Future Energy Use in the Developing World: Implications for poverty reduction and climate goals

In view of the long-standing debate between green growth and de-growth, this analysis throws light on the dimensions of future energy use growth and its implication for development and climate concerns, in the context of the developing world.

Latest energy demand projections show that a global energy transition is underway. Based on baseline projections by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), BP, Exxon Mobil and IEA, developing countries would have a larger share of energy use. This would be driven by changes in economic growth and structure, demography, and technological advancement. While these projection studies have varying model assumptions, they reach similar conclusions regarding energy use growth between developed and developing countries.

Specifically, projections indicate that global energy use is expected to rise by around one-third by 2040, most of which come from developing countries or non-member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (non-OECD). While energy demand slightly declines in OECD group (total: -0.3%) between 2017 and 2040, it is expected to rise significantly in non-OECD group (total: +56%) within the same period, with non-OECD Asia taking the lead. Thus, by 2040, developing countries will have around 67% of global energy use, up from 57% in 2017. China of course maintains the largest share of energy use. However, the fastest growth by far is expected to occur in India -- and to a lesser extent in Africa & other non-OECD Asia. But the slowest growth will occur in developing Europe & Eurasia, particularly, Russia.

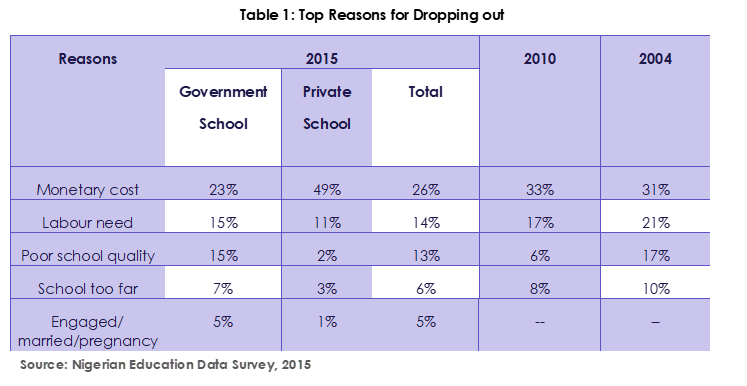

Across sectors, industry will remain the largest contributor to overall growth in energy use for developing countries but will contribute twice as much as commercial, residential and transport sectors combined (figure 1). Strikingly, by 2040, the industrial sector of developing countries is also expected to contribute more energy than all the sectors of developed countries combined (figure 1). A key implication of the relative significance of industrial energy use is that, development efforts which narrowly targets household demand for energy may not be as effective in reducing energy poverty, improving human development, and controlling the climate impact of energy demand.

Data Source: EIA International Energy Outlook (2017)

Why developing countries will consume around 67% of the world's energy by 2040.

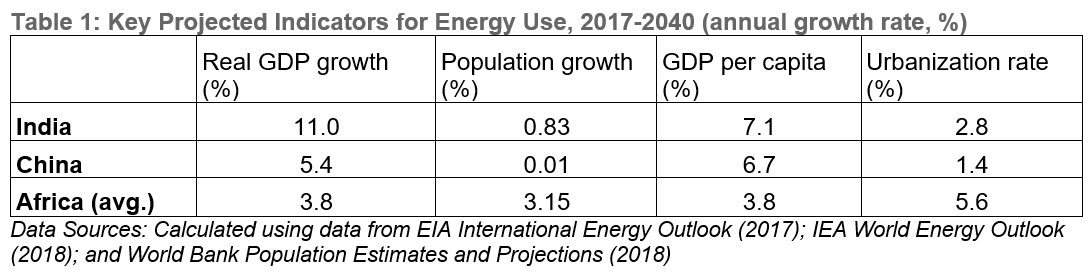

Rising energy use for the biggest users is expected to be driven by economic growth -measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), urbanization, and population growth. For India specifically, energy use growth will be mostly driven by expanding economic output --well above rates in China and the rest of the world. For Africa, energy use growth is expected to be mostly driven by fast growing population and urbanization –fastest rates globally (table 1).

