COVID-19 in Nigeria – Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) as Vulnerable Populations at Risk

Here is what we know – COVID-19 has no known cure (at the time of writing this article). We also realize that given the dearth of medical infrastructure in Nigeria, a full-blown pandemic would pose a rather dangerous threat. On the bright side, the mechanism of the disease’s transmission is clear – we know that it happens primarily through close contact with carriers of the causal Coronavirus, either by imbibing virulent bodily fluids (mucus, sputum) from them aerially, or through tactile contact with virus-riddled surfaces. In light of all established knowledge, the primary defence against the spread of the pandemic has therefore been the enforcement of social distancing and self-isolation within affected and at-risk populations, to minimize contact between the infected and uninfected. Countries like China have achieved significant declines in rates of new infections, largely by this method.

What may not be very clear at this point however, is precisely how profound the Nigeria (COVID-19) disease-scenario is. In-country data on infected persons may very well not be completely accurate representations of reality, as tested persons so far have predominantly emerged from the upper end of the income divide – most probably for reasons of limited resources and low knowledge-access among populations at the other end. What is more, the vast majority of Nigerians exist on that poverty side of things, and live in impoverished physical conditions. These groups (who will almost certainly not present for testing, except when compelled to by personal crisis) are potentially a tinderbox for the exponential spread of the pandemic, given the unsanitary environments and lifestyles that their impoverishment reinforces, as well as the fact that the methodologies of social distancing and self-isolation are hardly feasible among their ranks. They are, in addition, significantly less able to access and utilize vital information regarding prevention and management of the disease (for reasons of education and resource-limitation). The point is this – the COVID-19 situation in Nigeria at this time is precarious (in terms of risk to life and health) – perhaps more so than is apparent – and this is largely because of that poverty-dimension. What is more, the current government response of enforced shutdown of economic and other activities within most-hit states ( shutdown will probably be effected in other states soon) will also deeply and adversely affect the livelihoods, and therefore, lives of the poor, whose incomes are often earned and exhausted on the same day.

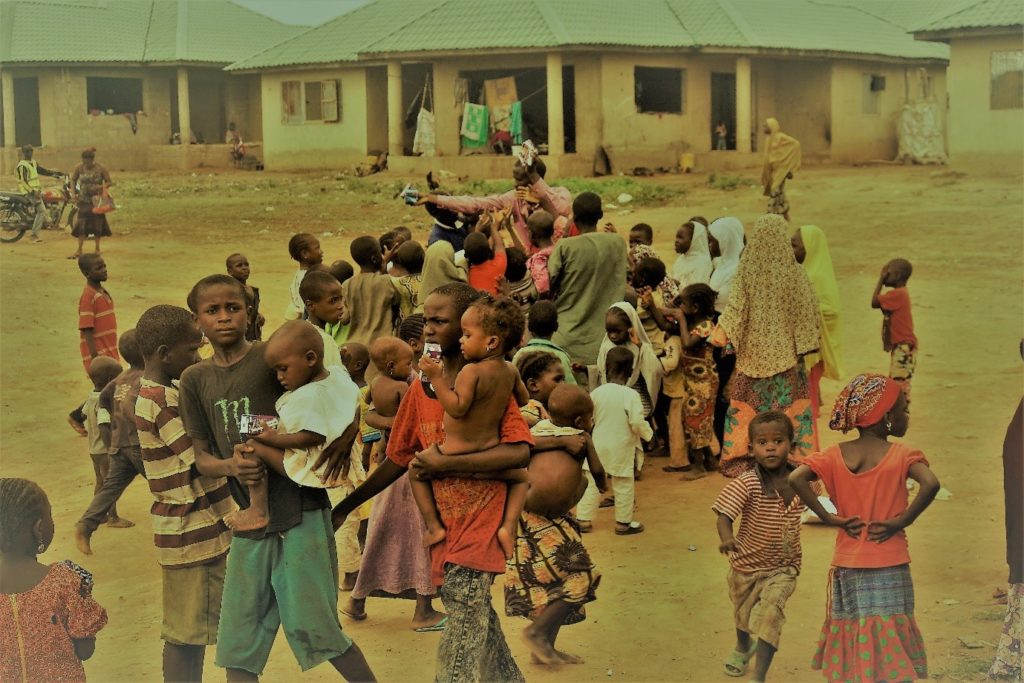

For these reasons, Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Nigeria are in very significant jeopardy. According to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR), over 2 million Nigerians have been displaced from (Boko Haram) insurgency hotspots in Northeast Nigeria since 2009. These migrants have settled into IDP Camps across the country, which are characterized for the most part by overcrowded populations amidst severe infrastructure deficits. IDP populations in Nigeria are dominated by poorly educated, rural, farm-folk, who are hardly able to achieve meaningful livelihoods in their new, mostly urban settlements. They are for this reason typically impoverished and dependent on humanitarian-aid for even their sustenance; and have very limited access to healthcare or water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) amenities as well. In the past, these terrible living conditions have rendered IDP camps a cesspool for dangerous medical crises – in 2017 for example, there were over 4,800 cases of Cholera and 61 deaths, in an outbreak across IDP Camps in Nigeria.

