Covid-19: Opportunity for reflecting on prospects for inclusive growth in Nigeria

There is huge uncertainty regarding the extent to which the current coronavirus pandemic would impact globalization and economic growth in the near future. Some experts have predicted an initial decline in international trade and economic integration, and subsequent improvement upon recovery from the pandemic, as seen in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. While others foresee a complete overhaul of how the global market system works, with a greater focus on national self-sufficiency. Regardless of the consequences, the present situation provides an opportunity for reflection, and proactive planning for the future of the Nigerian economy. It is imperative for the national economic management team and relevant stakeholders, to assess how globalization has fared in Nigeria especially in relation to inequality, and what can be done going forward, to promote sustainable and inclusive growth.

Globalization, economic growth and inequality in Nigeria

Adoption of neoliberal or free market policies in Nigeria can be traced to the Structural Adjustment Programs of 1986 imposed by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, as pre-conditions for loans. These policies included deregulation of the interest rate and foreign exchange system, privatization of state owned enterprises, elimination of import tariffs, and so on. All of these measures were put in place to enhance globalization in Nigeria, through increased integration into the global economy to encourage free flow of goods, services and capital across international borders and to attract foreign direct investment.

Nigeria has recorded consistent increase in pace towards globalization and embraced more liberalization polices over the last three decades, with more internationalization into global economic system. In determining the relationship between globalization, economic growth and inequality in Nigeria, it is important to understand the channels through which globalization interacts with distribution of opportunities and resources within the country, in order to draw up appropriate policies that empower the poor to contribute and benefit from increased shared prosperity.

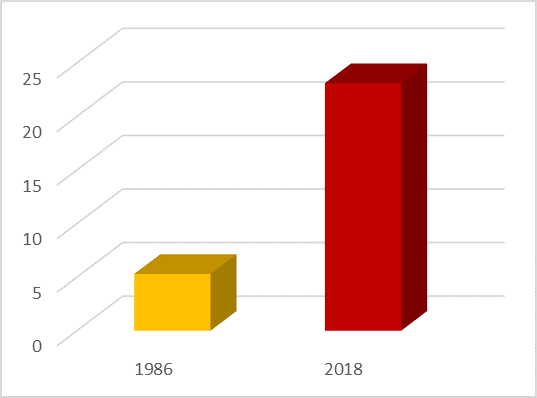

The discovery of crude oil in Nigeria caused an economic shift from agriculture to dependence on oil, resulting in Dutch disease syndrome whereby other sectors of the economy suffered because of increased international trade in oil and gas. Oil and gas production is capital-intensive and makes use of imported advanced technologies with minimal high skilled labour. Therefore, despite Nigeria having abundant supply of labour, expansion of trading activities in the oil sector has not necessarily translated to increased demand for labour. In addition, the crippling of the local agro-allied and manufacturing sectors has led to gross unemployment for unskilled/semi-skilled workers and higher premium on skilled labour, thus expanding the wage gap between the formal and informal sectors of the economy. Figure 1 shows a significant spike in unemployment rate since the liberalization policies commenced, rising from 5.3% in 1986 to 23.1% in 2018.

Fig. 1: Unemployment rate – Authors elaboration (National Bureau of Statistics, 2018)

Asides changes in demand and supply of labour, the Nigerian economy has become susceptible to fluctuations in the global oil market, often experiencing unfavourable terms of trade such that net exports are unable to cover imports. The lull in non-oil exports has also worsened, and can be attributed to a flawed national framework and weak institutions. Consequently, imports generally tend to be cheaper than made-in-Nigeria goods and services, thereby fueling failure of local small and medium enterprises (SMEs). This in turn reduces available jobs for low-income earners and ultimately, heightens the risk of transient poverty. Other channels through which globalization, growth and inequalities interact include; market concentration brought about by economies of scale, high entry costs, and non-tariff related entry barriers such as product or service requirements. All of these restrict market access and growth opportunities available to Nigerian SMEs, further widening income inequality gap among citizens.