However, for China, its current fast-growing energy use will begin to slow down around 2030s due to slower population growth and increasing transition away from energy-intensive industrial sectors towards less-energy intensive manufacturing and service sectors-- enabling it generate additional economic activity with lower energy use. This transition will be partly driven by stricter industrial standards in light of serious pollution concerns in China. This gives way for India, other developing Asia and Africa to pick up more heavy industrial production for global consumption by 2030s.

The slowest energy use growth for developing countries, however, is expected to come from developing Europe and Eurasia group, especially Russia, largely due to low population and economic growth as well as significant energy efficiency gains.

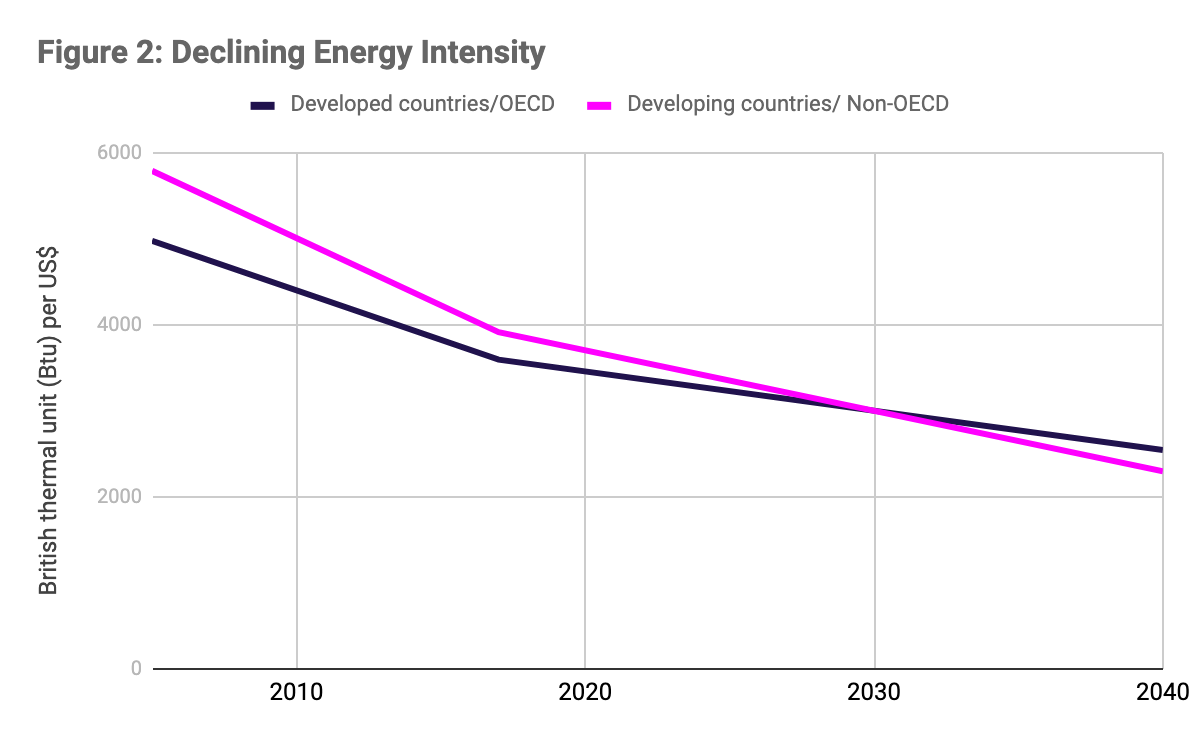

Energy intensity will decline, but not enough to stay on track with climate goals

These energy demand projections also show that while overall energy use increases, global energy intensity (amount of energy used per GDP) will continue to decline in the future --from around 1% p.a. (1950-2015) to around 2% p.a (2015-2040). The decline in energy intensity will be mostly driven by the decoupling of economic growth from energy demand –which is ongoing in many developed countries. This decoupling is reflected in slower economic and population growth as well as shifts in economic structures from lower-skilled manufacturing to higher-skilled advanced manufacturing or services. Interestingly, developing countries are expected to decouple by twice the rate of developed country grouping, on average, from around 2030s (figure 2). This would come mostly from China where environmental concerns and air pollution will force the Chinese government to promote better climate-sensitive industrial policies. Although decoupling occurs at a faster rate in the developing world, overall energy intensity remains high.