One can therefore see how this looming COVID-19 pandemic would give cause for grave concern regarding the level of risk their situation exposes Nigeria’s IDPs to – and further to that, how much risk they might pose to the larger population (could IDP settlements for instance inadvertently become repository-populations for the virus, and vehicles for its proliferation?). In the event that it is not immediately clear, here are some of the reasons for this concern:

WITH CHARACTERISTICALLY LIMITED LIVING-SPACES IN IDP CAMPS, SOCIAL DISTANCING AND SELF-ISOLATION WILL BE DIFFICULT TO ACHIEVE

The reality is that, with regard to how overcrowded they are, most IDP camps in Nigeria are unfit for a healthy living anyway. Typical camps consist of makeshift or poorly-built housing that hold multiple times the number of occupants that they should; while common areas and outdoor spaces, even amidst recent events, constantly have numerous people congregating within them. These IDP Camps are in essence, in the current climate, accidents waiting to happen.

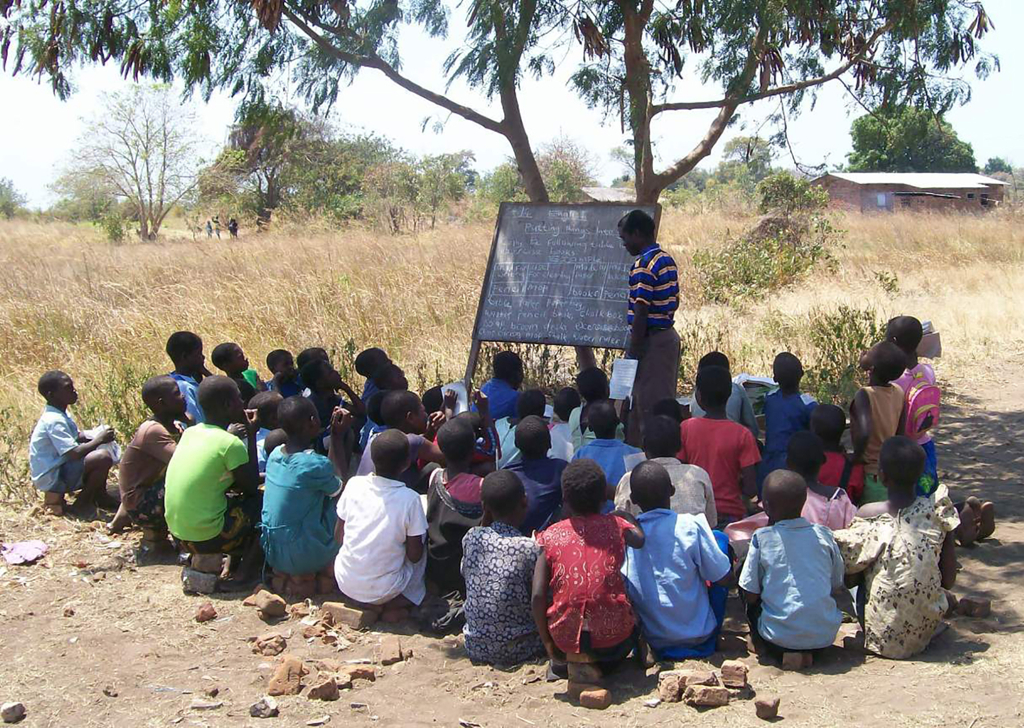

POOR INFORMATION-ACCESS AND LOW EDUCATION-LEVELS COULD HEIGHTEN SPREAD

Information and knowledge have proved formidable, and effective, weapons so far in the fight against the spread of COVID-19. Across the globe, we have seen and learned from other sources, accounts from different countries of how to successfully prevent incidence. Information of this sort might however not be fully appreciated by poorly educated persons such as IDPs, even when they can access it – for lack of proper comprehension of the situation. For instance, some Nigerians still had to be forcibly barred from gathering publicly only recently. This is an attitude that represents a potential to enable spread of the disease amidst measures to curb it. Until the time when observing the reality of the pandemic foists an understanding of the situation’s true gravity upon them, demographics such as the IDP, might function as loopholes for the propagation of COVID-19; in their disregard of safety conventions.

LIMITED ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE MIGHT CAUSE MULTIPLE TYPES OF ADVERSE OUTCOMES

If one envisages a scenario of panic where a great number of IDPs require urgent, life-saving medical care that is in short supply, it is easy to understand how things might escalate at that point. Caregivers to, and family of the dangerously ill (even the moderately ill themselves) might easily in that time succumb to a desperation in their actions, which would put everyone else at risk – in both health and civil terms.

TRUNCATION OF INCOME (FROM LOCKDOWNS) WILL AFFECT IDPs MORE THAN MOST

IDP populations typically have no means of cushioning a cessation of earnings, even for short periods. A situation such as the one that has been imposed in some places, and which portends in others – where all monetary inflow is stopped (during state-wide lockdowns) – simply holds the implication of potential starvation for IDP families. They will not survive without external help.

The state of things is deeply concerning all round, but there are measures that can be taken to forestall doom:

- Government, as well as humanitarian players, should scale up current response-plans, to cover vulnerable and at-risk populations such as IDPs in every foreseeable dimension during this pandemic – this means adequate healthcare for treatment and prevention, as well as food and other resources needed.

- Communication strategies should be formulated and enacted, which will effectively demonstrate the full dimensions of the current problem to IDPs, alongside proper methods of preventing spread and managing infections. The consequences of aberrant behaviour on everyone involved should be fully explained to them as well – it is paramount at this time to communicate acceptance to IDPs into their host communities, so that within crises they would think and act constructively as community-members, and not destructively as disgruntled outliers.

- Basic, healthcare and WASH facilities should be provided at this time to IDP Camps across the country as preventive measures, to enable them stem spread within their communities.

With all (sanitized and/or washed) hands on (a properly disinfected) deck, we should, IDPs and non-IDPs alike, prevail in the end.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China