The dawn of the COVID-19 pandemic affected the globe with its far-reaching impacts. Even though the long-term health, economic, and social impact is still indeterminate, the immediate effects have ensued with significant loss of lives and livelihoods. Those already living in poor and vulnerable conditions have been the hardest hit, suffering extreme hardship from reduction in income and decreased consumption, since existing coping mechanisms are grossly inadequate to counter the shocks from the pandemic. This scenario is bound to threaten their chances of survival, plunge them further into extreme poverty as well as expand the inequality gap. As a result, the importance of investing in efficient social protection programmes has never been more pronounced.

Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Africa have been particularly vulnerable to the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, with demand for their products and services declining since the outbreak in late 2019. A recent African Union report that surveyed African SMEs about COVID-19’s impact on their businesses reported that the pandemic had heavily impacted 93% of businesses, while 95% of them did not receive any form of government support to cushion the impacts of the economic downturn. In a survey of MSMEs in Nigeria by the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa (CSEA), 69% of respondents said the pandemic had significantly affected their access to finance, capital and financial liquidity. Total direct output loss accruing to Nigerian MSMEs in the year 2020 was estimated at about NGN5.8 trillion (U$D 14.85 billion).

At the same time, the COVID-19 crisis has accelerated the adoption of digital technologies across the world. The lockdown restrictions created a rare opportunity for many MSMEs and households to engage with digital technologies, allowing businesses to stay operational and access new markets. Unfortunately, given the enormous digital divide in terms of skills and infrastructure, the benefits of this digitalisation have been unevenly distributed.

MSMEs play an essential role in the overall growth of the industrial economy of Africa. They constitute about 95% of African businesses and contribute 80% of regional employment. Therefore, they are a vital industry for inclusive socio-economic development. The rapid migration to digital technologies as a result of COVID-19 has continued into the recovery phase in Africa, and augmenting MSMEs’ capacity and ability to keep pace with the new digital expectations that have emerged will be critical to driving COVID-19 recovery on the continent. However, only a few MSMEs capable of navigating and integrating into digital platforms may survive the prolonged effects of the crisis. Many firms are not capable of embracing digital initiatives, particularly in the informal sector. Differences in technological, social and networking capabilities further exacerbate the digital divide.

Digitalisation’s potential contributions to MSME survival include wider customer reach, cost reduction, and opportunities to optimise products, sales and revenue. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram are now being used to interface directly with customers and effectively acquire new ones. MSMEs should efficiently market their products and services for social media platforms, which have an estimated user base of over two billion users, while reducing traditional overhead costs and technically reducing the distance between MSMEs and their customers. MSMEs can also leverage digital innovations for survival by restructuring their enterprise towards remote working, migrating to e-commerce and reorganising their production lines towards goods and services with higher demand.

Beyond COVID-19, however, digitalisation provides the opportunity for MSMEs to leverage the benefits of the recently implemented African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Symbiotically, the AfCFTA delivers a channel for the region's fragmented countries to band together to seek alternative paths to development by harnessing combined strengths and resources to support digitalisation.

"There is a concern about whether the AfCFTA will ensure an equitable spread of digitalisation gains. This will depend on how it responds to competition, antitrust and cross border taxation arising from the digital economy."

While more than 500 million Africans (39% of the total population) are connected to the internet, the spread and scope of digitalisation have not translated to economic development and structural transformation on the continent. One reason for this is the small economic size of many African countries and their fragmented nature. Individually, most African countries lack the economies of scale and investment capacity needed to drive down costs and mobilise mass adoption. This also partly explains the weak and uneven development of domestic digital platforms in Africa. Regional integration can alleviate these problems by promoting investment in aids to trade, of which digital technology is a key component. With the AfCFTA, the continent becomes a single market, thereby diminishing economic size and fragmentation issues.

Regional integration also has the potential to resolve another constraint to widespread digitalisation in Africa: citizens’ weariness of the potential abuse of digital platforms for surveillance and restrictions on their constitutional rights. Given the role social media played in the Arab Spring, there have been many attempts by African states to shut down the internet or control access to the digital space in response to protests or dissent. In 2019, about 25 cases of partial or total internet shutdowns were documented in Africa, representing a 47% increase from 2018. Given this trend, expansion in digital footprints like digital identification systems and facial recognition has faced scepticisms and outright rejection from citizens and civil society. Regional integration can help in this regard. The uniform data governance that is likely to ensue within the free trade area will separate business cases for digitalisation from the political ones. Moreover, regional integration will make it economically costly for states to arbitrarily shut down the internet, as this will have broader continental effects.