However, a 2% reduction in energy intensity is not enough to put the world on the path to meeting climate goals. For such reasons, some authors like Jacobson et al. (2017) suggest pathways for reducing energy use that reflect degrowth, while others propose improvements in energy efficiency as the best solution. But recent studies suggest that the latter may not be a viable long-term solution. Particularly, Fouquet & Person (2011) and Luke et al. (2014) highlight that energy efficiency measures and technologies enable cost declines and expansion of services, which ultimately leads to higher energy use — known as the rebound effect. Therefore, they caution policymakers about depending heavily on efficiency-related emissions reduction as a climate mitigation strategy.

The key implication is that relevant actors in the international community, academia and government still need to think more carefully about other ways to reduce climate impact from energy use, beyond energy efficiency.

Data Sources: Calculated using data from EIA International Energy Outlook (2017); IEA World Energy Outlook (2018); and World Bank Population Estimates and Projections (2018)

Is degrowth, then, a viable alternative solution for limiting energy demand and its impact on our planet? No, due to its impact on development/poverty reduction goals

One of the central messages in these projections is that the level of future energy demand will be largely determined by how fast developing economies grow, and what type of activities make up their economic growth. Given climate change concerns, it seems passively implied that degrowth –limiting the pace of economic growth – could be a viable solution for reducing future energy use. This notion may also be underpinned in the low levels of energy access targets envisioned by many development institutions, like the United Nations (UN) as part of its global development objective – as Moss & Gleave (2013) and Caine, et al. (2014) suggests. However, limiting the use of energy – a resource so essential to human progress – is not an effective alternative, if the world is interested in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs), especially those on poverty and equitable access to energy (SDGs 1 and 7).

