancing farming practices through extension workers can work wonders for Nigeria’s food security, nutrition, and rural poverty reduction.

- Educate rural girls! Only 10.15% of female headed rural households with post-secondary education live in poverty compared to 31.2% of male headed households with similar qualification. This pattern is observed throughout the data, signalling the impact of education on households’ outcomes. If you are looking for an intervention that can produce massive multidimensional impacts, you do not need to look beyond girl child education.

- Promote family planning and encourage smaller household sizes. The preceding analysis indicates that larger household sizes are a good predictor of poverty in Nigeria even if we may be led to believe that things get ‘cheaper by the dozen’. Promoting family planning should be an integral part of the government’s poverty reduction strategy.

- Make it easier for MSMEs to operate. A list of recommendations for improving development outcomes in Nigeria will not be complete without stressing the need to improve the conditions within which businesses operate. So, plug the normal trope about power, credit, other infrastructure, etc. here yourself.

This article was written by Joseph Ishaku and Adedeji Adeniran