Effective Targeting of COVID-19 Aid in Nigeria

Faced with an invisible and novel enemy to fight, governments across the globe have deliberately shut down their economies and placed cities on lockdown in order to stem the spread of the COVID-19 virus. In Nigeria, two states and the federal capital territory, have so far enforced a total lockdown, while other control measures have been implemented in other states. These mitigation strategies, albeit necessary, have affected the livelihood of most citizens, especially those operating in the informal sector who rely on daily incomes for survival. The Federal Government has introduced various social protection policies to support vulnerable groups during the COVID-19 crises. These policies are primarily targeted towards the 2.6million households on the social registry for the vulnerable, and an additional 1 million households are to be provided conditional cash transfer for 2months.

The present social registry uses a three-stage targeting process based on geographical targeting, community-based validation, and proxy-means-testing (PMT) in order to identify the poorest of the poor in Nigeria. With over 90 million Nigerians living in extreme poverty, the social registry covers only about 2% of the poor, excluding many households given the enormous financial requirement for universal social protection. While the coronavirus lockdown will negatively affect most Nigerians, the impact will vary markedly across groups, even amongst the poor. There are legitimate questions about the suitability of the existing social registry as a reference for the groups most vulnerable to the economic shocks induced by the coronavirus lockdown.

For the COVID-19 social protection interventions to be effective in curbing severe drops in basic consumption (largely food and housing), they need to be well targeted to those most vulnerable to Covid-19 shocks. Those most likely to be affected by COVID-19 lockdown measures are not necessarily the most vulnerable groups nationwide, and are likely to be missing from the social registry used for the Federal Government’s social protection measures.

What is known about the current social protection registry is that it largely covers agricultural and rural households, especially those with human capacity constraints. However, these groups are also less likely to be negatively affected by the economic shocks induced by the lockdown for a number of reasons: First, they are largely isolated from the major economic centers, being primarily rural and agricultural, hence basic livelihoods remain minimally unaffected by the lockdown. Second, the transportation of food items is excluded from the lockdown, which means that rural farmers may continue to get their produce to markets. Third, and more important, most households in this group produce a majority of what they consume, and are therefore better able to maintain basic consumption levels during the lockdown.

In order to more effectively target groups of the poor that are most vulnerable to negative consumption shocks during the COVID-19 lockdown, we need to ask, in the most basic terms: which groups of people need to earn an income every day in order to purchase food? Put another way, poor households whose basic income and consumption patterns are more closely tied to the market would be most likely to be negatively affected by the lockdown. In this piece, we profile the characteristics of the groups that are most likely to be affected by the government lockdown and restriction of economic activities vis-à-vis those on the social registry, explain why COVID-19 social protection interventions ought to be better targeted to these groups, and suggest ways to improve poverty targeting for those affected by the coronavirus shock.

Using data from the Nigeria Demographic and Health surveys (2008 and 2013), we find that the urban poor is more likely to work in non-agricultural occupations, which often involves commuting between suburbs and satellite towns into the urban core. Here, we may think of drivers, cleaners, sales associates, and operators of micro-enterprises, etc. Incomes from these occupations that involve work in the city’s core are the most likely to be affected by the lockdown in economic activities. While most agricultural activities will slow down, the exception to food transportation, storage, and sales, means that income loss here will be minimized. Furthermore, data from the National Living Standards survey (2010) shows that 64% of the food consumed by the poor in rural areas comes from food that they produce themselves (auto-consumption), compared to just 22% for poor urban households. This implies that the urban poor is significantly more likely to experience a greater decrease in food consumption with a decrease in market income.