However, for the benefits of AfCFTA to accrue inclusively, it is essential to narrow the uneven development of digitalisation in Africa. Some of the recent growth in domestic digital platforms in African has been concentrated in a few relatively rich countries like Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya. Therefore, there is a concern about whether the AfCFTA will ensure an equitable spread of digitalisation gains. This will depend on how it responds to competition, antitrust and cross border taxation arising from the digital economy.

National governments at both the federal and state level can enhance the digital capabilities of MSMEs by promoting programs that facilitate the adoption and use of digital technologies. Governments, the private sector and the civil society need to collaborate and facilitate knowledge flows that contribute to building and strengthening a systemic digital change. The first steps would be to identify the gaps that hinder digital take-up and provide context-specific solutions that bridge the identified gaps. While the priority of crucial challenges will differ by country, the following policy measures must be pursued cross-nationally:

● Digital skills training: Digital literacy skills are fundamental to achieving digitalisation. There needs to be an intentional effort to prepare current and future business owners to succeed in this changing landscape. This includes training that provides MSMEs with a holistic understanding of digitalisation and equips them to actively and fully engage in it. Particular attention should also be paid to tailoring programs to the needs of women and girls.

● Provide infrastructural support: It will be critical to promote technology-enabled interventions that facilitate access to mobile phones, tablets and computers that enable MSMEs to adopt and access digitalisation. Policymakers will need to back this up with complementary investments in physical infrastructures, such as improved electricity supply and support for software development and assembly of ICT equipment and accessories. It is also imperative to extend improved internet connectivity to rural areas and underserved population.

● Reduced cost of digitalisation: Many businesses are already faced with devastating financial consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. As MSMEs will incur expenses as they digitally transform their businesses, they should be encouraged and incentivised to start with low-cost pilots and little resources that can be scaled up. A recent survey of 45 African countries shows that only 10 countries meet the standard of affordable internet, defined as paying 2% or less than the average monthly income for 1 gigabyte (GB) of data. It is critical to align the costs of digitalisation with the ability of Africans to afford it. Such a reduction in the costs of digitalisation could come through crisis-response partnerships with telecommunications providers. For example, lower data costs could encourage MSMEs to participate in online digital literacy and migrate to e-commerce. Other African countries should embrace the success models of Kenya and Nigeria. Through the internet exchange gateway, the Kenya Internet exchange points (KIXP) grew from carrying peak traffic of 1 Gigabit per second (Gbps) in 2012 to 19 Gbps in 2020. The Internet Exchange Point of Nigeria (IXPN) grew from carrying 300 Megabits per second (Mbps) to peak traffic of 125 Gbps in 2020, bringing a cost savings of US$ 40 million per year.

● Improve Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): It is imperative to strengthen public-private partnerships, particularly in the financial and telecommunications sectors, in delivering the needed interventions. Governments and private technology firms could pull resources and technical know-how to make internet data and ICT facilities affordable, which could be a cornerstone for MSMEs to adopt and utilise digitalisation. Such public-private partnerships hold the key to the future development of MSMEs by enhancing digital literacy among MSMEs, reskilling and upskilling their potentials to compete effectively in AfCFTA. Morocco has exhibited an excellent PPP model for digital transformation through its 2020 Digital Strategy, prioritising the development of e-government services.

Digitalisation can support African MSMEs to emerge from the COVID-19 crisis stronger with an unparalleled global competitive advantage when adopted and applied efficiently through the AfCFTA. Therefore, it is time for governments and policymakers to prioritise long-overdue reforms in African business regulations, skills development schemes and public sector governance.

This article was first published on the African Portal

Tariff reform is often listed as a high-priority issue in Nigeria. In March 2020, the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) issued an order to transition from demand-based to cost-reflective and service-reflective tariffs. Consumers are now supposed to pay based on how long they receive electricity daily, divided into groups commensurate with the quality of services offered. After several delays due to COVID-19, this change finally took effect in September 2020.