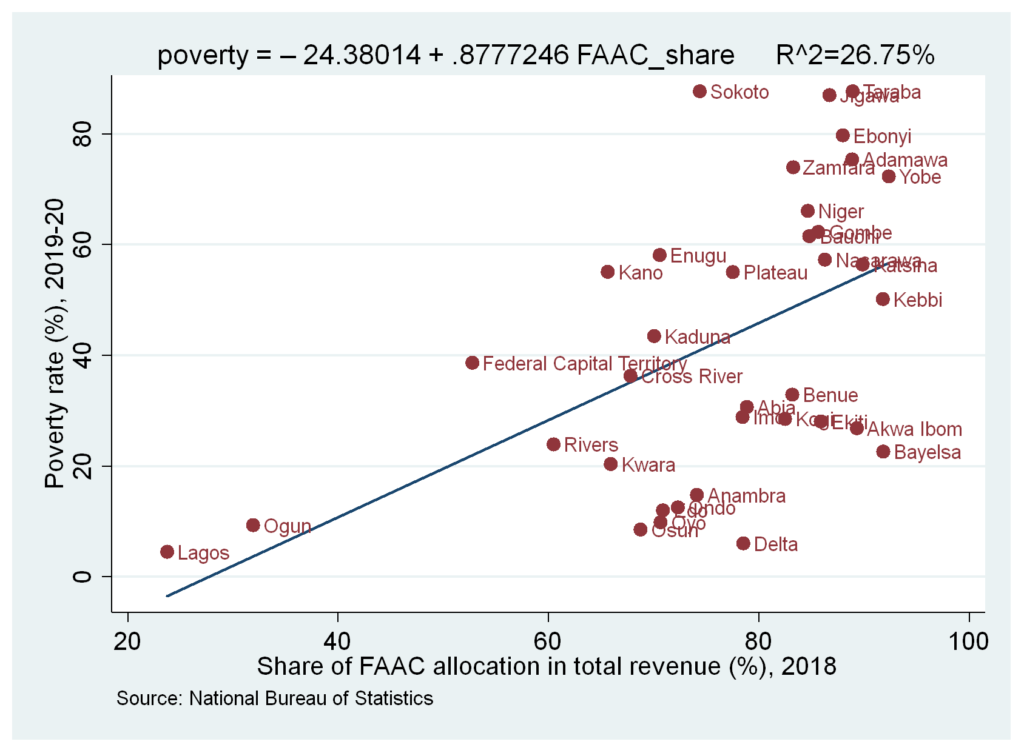

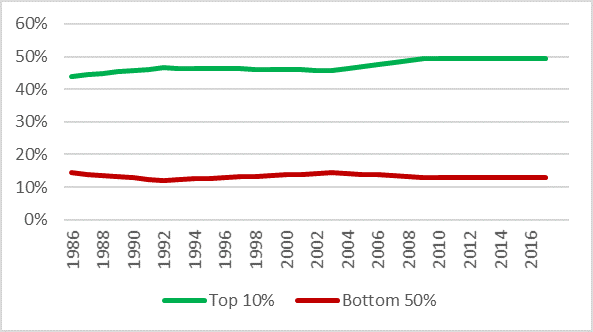

In addition, increased deregulation and privatization have resulted in reduced state spending on social goods and services, thereby limiting access and affordability for the poor. Although the country has recorded relatively stable growth for an extended period, this has not translated into shared prosperity. The WorldInequalityDatabase (Figure 2) shows that the proportion of national income accruing to the top 10% of the country’s population is currently more than triple the proportion accruing to the bottom 50% of the population, with no improvement in this trend for the last two decades. Asides income inequality, other dimensions of exclusion are prevalent in Nigeria. This growing divide has the potential to undermine national stability and development. Therefore, the country is faced with the challenge of recovering from the effects of the global pandemic, and ensuring that going forward; growth brought about by increased global integration translates into equal economic opportunities for Nigerians.

Fig. 2: Share of national income – Authors elaboration (WID, 2019)

By inference, Nigeria appears to have embraced globalization prematurely, evidenced by its weak institutions, poor human capital development, unsophisticated entrepreneurship, inadequate technologies and low financial assets. This has prevented its human and capital assets from competing favourably on the global stage. Thus, only a few already privileged citizens are able to enjoy the gains of globalization, by creating monopolies in certain sectors. Consequently, reform strategies to improve efficiency and capacity of local institutions, labour and capital assets are required.

Rethinking liberalization policy in Nigeria

Globalization can be valuable for emerging markets like Nigeria, when the right institutions are in place. Therefore, Nigeria needs to build strong and resilient institutions to provide a platform for driving innovative policies geared towards diversifying the economy, building capacity and a conducive environment for business growth, while considering the impact on marginalized groups. Export promotion strategies should identify priority sectors based on potential to create jobs, boost export earnings, and have robust market linkages. Policies on port reforms, simplification of export procedures, stable exchange rate, and indigenous technology advancement should be implemented. E-commerce should also be encouraged due to its potential for levelling the playing field between small and large firms in global markets. In addition, hindrances to business growth must be fixed, for example; power supply, distribution networks, and access to finance, with extra emphasis on rural communities.

Human capital and enterprise development are also a critical factor for inclusiveness, in terms of policies that improve affordability, availability and effectiveness of education and skills acquisition programs. This has the potential of boosting labour productivity, creating more opportunities for labour mobility and increased wages for low-income earners. In order to achieve this, it may be necessary to realign budgetary allocation to the education sector to expand access for disadvantaged groups. Finally, it is imperative to revisit existing redistributive policies, to ensure social protection programs adequately cater for marginalized individuals, and that the tax system is efficiently progressive and capable of promoting shared gains from national growth. Also, it is necessary to put in place measures to curb illicit capital flight and tax evasion by multinational corporations operating in Nigeria as these could play an important role in reducing inequality of outcomes within the country.

This article was written by Sone Osakwe, Research Intern at CSEA

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China