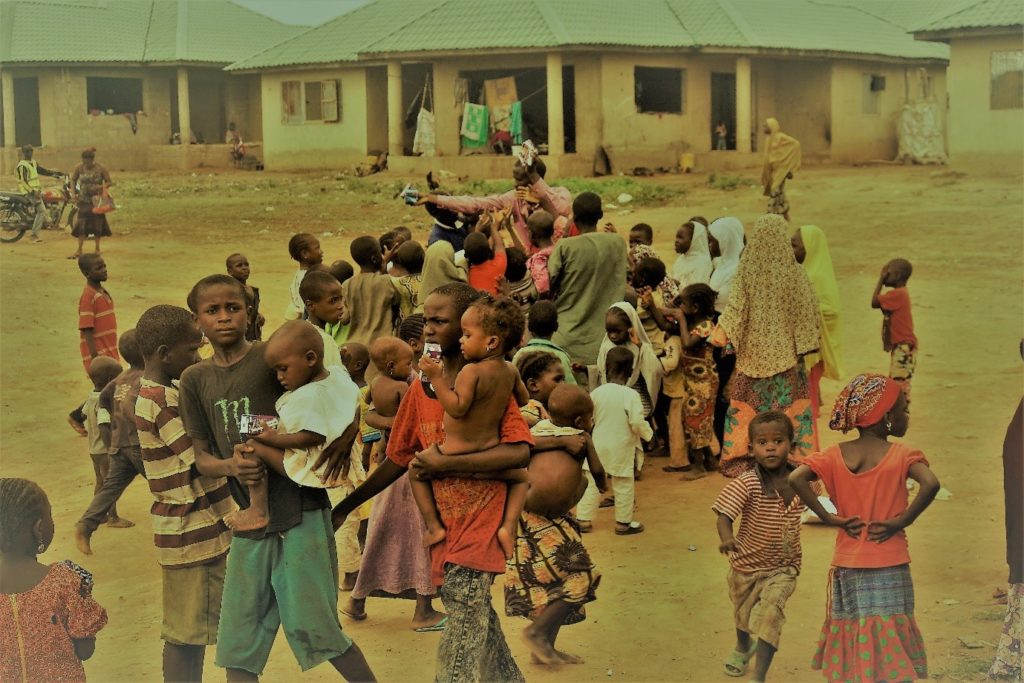

Overall, the data reveal that the urban poor are more likely to suffer a decline in incomes as a result of the economic lockdown introduced to control the spread of COVID-19. As a result, the urban poor is also substantially more likely to suffer a decrease in food and other consumption, because unlike rural households, they largely consume what they are able to buy from market incomes. The urban poor have their livelihoods more closely tied to the market, and with a market shutdown, they are better targets for supplementary incomes/consumption intended to alleviate the hardships induced by COVID-19. This category of the poor is largely underrepresented in the current social protection registry.

Alternative Targeting Mechanism for the Urban Poor

The preceding discussion highlighted the inadequacy of the present social register as the urban poor are not sufficiently captured. However, it is difficult or impossible to rebuild or update the social registry in the midst of the pandemic. The government will need to explore alternative targeting mechanisms in the immediate term. One key characteristic of the urban poor is that they mostly live in slums, which enables them to minimize rental costs in cities. Social security targeted at the slums and other geographical locations where the urban poor people reside will be crucial. The Government can also leverage on the social infrastructure and local knowledge of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that have worked with urban poor in the past. With proper accountability in place, non-state actors can assist in the identification of the vulnerable households and suggest other effective ways of reaching them. This suggests a combination of geographic targeting complemented by community identification.

The efficacy of targeting through direct deposit into individuals’ accounts using their unique Bank Verification Number (BVN) will be weak in the present circumstances. With 36.8% of the adult population in Nigeria still financially excluded, targeting only those with a low balance in their account will exclude the most vulnerable people, who are less likely to have a bank account, and might find it more difficult to get into a bank location where they are able to withdraw cash. Further, using the banking approach also means individuals rather than households will be targeted. Without a quality system for auditing to check duplication, using BVN alone is susceptible to abuse. In some households, multiple members might be able to take advantage of the palliatives at the expense of financially excluded households.

Irrespective of the mechanism adopted by the government, it is important to emphasize that apart from food security, adequate measures are required to prevent the spread of COVID-19 among urban poor. The optimal poverty targeting for the urban poor must, therefore, incorporate social distancing at its core.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China