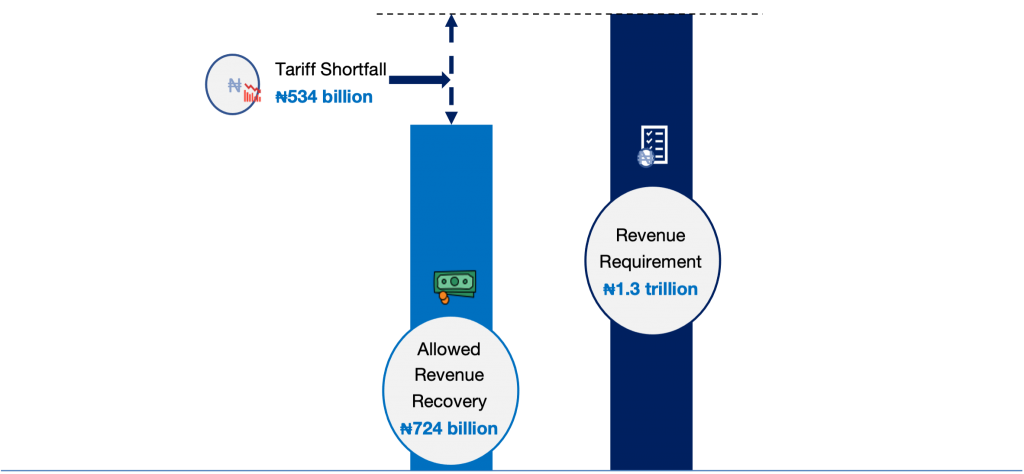

FIGURE 1: Projected Revenue Requirement, Allowed Revenue Recovery and Tariff Shortfall in 2020 (Data was sourced from NERC, 2020).

TABLE 1: The new service-reflective tariff bands (Data sourced from NERC, 2020).

| TARIFF BAND | ELECTRICITY SUPPLY (HOURS PER DAY) | TARIFF REVIEW |

|---|---|---|

| A | Minimum of 20 hours | Highest tariff band |

| B | Minimum of 16 hours | Second highest tariff band |

| C | Minimum of 12 hours | Moderate tariff increase |

| D | Minimum of 8 hours | No tariff increase |

| E | Minimum of 4 hours | No tariff increase |

This article was first Published at Energy for Growth Hub

The Mambilla Hydropower project will be a complex of four dams and two underground stations in the eastern Nigerian state of Taraba. The Chinese Export-Import Bank is funding 85% of the US$4.8 billion cost, and when completed, the dam will be Nigeria’s largest power plant at 3,050MW. The project, in development for 55 years, is expected to be commissioned in 2027 if construction begins this year.

Key risk factors include:

Besides creating thousands of jobs directly, and enabling the growth of many more through more reliable energy services, Mambilla will have a number of additional benefits:

The Mambilla project is currently conducting site surveys, sensitization, enumeration, skill acquisition, capacity building programs, and preparation for compensating affected groups. The federal government just attributed N425 million of the 2021 budget for Mambilla’s construction, upholding its commitment to contribute 15% (US$870 million) of the cost.

Despite Mambilla’s current progress and government funding, it remains to be seen if it will be completed by the seven-year projection, as access to budgeted finance as well as a possible change in administration in 2023 poses significant risks to slow construction.

This article was first published at Energy for growth hub

On January 1, 2021, the long-anticipated African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) became a reality. The benefits of creating a single African market under the AfCFTA are wide-ranging and potentially revolutionary. By reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers to intra-African trade, the initiative could boost regional exports by 29 percent and income by 7 percent between 2020 and 2035. There is also optimism that greater access to a larger market base could reduce production costs and lead to greater economies of scale for local producers and exporters.

But AfCFTA’s potential might not be fully realized without stronger digital connectivity and effective policies that (1) promote the free flow of data and information across member states to facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration and (2) reduce trade integration costs and address existing structural barriers to intra-regional trade in Africa.

At the most basic level, AfCFTA is governed by five operational instruments (an online negotiating forum; a digital payment system; the monitoring and elimination of non-tariff barriers; the African Trade Observatory (ATO); and rules of origin), all of which require effective digital connectivity to be successful. More importantly, developing the continent’s digital sector is crucial for economic integration and could help address some long-standing structural trade barriers while ensuring that the gains arising from the AfCFTA are equitably shared. Examples of how strengthening the digital economy can break down these barriers include:

Despite the vast potential and importance of digitalization for regional integration, digital development remains low across Africa. The problem is notable in two crucial areas: digital penetration and data governance framework. The capacity to address these challenges will determine the AfCFTA’s success. We briefly highlight the critical issues along these areas.