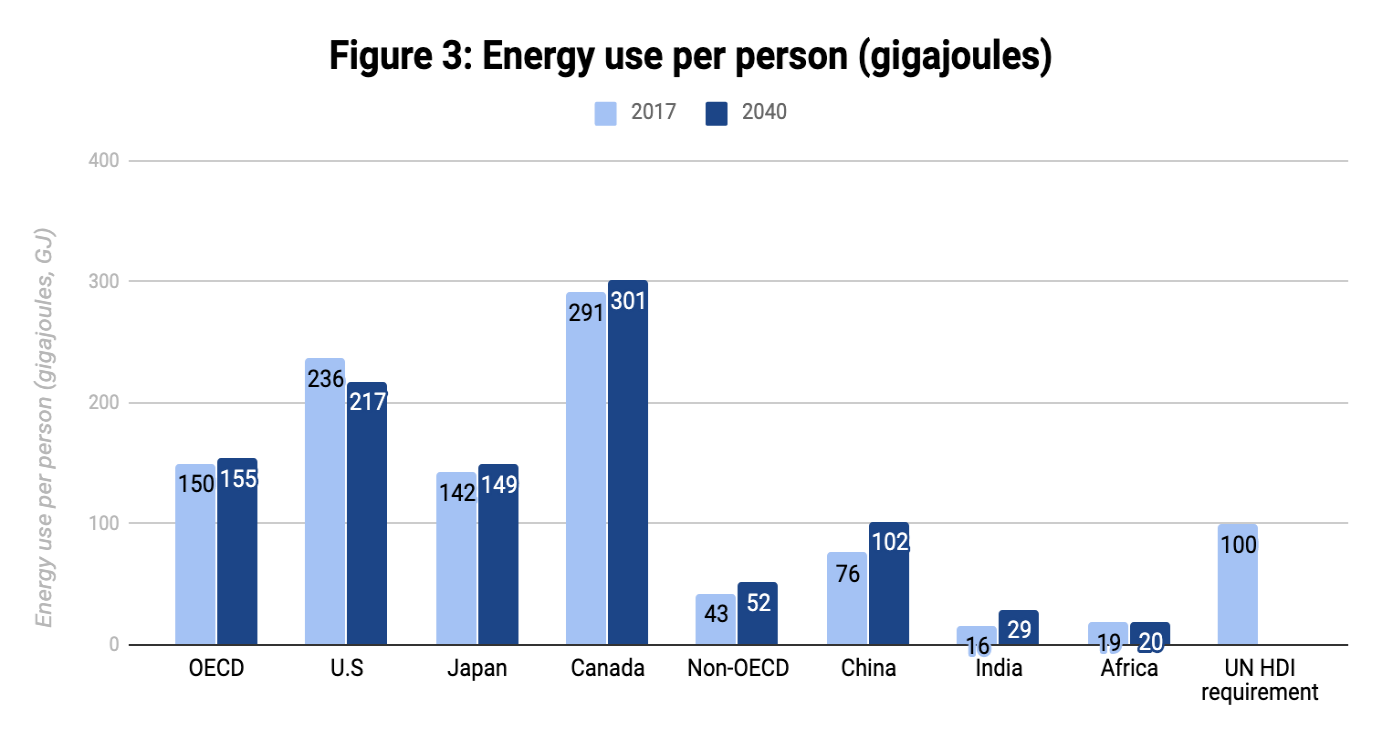

Despite energy demand growth, average energy use in many developing countries will remain below levels required for human development. The UN’s Human Development Index (HDI) suggests that increases in energy consumption up to around 100 gigajoule (GJ) per head are associated with substantial increases in human development and well-being, after which the relationship flattens out. However, many developing countries will not attain this level by 2040 (figure 3), despite fast growing energy use. Specifically, despite economic growth and prosperity of the Indian people, energy use per head increases only marginally by 2040. For Africa, its fast-growing population is expected to suppress the prosperity of its people, thus energy use per capita only rises by one unit to 20 GJ.

But interestingly, energy use per head in China (at 102 GJ) could meet UN standards for human development by 2040. Perhaps this would classify China as a developed country by 2040. It is important to note that, while China struggles environmental degradation due to the high energy use and pollution of its industries, China’s high energy use has also allowed for faster development, that will potentially transform it to a developed country by 2040. This case of China buttresses the environmental cost, yet value of high energy in driving development.

Data Sources: EIA International Energy Outlook (2017) and World Bank Population Estimates and Projections (2018)

Key Takeaways

Environmental and climatic concerns are vital variables for consideration, given its immediate and long-term impact for our world. However, limiting energy demand through degrowth, especially for developing countries, would be inappropriate -- given the need for energy to drive human development and poverty reduction. Therefore, we need to think of a lower carbon and higher energy planet, bearing in mind both climate and socio-economic development goals, especially for developing countries where high energy level is required to lift people out of poverty.

Drawing on my recent grounding in the Ecomodernist ideology at The Breakthrough Institute, Any progress at advancing the twin goal (climate and poverty reduction) will require both: advanced technological innovations and piecemeal incremental policy changes to guide household and especially industry behavior. It would require unusual and equitable energy policy decisions to decrease the climate impact of energy use without reducing consumption, especially for developing countries where high energy is much needed.

The global community and developed countries will need to work with fast developing countries to minimize the environmental footprint of their industries, without minimizing production. Policies that encourage investments in initiatives that reduce emissions from industries, without constraining output, should be prioritized over household energy demand that are often in the forefront of development efforts. Carbon capture and storage for steelmaking, as well as non-emitting ways to produce cement are some good examples.

Lastly, reducing the social and political barriers to a high and clean energy transition will require relevant stakeholders to continuously spread the message of hope and possibilities that will fuel government action and human ingenuity. As advocates of energy equity emphasize, “the way we use energy will become increasingly clean not by limiting consumption but by using expanded access to energy to unleash human ingenuity”.

English

English

Arab

Arab

Deutsch

Deutsch

Português

Português

China

China