Access to the internet remains limited in Africa, with 47 percent of the continent’s population able to access the internet, compared to a global average of 63 percent. The quality of digital infrastructure is also poor, with slower 2G still accounting for 59 percent of the available mobile technology generation mix and 4G penetration at just 6 percent of the mix. It is therefore unsurprising that most African countries are inadequately prepared to leverage the global digital revolution.

To gauge the implication of this on the AfCFTA, which is expected to be facilitated mainly through online transactions, we measure the correlation between an index of digital preparedness among African countries, and an index measuring the commitment and readiness for AfCFTA. Figure 1 suggests a positive relationship, which implies countries with weaker starting positions on the digital preparedness index are more likely to be left behind as benefits from the AfCFTA accrue to better-prepared countries.

Figure 1. Relationship between Digital Preparedness and Readiness for AfCFTA

Disruptions caused by COVID-19 have already highlighted the importance of better digital connectivity across AfCFTA members. The AfCFTA Phase II negotiations, which were forced online due to the pandemic, were slowed by connectivity problems and concerns about the security of online discussions. Given that governments continue to experience difficulties digitally connecting with one another, small and micro firms and households undoubtedly face more severe challenges.

Supporting greater cross-border economic activities on the continent will lead to increased cross-border data sharing. It also requires greater harmonization on how AfCFTA members govern the use of data and digital systems like payments and digital identity, and greater coordination on issues such as taxation of digital platforms and industrial policies aimed at supporting digital entrepreneurs.

Since trust is a prerequisite for ensuring uninterrupted cross-border digital interactions, a clear data governance structure at the national and regional levels is needed. Such laws are required to allay fears related to protection of citizen’s constitutional rights, including the rights to privacy, data protection, and freedom of speech.

There have been some initial steps: At a regional level, the African Union (AU) initiated a Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection in 2014. However, it is still pending ratification, as only eight countries have assented. More recently, the AU, alongside other development partners, developed a digital transformation strategy for the region. The strategy’s objective is to serve as a roadmap in harnessing digital technologies to promote a fully integrated and inclusive digital society by 2030, with the hope that it improves the welfare of Africa’s population. Since the strategy is relatively new, it is premature to assess its effectiveness. Despite these regional action plans and convention, a robust and coordinated regional data governance framework to ensure seamless data interoperability is lacking.

The United Nations Congress on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reports that a significant number of African economies have yet to enact legislation to safeguard digital transactions and data use (figure 2). And due to countries’ varying digital maturity levels, most African countries that have or are drafting data protection laws are adopting different rather than harmonized strategies, risking market fragmentation. Enforcement capacity, financial and human resources, and reliable institutions to support a well-functioning data governance environment are also lacking in most countries.

Figure 2. Number of African countries that have adopted digital protection-related legislation

Source: UNCTAD E-Commerce Legislation Index - April 2020

To increase the competitiveness of the African digital economy and maximize the potential of the AfCFTA, governments, non-state actors, and development institutions should collaborate to ensure the speedy implementation and enforcement of data governance policies and laws that guarantee trust, transparency and increase digital inclusiveness.

Beyond ensuring security of data flows, it has become extremely critical to build the soft and hard infrastructure for a well-positioned African digital economy, through expanded access to digital technologies, wider internet adoption, improved public expenditure on information communications technology infrastructure, and a more conducive regulatory environment for private sector investments in the sector. The African Development Bank’s Programme on Infrastructure Development for Africa (PIDA) is one vehicle to achieve this. However, it will require a stronger linkage to AfCFTA for better trade facilitation and a more supportive legal framework. This could be in form of providing guidelines on minimum standards, a shared pool of resources, and a timeframe for effecting harmonized interventions especially for countries that are lagging in growing their digital economy. Further, at the country level, digitalization must become a top development priority for governments, with necessary policy reforms and budgetary allocations to accelerate digitalization and deliver on shared prosperity that the AfCFTA promises.

This article was first published at Centre for Global Development